Featured image: the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled this past summer on the citizenship question.

By Amelia Davidson

Since the dawn of time, civilizations have counted their members. In a tradition that dates back to the Bible, ruling bodies have conducted censuses to determine the size and scope of the people under their control. But censuses are more than just a measure of population. They determine who counts as a member of a country; who is in and who is out.

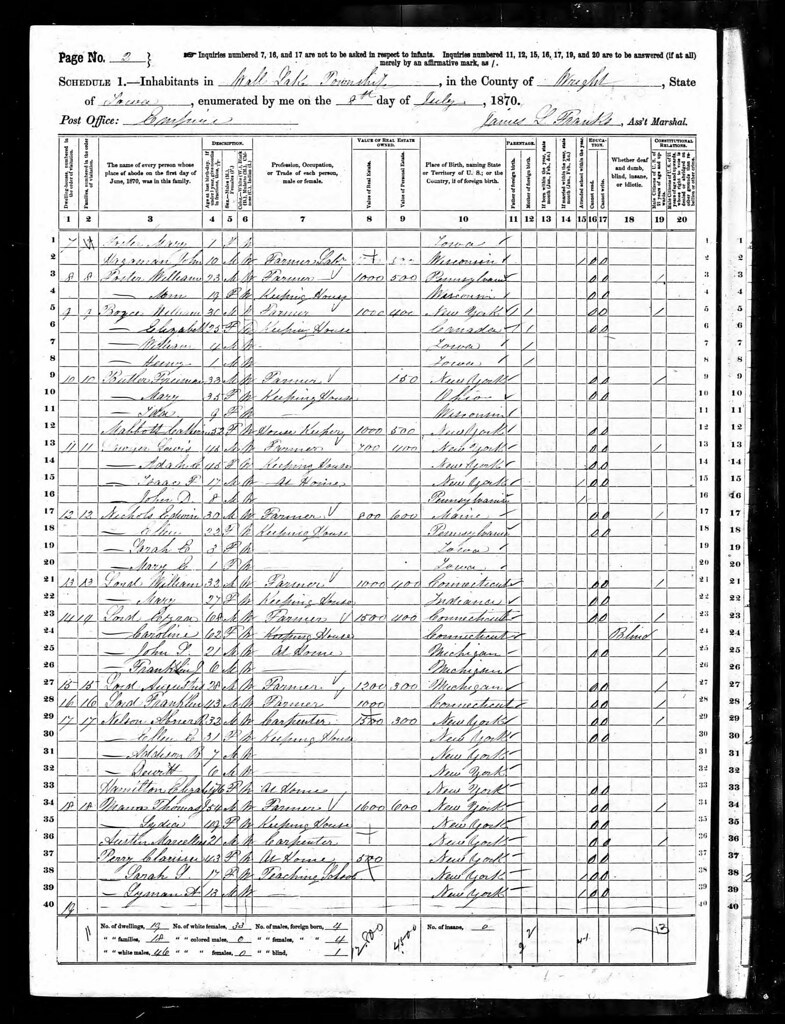

It is no coincidence that Article 1 Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which established the practice of a decennial census, was the same article that determined that all slaves counted as three-fifths of a person. Throughout American history, the census has been used by those in power to establish a standard for who counts as an American. This practice started in 1789, when it was enshrined into law that Native Americans did not count in the population. In the following centuries, fluctuating inclusions and omissions of racial categories in the census made it clear which ethnic groups were wanted in America and which were not. In more modern days, the census has been used by partisan lawmakers to create gerrymandered districts to best serve their political agenda.

Considering this history, the Trump administration’s announcement in March 2018 that it would be reinstating the citizenship question for the 2020 census immediately set off alarm bells. The citizenship question, which asks respondents to report their citizenship status when filling out their census forms, has always existed on the long-form census survey, which is sent out to a very small sample of respondents. But the Trump administration proposed putting the question on the short-form survey that all Americans are asked to fill out, which has not been done since the 1950 census.

To be clear, the citizenship question does not ask about immigration status; rather, it asks whether one is a citizen of the United States or not. This means that no citizenship data from the census could be used to prosecute or deport undocumented immigrants. But that is not experts’ main concern. The issue is that the presence of a citizenship question could dissuade non-citizens and those in predominantly undocumented communities from responding to the census, due to fear that citizenship information could be used against them. The Census Bureau’s own estimates say that with a citizenship question, 5 – 12% of non-citizens would not participate in the census. Testifying in Department of Commerce v. New York—a major lawsuit on the citizenship question—Duke professor and researcher on survey methodology D. Sunshine Hillygus stated that such estimates prove that the question skews the census. She also added that the estimates themselves are “conservative.”

Census data are used for two main purposes: determining each state’s number of seats in the House of Representatives and proportionally giving federal aid to states that can then be used for welfare and social programs. Given that immigrant communities traditionally reside in Democrat-leaning states, if they were undercounted in the 2020 census, it would lead to fewer congressional representatives from blue states and less federal aid going to these states and communities. Knowing this potential consequence, critics of the census immediately claimed that the administration’s policy was not just a continuation of President Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric, but also a calculated effort to lessen Democratic influence in Congress and cut aid to minority communities.

In May 2019, such critics found the hard evidence they had been looking for in the form of leaked memos from the late Thomas Hofeller who, before his death in 2018, had played a significant role in the Trump administration’s decision to include a citizenship question. In his memos to the administration, he specifically cited that a citizenship question would “be advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites” in terms of redistricting. In other words, the citizenship question allowed the census to be used to the advantage of white people in power: a trend eerily reminiscent of historical census laws that elevated white people over black people and Native Americans.

In the spring of 2020, when households around America begin to fill out census forms, they will not encounter a citizenship question. The question died in an alarmingly public fashion this past summer, in an internal saga fit for reality television. After initially facing six lawsuits at the state level, the citizenship question was taken to the Supreme Court, which announced its ruling in June 2019. The court voted 5-4 to block the citizenship question, with Chief Justice John Roberts joining the four liberal justices in a vote that surprised many experts. In Roberts’ explanation of his decision, he said that he voted against the question not because of any moral opposition to the question itself, but because he deemed Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ explanation as to why the question was necessary as “contrived” and not “genuine.”

Back in 2018, Ross had stated that he was adding the question at the request of the Department of Justice, who wanted to use the data to enforce the Voting Rights Act to help ensure that minority voters were not being disenfranchised. However, in the various state lawsuits it was revealed that this reasoning was false, and the Commerce Department had actually asked the Department of Justice to make the request about the Voting Rights Act. This left Ross scrambling during the Supreme Court proceedings for an explanation as to why a citizenship question was necessary.

On July 2, a week after the Supreme Court ruling, the Department of Justice announced that the citizenship question would not be included in the census, and the Department of Commerce said that it had begun printing the forms without the question. A day later, President Trump, in a tweet, called reports that the question was not being included as “fake” and, to the surprise of his staff, insisted that the administration was still putting the question on the census. The Department of Justice attorneys were baffled and told judges that they did not know what was happening in the administration. In response, the administration tried to switch the entire legal team working on the matter, but faced pushback from judges in New York and Maryland. The issue was finally put to rest in mid-July, when the administration officially dropped the question, with Attorney General citing time constraints on the form printing as the primary reason.

Given that the citizenship question will not be present on the 2020 census, it is reasonable to ask why the topic is still being discussed. For one thing, there is still concern that the widespread talk of the citizenship question will dissuade undocumented immigrants from filling out the census, despite the question not actually being present. But another significant implication of the citizenship question fiasco was its indication that there are people still attempting to define “us” versus “they” in the form of determininh who counts and who does not. In other words, the census is still being weaponized by people in power to marginalize those who could potentially keep them out of power. As Saul Roselaar, the legislative advocacy director of Yale’s Every Vote Counts chapter put it, the gerrymandered districts and skewed representation that comes from an inaccurate census mean that “you don’t get competitive elections, so our representatives not only aren’t, but can’t be held accountable.”

In light of efforts by politicians to skew the 2020 census results, it is more important than ever that all people residing in the United States participate in the census. Only then can the census fulfill its stated purpose of “providing current facts and figures about America’s people, places, and economy.” And only then can the borders drawn and the aid apportioned through the census be accurate and fair.

New Haven, being a large immigrant and minority community, is “hard-to-count”—an official designation used by fair census advocacy groups. Additionally, college campuses are some of the most hard-to-count communities in the United States. Students must ensure that they are not being counted twice, on their campuses and at home, and the process for students living on campus is different from that for those living off campus. These factors place college students as some of the most likely to be miscounted in a census.

But we must be counted. No matter if it is due to attempted disenfranchisement, such as in the case of the citizenship question, or just due to logistical difficulties, not being counted in the census is akin to not being included as a member of the country. There is a difference, however small, between residing within the borders of the United States and being counted as a resident of the United States. The census is the intangible equivalent to a physical land border, quantifying and marking who is here. So be counted. Say that you are here, no matter what people have to say about it.

Amelia Davidson is a first-year in Pauli Murray College. She can be contacted at amelia.davidson@yale.edu.