By Caroline Ho

Read a formatted pdf of the article here.

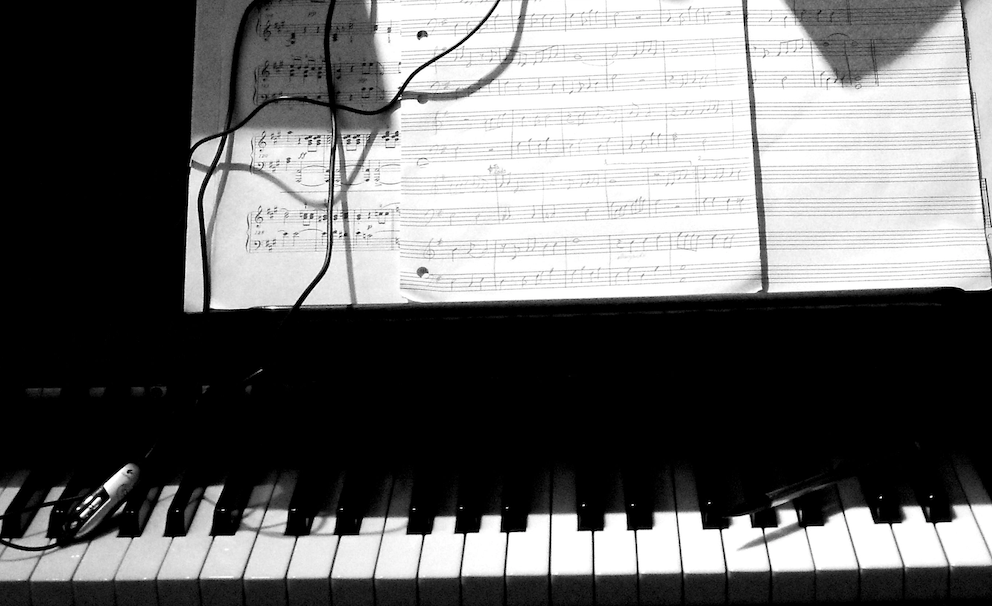

Throughout my childhood, I often sat in a small room in my house for hours on end. Seated at a brown, upright piano, I would practice Mozart and Bach, check-off my rote scale exercises, and when I was done, I’d write my own music. The experience of writing my own music was incredibly special even back then—to hear the rise and fall of melodies, the finality of cadences, and the narrative quality of a tune was to begin to understand music as expression, rather than merely a skill. It was akin to learning a language; I began to understand the natural ebbs and flows of musical “sentences” and phrases and internalize harmonies that I found particularly emotive.

Through the years, writing music has become my retreat and the way I make sense of the world around me. This process is my home—a permanence that helps me cope with the transience of time, people, culture, and place. Yet, my compositional space is not one that I want to hold selfishly, because I recognize that my musical influences have spanned many different cultures and eras. My accessibility to music that is diverse, new, and rich is a blessing that I am thankful for every day.

Even though composing is, in a sense, very personal and ingrained, I describe it as ‘home’ with some hesitation. The compositional process is anything but one of unwavering consistency and predictability. It is rather terrifying, sitting down at a piano and creating something out of nothing, knowing where you are emotionally and trying to convey it through notes on a page. The process is simultaneously technical and emotional. The two aren’t mutually exclusive; specificity need not be over-intellectualized nor emotion entirely impulsive.

Over time, I have learned that less is truly more. Music can be born out of the simplest of ideas: a two-note motif, a descending scale. Harmony colors these ideas—beds of sounds that paint strokes of emotion amidst melody. Most importantly, these ideas arise from my interactions with the places and people around me.

I grew up in Los Angeles, surrounded by the vibrant musical communities throughout the city. Yet, it was not until I left for college that I began to understand the compositional process as creatively healing and immensely personal. Moving across the country was difficult, as I had spent much of my childhood at home practicing, listening, and writing in a very ‘safe’ musical environment. My studies were quite insular in the sense that I didn’t have much musical freedom; rules were learned, foundations set, and the standard repertoire performed. When I left this space, my approach to music naturally began to shift.

I didn’t feel much at home at Yale until I began writing music. At first, the mere fact of physically being in a small practice room in Hendrie Hall, away from the, at times, overstimulating and eager nature of the first semester of the first year, was a quiet solace. Over time, I began writing songs with new friends. I listened to different music. I became obsessed with film scores. My musical past, which had consisted of intense studies of the classical canon—Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, Tchaikovsky—became somewhat passé in my head, even though so much of its influence was and is so deeply ingrained in my innate musical senses. During this time, extending beyond my known confines of music allowed me to open up to the world and immerse myself in everything that this new environment had to offer. Peers who were both musicians and non-musicians influenced me in numerous ways. Their musical journeys were fascinating to me and I was excited to see what moved them, whether it be songwriting, playing in a string quartet, or finding unknown artists to listen to in the depths of Spotify. I was deeply changed by the way that music—in all of its various forms—played a role in our lives and became determined to write music based on my own experiences that could also have such an impact.

Besides being surrounded by a different musical environment, New Haven and Los Angeles are drastically different places. The fluctuation of seasons and weather in New England was both exciting and terrifying. The collective emotional rollercoaster palpable in the student body accompanied the rise and fall of academic strain: fall and spring semesters, finals periods, shopping weeks. During these times, the compositional process felt most vulnerable. I feared the process because I knew there was only one path to artistic authenticity: emotional honesty, which can be a very giving process. Periods when I did not compose were unmemorable, as if the capricious waves of new experiences and emotions rushed past me too quickly to process them. I spent a lot of time improvising and allowing myself to feel unrestricted, untethered to finality or product.

Composing is not a finalized workflow, which I was often reminded of, to my frustration. But it reflects so much of my interactions with my surroundings. Some of the best music I’ve written has been in places unfamiliar and unexplored, places that pushed me to find meaning and inspiration in the rawness of their novelty. The summer after my first year, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to study abroad in Italy—a country rich in classical music, from the origin of the opera to the plethora of summer classical music festivals. I spent much of my free time at a piano in my host family’s home. Despite the country’s beautiful landscapes and the generosity of the people I met there, I felt incredibly displaced. I was homesick, and a bad injury had left me with crutches and hospital visits for the summer. I missed my family and simple comforts such as playing jazz with my dad or eating my mom’s home cooked food. Writing music at the piano that summer allowed me to process the displacement I felt, the fact that despite my best efforts at learning the language and history, I was still a foreigner in a temporary home. That summer, I wrote a piece for solo piano, titled il tempo che vorremmo, translating to “the time we would like.” Its concept arose from the notion that time with people—especially those we cherish—is passing, and increasingly so as we get older and navigate new experiences without them. I am inclined to believe we are always yearning for a home base: people and places rooted in comfort and dependability, even as passing time makes it easier and easier to seamlessly waft away from home.

I consider this piece to be a pivotal point in my musical journey, as it solidified what the compositional process really meant to me—a creatively healing medium that emotionally memorializes the passing of time and experiences. When I returned to college after that summer, I can’t count how many times going to a practice room to sit down at a piano and write saved me, in the way that a parachute catches a person falling through nebulous air. Sometimes the moment I closed the door, I’d call my mom and heave a sigh of relief. I’d often stop and take a moment to just breathe, knowing that the ability to write music was the ability to be completely and utterly myself, free of external vices and pressures, and to understand the world around me in a space that I could call my own.

At the same time, I have to sift through all the noise and find the bits that mean something, the strands of notes that say something and exist beyond simply sounding pleasant. I’m often reminded of a professor who told me that I shouldn’t want people to describe my music as simply pretty. For every one hundred ideas, there may be only one idea that develops into something more.

And sometimes, I want my art to be as is…fragments of phrases and notes tossed aside two too many times, melodies left unheard outside of the confines of my own mind.

Writing music allows me to create space entirely grounded in my existence, wherever or whenever. Many artists try to find home within their work; displacement, discomfort, and distance feed the innate desire to feel whole. But writing music is dynamic, just like our experiences across different places and times. It is how this process becomes recognizable and personal where we begin to see how it becomes more than just notes and melodies—it is home itself.

Caroline Ho is a junior in Timothy Dwight College. You can contact her at caroline.ho@yale.edu.