BY ANGELICA CALABRESE

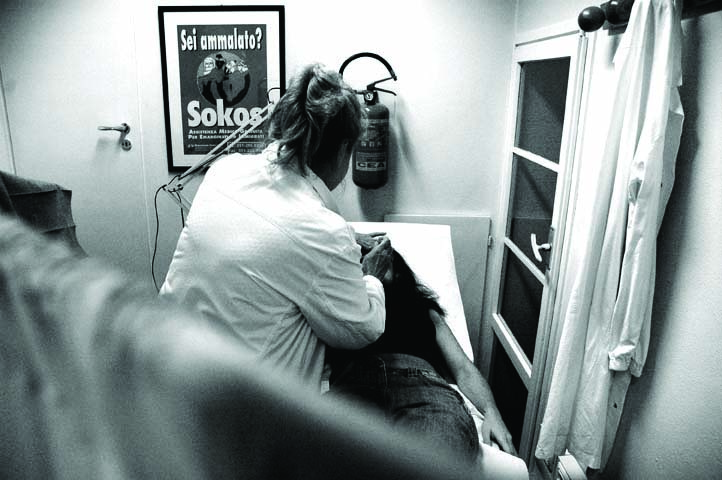

On the table between us lies a small photo ID of a five-year-old boy, blonde and smiling. We’re sitting at the reception desk of the Sokos Center, a volunteer-run health clinic in Bologna, Italy, dedicated to serving the city’s undocumented immigrant population, and Boris is here to apply for his son’s health card. Rosanna, the secretary that I’ve been volunteering with during my semester abroad, peers over her glasses at the photo: “Oh, what a handsome little guy. Does he go to preschool?”

“No,” replies Boris, who shares his son’s blonde hair and blue eyes. “He doesn’t go to preschool.” As Romanian citizens, Boris and his son are guaranteed freedom of movement to any EU member state, but not much else. To access Italian social services, Boris must enroll in the civil registry, which he cannot do without a job. Boris hopes to enroll in the registry soon, but first, he needs a formal work contract from his employer, for whom he works unofficially as a blacksmith. “He keeps telling me he’ll give me the contract,” Boris tells us, shaking his head, “but he still hasn’t given me anything.”

In theory, their EU citizenship should ensure Boris and his son a health card and therefore access to care regardless of Boris’ employment status, but in practice, the system for “unregistered” EU citizens like Boris and his son fosters discrimination and exclusion. Yet Boris and his son have a paradoxical advantage: Both were born in Moldova, a small non- EU country sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine that formed after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and both have dual Romanian and Moldovan citizenship.

Although their Romanian citizenship made it possible for Boris and his son to get to Italy, it now stands in their way. The health costs of unemployed EU citizens who are unable to enroll in the registry should be covered by their home country’s social security program. The E.N.I. card (Europeo Non-Iscritto, or Unregistered European), allows them to be treated by regular Italian physicians, relying on reimbursement of medical spending by the home country. This reimbursement system works for immigrants from wealthier European countries such as France or Germany, but Italian doctors rarely accept an E.N.I. card presented by a Bulgarian or Romanian, assuming that the reimbursements will not arrive due to the corruption and incompetence of their home health care systems. Thus, many Romanians and Bulgarians are left without care.

Unemployed non-EU members, on the other hand—such as Moldovans—can apply for the S.T.P. (Straniero Temporaneamente Presente, or Temporarily Present Foreigner) card. Each region addresses the needs of patients with S.T.P. health cards differently, and in Bologna, these needs are met through Sokos, and other similar medical volunteer organizations, which offer both general care and specialized care such as gynecology and psychiatry.

Patients with the E.N.I. card, however, are not supposed to be treated at Sokos. But sometimes, there is nowhere else to go. The volunteers at Sokos offer more than just healthcare: They also help people like Boris put together the documents necessary to apply for their health cards, providing many immigrants with the only document that attests to their presence in the city. “We are the only ones that acknowledge them,” pointed out Dr. Natalia Ciccarelli, the Center’s Health Director.

Rosanna calls over Dr. Ciccarelli to discuss Boris and his son’s situation, and the two women consult Boris from across the desk. Although it would have been more advantageous for both Boris and his son to use their Moldovan identity to apply for the S.T.P. card, Boris had already acquired an E.N.I. card at another center. If father and son have cards associated with different citizenship and different legal residences, they may run into problems with the government. So Rosanna applies for the E.N.I. card for Boris’ son, knowing that although it will attest to his presence in Bologna, it will likely not ensure healthcare. She tells Boris to come back and apply for the S.T.P. card as soon as his current card expires.

The current system, bureaucratically complex and circuitous, clearly yet insidiously discriminates against Romanians. Only a fortunate few have the ability to negotiate between identities, sometimes presenting themselves as Romanian, sometimes Moldovan, for better care. Encouraging white lies and hidden identities, the system puts the most vulnerable at even greater risk.

Angelica Calabrese ‘14 is in Morse College. Contact her at angelica.calabrese@yale.edu.