“We like war less and less the more we become attached to peace, and the more it becomes difficult to think of a group of soldiers without individualizing them. When a soldier dies, we want to know his name and his story.”

By Henry Robinson

[divider]

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he etchings are something that the eye could miss, clustered together in a group of 9 at the exhibit’s entrance. Their lines seem to have been drawn hastily in a flurry of sadness, or exhausted laughter. At the center of one of them stands a man pitching forward, vomit (or is it blood?) coming out of his mouth as he struggles to stop himself falling on a pile of corpses. Beneath his mussed-up hair and rolled-back eyes lies a caption, written in an elegant Spanish cursive–“Para eso habeis naceido.”

“This is what you were born for.”

This particular image is the 12th from Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War series, selections from which are currently on display at the Yale Art Gallery. Created between 1810 and 1820 in response to the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, the Disasters is comprised of 80 plates depicting wartime atrocities. Many of them are difficult to look at, both because of how gruesome they are and because there is an eerily ahistorical quality to them–Goya situates his characters in generic landscapes and doesn’t date the etchings, preferring laconic captions that often address the viewers or speak to their gut reactions: “No se puede mirar” (“One can’t look”), “Esto es lo peor!” (“This is the worst!”), “Por que?” (“Why?”).

Douglas Cushing, an Art History Ph.D student at UT Austin who wrote an essay on Goya for the exhibition catalog, sees the Disasters as “essentially modern” works.

When I ask him why the etchings can have such a profound effect on contemporary viewers, he writes that they contain an element of irrationality that resonates with our current perceptions of the world. “If the Enlightenment divided reason from unreason in a way that transformed our thought,” he continues, “we still have not figured out how to live with that schism.”

It seems fitting, then, that war–a pursuit often plagued by unreason–was Goya’s subject. His contributions to European pacifist and war-critical art have been immense and lasting; painters from Manet to Picasso owe a profound debt to the fearlessness with which he addressed taboo subjects. A pair of active British artists, Jake and Dinos Chapman, have even explicitly repurposed images from the Disasters to create shocking critiques of U.S. and U.K. involvement in the Middle East. A 1993 sculpture of theirs (also called The Disasters of War) recreates every one of the etchings as miniature figurines, clumped together in a group that visually highlights our removal–both physical and psychological–from the human consequences of conflict.

Speaking to The Guardian’s Fiachra Gibbons in 2003, Jake Chapman drew a parallel between Napoleon’s desire to “bring enlightenment” to the “backwater” Iberian peninsula and George W. Bush’s desire to export democracy to the Middle East. (The interview, it should be noted, occurred on the occasion of another one of their Goya-inspired exhibits, for which they had drawn puppy and clown masks on every face in an original edition of the Disasters.)

Goya’s works also inspired the 2014 exhibition at Louvre-Lens The Disasters of War, 1800-2014, a show that highlighted “a growing disenchantment with war” among European artists. It placed the etchings center-stage, including 15 of them alongside newsreels from a concentration camp, pictures from Hiroshima and Vietnam, and Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting Napoleon Crossing the Alps.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, an Art History Professor at France’s Sciences Po who curated the exhibition, sees Goya as a watershed. “Before [him], there was practically nothing by way of explicitly negative representations of war and its disasters,” she writes. “But from then on, every artist with an interest [in the effects of war on civilians] referred back–consciously or unconsciously–to Goya.”

“We like war less and less the more we become attached to peace,” Dorléac adds, “and the more it becomes difficult to think of a group of soldiers without individualizing them. When a soldier dies, we want to know his name and his story.”

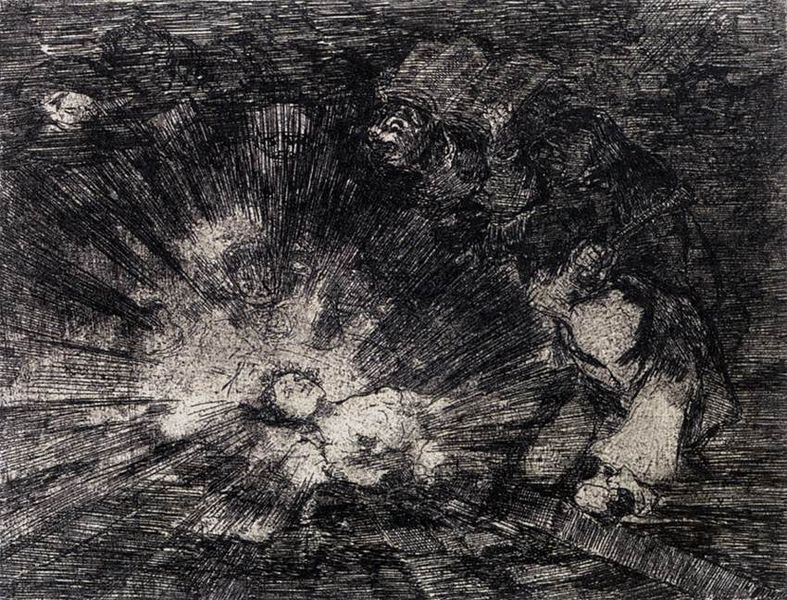

Maybe, then, falling dead and anonymous on a battlefield is not what we’re born for after all. Goya’s etchings can be viewed as an outcry, not just against war in general, but specifically against the devaluation of human life that war can engender–and perhaps no single plate in the Disasters conveys this better than the last one. It depicts a young woman–probably a war casualty–lying dead (or sleeping?) in a brilliant pool of light. Surrounding her, blinded by the glow, is a host of indistinguishable human-animal monstrosities, decked out in the trappings of political and clerical authority–representations of the inhumane forces responsible for so much bloodshed. The caption reads “Si reucitaria?”

“Will she rise again?”

It’s evident that Goya wants her to–or maybe that’s just me.