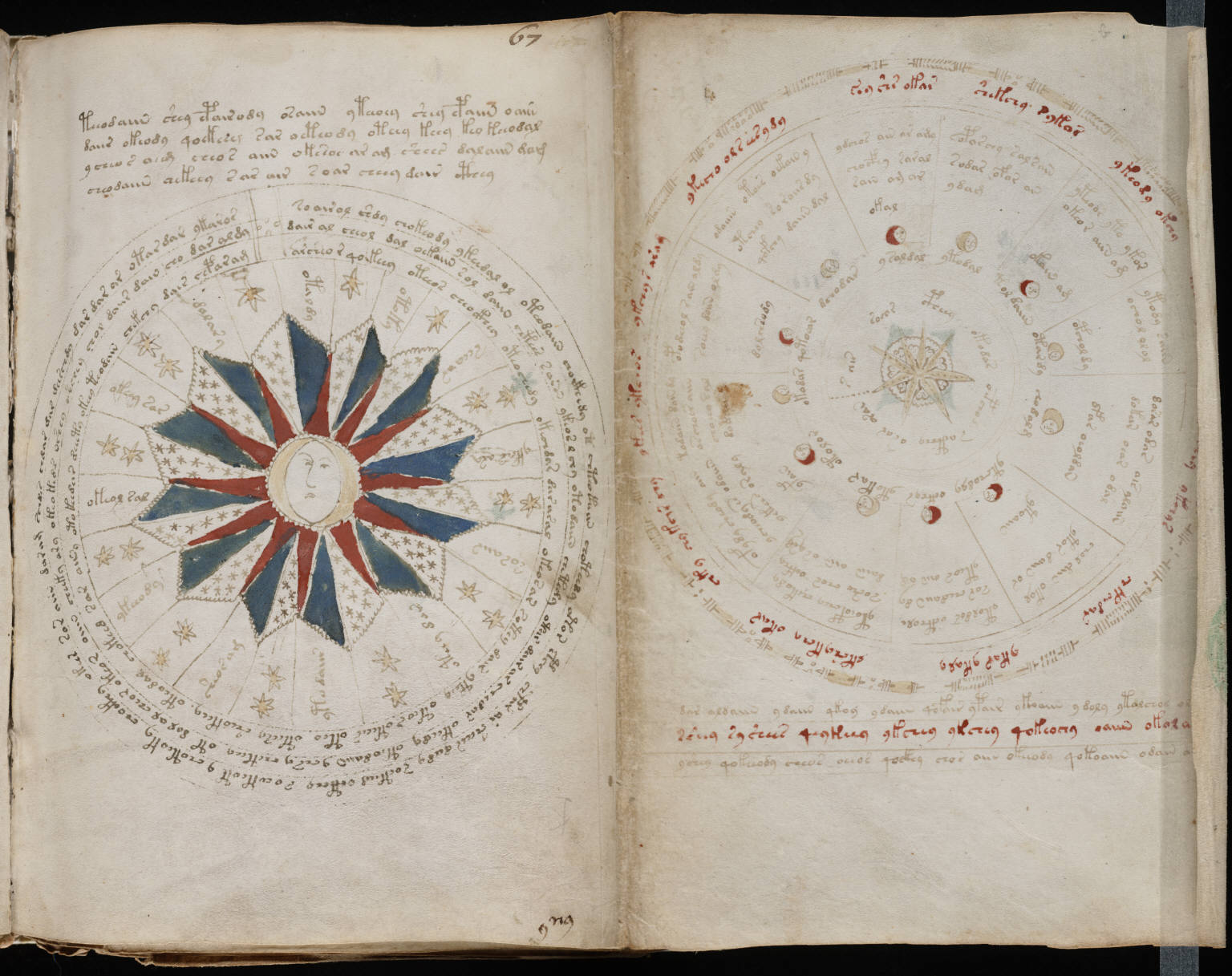

Astrological charts depicted in the Voynich Manuscript.

[hr]

By Alma Bitran

[divider]

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n a small, discolored sheet of parchment, a blue flower dances. Its roots snake down like tentacles, curly-edged petals outstretched. Brown borders rein in scribbled patches of green; the artist has taken great care not to color outside the lines. The hundreds of tiny petals around the flower’s head are rendered so painstakingly, so imperfectly, that they’re almost cute. You could mistake this page for a fourth-grader’s botany homework; the illegible script at the top of the page only convinces you further. But this is not the work of a child — rather, it is one of the most coveted volumes in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. This text, known as the Voynich Manuscript, has enthralled — even obsessed — scholars and laypeople alike for hundreds of years. But why?

This fifteenth-century manuscript’s allure seems to lie not in its meaning, but in its lack thereof. Written in an unknown script dubbed “Voynichese,” nobody, not even the most accomplished cryptographers and the most powerful supercomputers, has succeeded in cracking its cipher. The work’s mystery isn’t limited to its text — not a single one of the plants illustrated has been successfully identified by botanists. The work’s imagery, which also includes astrological charts and cryptic drawings of women bathing naked, does not conform to the visual language of medieval alchemic texts. Jennifer M. Rampling, Assistant Professor of History at Princeton University, writes in an essay, “The absence of context means not only that we cannot read its images, but that we cannot know even that the images were intended to be read.” This is a work of literature that stubbornly and systematically refuses to be understood. If language serves to convey meaning, the Voynich seems to defy the very purpose of the written word.

Perhaps for this very reason, the Voynich has captured the public imagination in a fashion unparalleled among medieval manuscripts. The work has inspired comic books, video games, novels from authors as notable as Lev Grossman, and even a symphony by Yale School of Music professor Hannah Lash. Internet forums burst with fan theories about the Voynich, ranging from the plausible (for instance, that the text is a guide to women’s health), to the absurd (which often include aliens). Voynich enthusiasts flood the inboxes and phone of the Beinecke’s Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts.

[divider]

A closeup of one of the Voynich’s depictions of bathing women, common throughout the manuscript.

[divider]

With so much intrigue surrounding the text — scholarly and popular alike — one would expect its mysteries to have been solved by now. But this is hardly the case. I spoke with the Executive Director of the Medieval Academy of America, Dr. Lisa Fagin Davis. Davis completed her PhD in Medieval Studies at Yale, during which she first became acquainted with the manuscript, which she calls “a delicious mystery.” She explained, “Maybe someone has a theory about the plants; someone has a theory about the linguistics. But no one as yet has ever put together a grand unified theory of Voynich that accounts for all the different components and how they work together — and that accounts for what we know for a fact about the manuscript, scientifically. And that’s really what we’re waiting for.”

But to believe in some sort of Voynich holy grail — a theory of everything — implies that it even has a meaning in the first place. What if the Voynich Manuscript is so mystifying precisely because it means nothing at all?

According to Dr. Claire Bowern, Professor of Linguistics at Yale and Voynich expert, this is highly unlikely. In an email, she wrote, “The statistical features of the words and letters [in the Voynich Manuscript] do point to a natural language rather than gibberish.” Natural languages have certain statistical regularities — for example, the prevalence of letters in certain fixed locations within words. The Voynich checks these boxes, suggesting that the search for meaning in the manuscript is not a futile one. Davis concurs, thinking it likely that Voynichese is “a real language — a natural, human language — not a made-up language like Klingon or Elvish.”

But even if we did manage to someday decode the Voynich, would we find anything significant? According to Dr. Bowern, “we sort of know what’s in most of the book. The first part is a herbal [a guide about various types of plants]; there’s a part about astronomy; there’s a bit that’s probably about poisons; it’s possibly some sort of medical alchemical compilation.” But a medieval “scientific compendium,” as Davis calls it, hardly seems to be the true object of the Voynich obsession. Towards the end of our phone call, I asked her: does she even want to know what this manuscript says?

“Ha! That’s a really great question.” She paused for a moment. “I’m not sure that we will ever find a solution where everyone on the planet agrees, yes, it’s now done, the problem has been solved, the Voynich has been decoded and everyone is happy and accepts this. And I can promise you that the Beinecke Library will never publicly endorse one solution over another. Their policy is: no comment, always. And so I think that the work will always go on. Even if a solution is published that everyone can test and reproduce and agree upon, there will always be people who think it’s wrong for whatever reason. I’m not sure there will ever be a last word.”

[divider]

A page from the herbal section of the Voynich Manuscript.

[divider]

Perhaps even more extraordinary than the human instinct to look for meaning where there is none, is the instinct to is look for meaning and all the while secretly hope we’ll never find it. We relish the Voynich Manuscript for its “delicious mystery” — for its reminder that the path from language to meaning is not always a straightforward one. Perhaps we’ll someday crack the Voynich cipher. But until then, cryptographers, art historians, linguists, paleographers, scientists, medical historians, and internet conspiracy theorists have a common call to arms. The Voynich Manuscript is a site for collective meaning-making. It can be forgiven, then, if some hidden part of us hopes the search will never end.

[hr]

Alma Bitran is a sophomore majoring in humanities in Grace Hopper College. You can contact her at alma.bitran@yale.edu.