The American Phenomenon of Rightlessness at Guantánamo Bay

By David Stevens

[divider]

Professor A. Naomi Paik of the University of Illinois came to the MacMillan Center at Yale on Monday to discuss her latest book, Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in U.S. Prison Camps Since World War II, specifically documenting the gruesome experiences of enemy combatants detained at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the legally ambiguous prison camp that has operated outside the bounds of the Geneva Convention and the U.S. Constitution since the War on Terror began over 15 years ago. Paik, who received her Ph.D. in American Studies from Yale, argued that the rightlessness of Guantánamo detainees is a natural product of a society that holds up the liberal values of freedom, justice, and due process.

Paik’s book places the abuses of Guantánamo Bay in a broader historical context, citing the examples of Japanese Americans during World War II and HIV-positive Haitian citizens who were detained at Guantánamo after a military coup in 1991 left them as refugees. The similarity between these three phenomena shows that Guantánamo is therefore not a unique abridgment of American ideals but rather, “as integral to the United States as its professed dedication to liberty and rights.”

The persons caught in this ethical purgatory, Professor Paik argued, are defined by their rightlessness, a “multivalent concept” that results from the dispossession of fundamental rights such as habeus corpus and due process under the law. “The idea of inalienable rights is a fiction.” Citing political theorist Hannah Arendt, Paik noted that these detainees have lost the fundamental “right to have rights,” i.e., the right to live in a political community. The prison camp is the physical manifestation of this dilemma.

The Unites States conception of itself is inextricably linked with the worship of core values, being freedom, justice, and the sanctity of life. Paik theorized that this ideology of American Exceptionalism actually makes possible the human rights violations committed by the United States on behalf of the American cause: if the state carries out this program, it must be just. She furthered her point with the idea that the direct relationship at times present between racism and nationalism engenders the divide between the rightful and the rightless; in other words, any system of justice determines not just who becomes a prisoner, but also who the prisoner becomes.

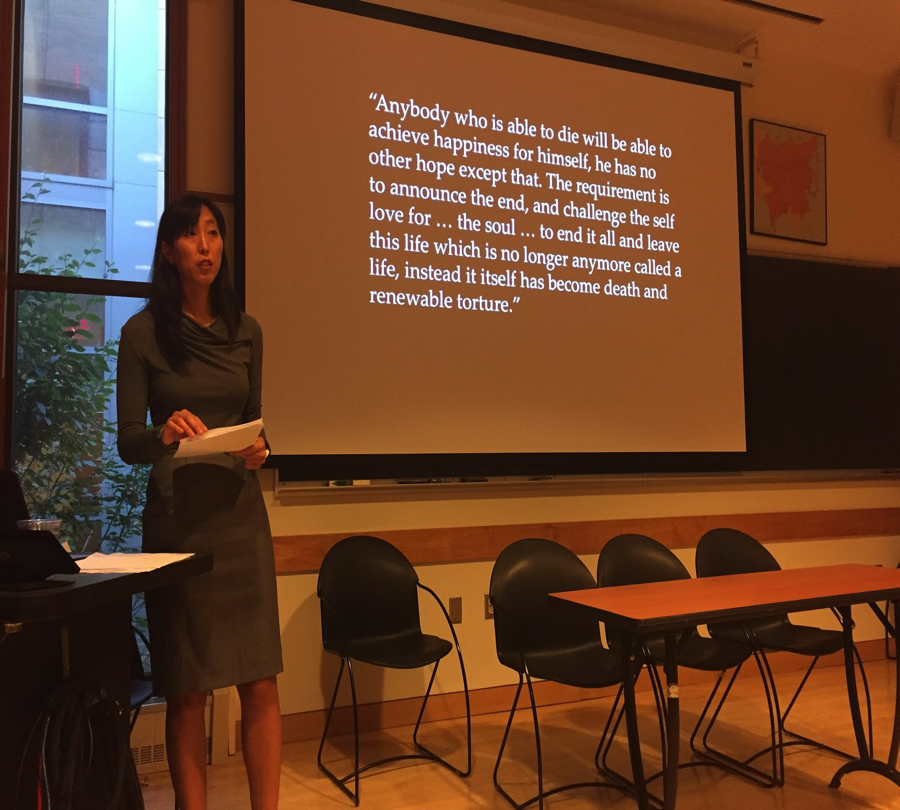

Professor Paik went on to support her theoretical argument with explicit examples from the “counter-archive of struggle” at Guantánamo, mainly hunger strikes, force-feeding, and personal testimonials. The phenomenon of the hunger strike existed at Guantánamo since its first year of operation. In the legally ambiguous limbo of the prison camp, suspected enemy combatants who have been indefinitely contained must resort to using their bodies to communicate injustice to the world. As a response to frequent hunger strikes at Guantánamo, force-feeding was first authorized in 2005. A standard operating procedure from 2013 details how guards should shackle inmates into a special “emergency restraint chair,” insert a food tube through the nasal cavity, and take inmates to a “dry cell” after the force-feeding where they are not allowed to induce vomiting. The reality of the procedure is an even more grotesque event.

“Hunger strikes assert the impossibility of living in this death world,” Paik declared. They are an act of solidarity among the detainees, illustrated by the evolution of S.O.P.s to explicitly prioritize crushing solidarity among inmates by performing force-feeding in private rooms, instead of on open medical wards in groups. The detainees of Guantánamo use hunger strikes and suicide to retain the only modicum of self-expression available to them. As Michel Foucault wrote, “death now becomes … the moment when the individual escapes all power.”

Professor Paik finally discussed Guantánamo Bay as a “theater of security” and criticized President Obama’s pledge to close down the maligned prison camp. When it first opened during the invasion of Afghanistan, Guantánamo was upheld as an example of American military justice: it was what we do to our enemies in a post-9/11 world. While grotesque, Paik believes that simply closing it down would fail to address the endemic qualities that allows it to exist. One doesn’t need to be in an isolated “camp” to experience rightlessness, she argued, and closing the military’s most notorious detention camp would only bring its practices into the standard spaces of American justice, blurring the already frayed border between the exceptional and the accepted.

[hr]

David Stevens is a sophomore in Berkeley who blogs for World at Yale. You can contact him at david.l.stevens@yale.edu