BY STEPHANIE SIOW:

“I was in the protest,” said Kasidet Manakongtreecheep ’17. “We achieved our goal – we took over government buildings and roads and even the Democracy Monument. We created mayhem.”

Kasidet was one of tens of thousands of protestors who, for more than two months, have taken to the streets of Bangkok and shut down government buildings. The movement, led by opposition leader Suthep Thaugsuban, aims to force existing Prime Minister Yingluck Shinwatra’s government to step down in favor of an unelected “People’s Council” that will reform the political system.

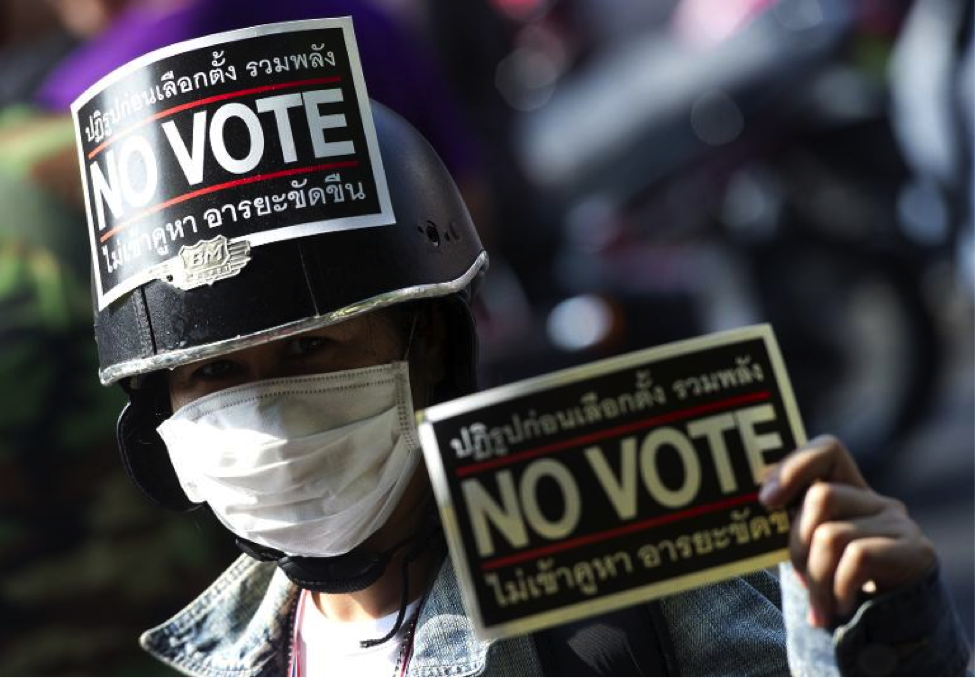

Controversial snap elections in early February failed to resolve the crisis. They were severely disrupted by protestors, who prevented people from entering polling stations. This prompted officials to cancel the elections in parts of Bangkok and nine provinces, leaving the country in political limbo.

A host of underlying reasons has led to the present brawl. The opposition alleges that Ms Yingluck’s “shadow” government, controlled by her brother (exiled ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra), bought rural votes in the kingdom’s north and northeast through economically unsound schemes that have been devastating to the economy.

They may not be wrong. The populist policy in question is a rice-buying program that has guaranteed rice farmers a price 40% above the global market rate for the past two years. True to basic economics, not only has the subsidy encouraged corruption, but it has also wasted taxpayers’ money and left the country in a debt of over US $4 billion in its first year and an immense quantity of unsold stock. The kingdom is no longer the world’s top exporter of rice.

For the past week, hundreds of farmers from Thailand’s southwestern provinces went to the Commerce Ministry to demand payment for the rice they sold to the state – payments that have been delayed for months.

Concerns surrounding the rice scheme grew this week after the commerce ministry announced that China had cancelled an order of more than one million tons of rice. This happened after the National Anti-Corruption Commission announced graft charges against several officials in prior rice sales between Chinese firms and the Thai government.

The question remains: what, then? From an outsider’s perspective, it is unlikely that the government can and will be able to find a quick remedy to the troubled political climate. Yingluck seems to have run out of cards to play. Without credit from commercial banks due to legal concerns and resistance from employees and unions, the Finance Ministry will continue to be unable to pay farmers.

Clearly, the record stockpiles of rice need to be sold to generate cash to pay to the farmers. The biggest challenge surrounding this is the surge in global supply, which means that the rice will probably be sold at a loss. The Thai Rice Exporters Association has said that selling the grain may take five years. Thus, a new parliament needs to convene, to borrow to fund rice purchases, or some sort of scheme needs to be in place to reduce the suffering of the farmers who suffered from the unfortunate outcomes of the scheme.

Second, the policy needs to be reformed, for its economic unviability will continue to plague Thailand’s budget for an inordinate length of time. This can be done only if a parliament is formed, of course, but changing the scheme has to be a priority for either party.

Consequently, competitive elections and their results need to be heeded by both sides. The mass resignation of Democrat MPs last December pressured Yingluck to dissolve the parliament and call for a general election, which they later boycotted. The low turnout at last Sunday’s election resulted in an inconclusive political outcomes; the country continues to be embroiled in political unrest. Both blocs need to take subsequent elections seriously, to avoid a severe waste of resources and time and be able to move forward.

Indeed, some form of authority needs to carry out the electoral and economic reforms. If the opposition continues to demand for a “People’s Council” to reform the system, it needs to provide more details about how the Council will be selected, its constitutional powers and its overall aims. Instead of acting as a panacea to the deep political divides, it is unlikely to pacify both sides.

With no alternatives in sight, Kasidet proposes that ideal alternative would be to “dissolve and ban both parties,” thus allowing a “third party or the monarchy” to rule. The responsibility for the failure to reach consensus lies with both blocs, but the showdown between Yingluck and Suthep’s parties has gotten nowhere. Without the ability to conduct competitive and constitutional elections, Yingluck will remain unable to reassert her mandate, or resolve the ongoing conflict. Only time will tell if the anti-government movement will gain momentum and end the ongoing political stalemate.

Stephanie Siow ’17 is in Pierson College. Her beat is on events in Southeast Asia. Contact her at stephanie.siowsulyn@yale.edu.