Discussing rape and sexual assault with human rights activist Catherine Jane Fisher

By Marina Yoshimura

[divider]

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]any countries downplay rape and sexual assault. In Japan, the media often replaces the terms “rape” and “sexual assault” with “an act of indecency.” However, human rights activist Catherine Jane Fisher changed the status quo when she reportedly became the first woman to publicly speak out against sexual violence to a crowd of over 6,000 people who had gathered in a rally in Japan opposing rape. On February 26, 2018 as part of the Yale Globalist’s Speaker Series, Fisher explained to a group of students at Yale College how she had summoned the courage to fight against the U.S. and Japanese governments to advocate for rape prevention amidst personal trauma, and the significance of her fight for current and future generations.

Fisher began her talk with a brief but explicit account of the day she was raped before discussing her lawsuit against the Japanese and U.S. governments. She had been raped by U.S. serviceman Bloke Deans at the Yokosuka Air Base just outside of Tokyo in 2002. Many Japanese citizens had been opposed to the presence of military bases because aircrafts— some of which crashed into houses and a university— would hover around their homes. Although both governments attempted to suppress her case to avoid further contention, Fisher’s resilience prevailed. She won her court case in 2004, when the Japanese civil court decided to grant her 3 million yen (about U.S. $28,230) as a compensation for physical harm. She accepted only one U.S. dollar. This is believed to be the first time that the United States government endorsed a Japanese court ruling for rape for just a dollar.

Those who are raped are not at fault. Fisher showed students the same outfit that she had been wearing when she was raped outside the military base almost two decades ago to demonstrate that it is never about what a victim may wearing. It was not revealing. “A victim is never to blame for someone else’s heinous acts,” she said. Third parties can also indirectly support the perpetrator by demeaning the rape victim. Fisher said local Japanese police officers asked her to simulate the rape and look for the perpetrator. “I felt as though I were alone,” the former actress and model recalled.

Fisher recalls that when she was raped she thought that she was the only rape victim in Japan. Through Fisher’s extensive research, however, she found that there were many others who had also been raped and silenced. She obtained records of the rape crimes by U.S. military since the early 1940’s and began an awareness project by writing the rape and murder cases on white bed sheets. The white symbolizes the innocence of the victims, and the sheets represent her questioning to both governments as to how could they sleep at night full knowing the widespread cases of rape, and the invisibility of victims’ trauma in the justice system.

Fisher passed around this sheet with the dates and circumstances of those who had been raped by U.S. servicemen in Japan, which extended around the couches in the common room. There were endless cases, but few, if any, were reported. “A girl was raped, murdered, then thrown in the trash,” she explained. “So many cases go unnoticed in Japan. I realized that I needed to fight not just for myself but for others who have suffered at the hands of rapists,” she added. She was fighting not just for herself but also for those whose voices fell on deaf ears. Fisher confronted her past by continuing to search for the man who had raped her. She worked with pro-bono law firm Perkins Coie, which demonstrated their support. She subsequently entrusted her faith in the U.S. law firm, which helped her win her case.

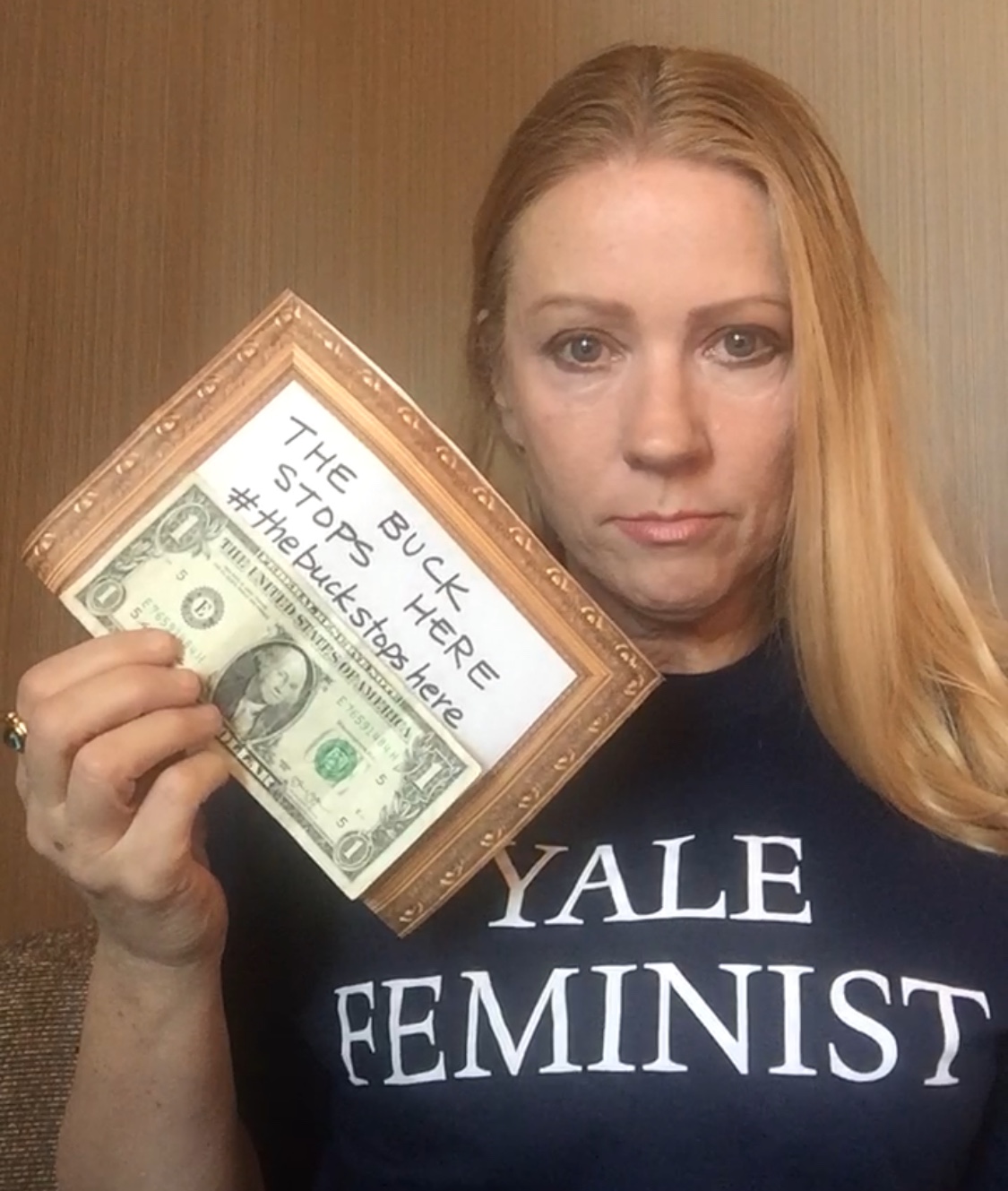

Overcoming trauma from rape is not the same as reliving it. It was easy to assume that after all of what she had experienced, Fisher would call herself a rape victim. After all, authorities had not always been trustworthy or helpful, and she had received almost no recognition or support after she sought support from the police and the governments. As she shared her experience, she paused, then went on to say, “No one protected me. I had to protect myself,” but refused to use the word “victim.” She instead used the term “rape survivor” to remind her audience that her inner strength and perseverance helped her recover and, ultimately, to her empowerment. “My work is called the ‘empowertarian’ work,” she said. She asked the students present at her talk to pass around a one-dollar note she had in her hand. As the dollar was circulating the room, Fisher noted that in English, this process was called “passing the buck.” When the dollar made its way around the room and landed back in Fisher’s hands, Fisher said, “If I may quote President Harry Truman’s words, ‘The buck stops here.’ From this day forward may rape be eradicated at Yale. This is my dream as I am sure it is for all of us here today. May we make this a reality from this day forth.”

Fisher’s case illuminates how, all too often, governments place politically expedient decisions above human rights. However, as is the case with many issues, there are solutions. She suggests that the Japanese and U.S. governments revise the Status Of Forces Agreement (SOFA), an agreement between the two governments regarding the U.S. Armed Forces to uphold mutual cooperation and security in both countries. She specifically refers to Article 16, which states the following:

“It is the duty of members of the United States armed forces, the civilian component, and their dependents to respect the law of Japan and to abstain from any activity inconsistent with the spirit of this Agreement, and, in particular from any political activity in Japan.”

Fisher finds this agreement problematic. “The Status Of Forces Agreement SOFA, between Japan and the US military doesn’t tell you to ‘obey’ it; it only tells you to ‘respect’ it. How do we interpret the word respect?” Fisher asked. She said she hoped to revise the Japanese policy on rape victims and perpetrators and to change one simple word in the SOFA, from “respect” to “obey” to clarify the definitions of the terms and to ensure accountability.

For the current generation, Fisher’s message is a reminder that working towards correcting a collective mindset and language towards rape culture is both necessary and possible. It can start on college campuses. She has left her artwork at the Women’s Center at Yale as a symbol of her commitment to listening to those who have been raped or sexually assaulted. Her story proves that just because something happened in the past does not mean it needs to continue into the future. This generation can shape what is ahead, starting from small steps such as by watching out for others’ safety and one’s own, and by also believing in larger, more sustained changes in legislation and policy. “It’s not about me,” Fisher said. “It’s about you.”

[hr]

Marina Yoshimura is a visiting student from Japan. You can contact her at marina.yoshimura