By Rudi-Ann Miller

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta’s campaign platform during the 2013 election cycle pledged to combat systemic corruption and the threat of al-Shabaab’s terrorism. The reputed beacon of hope for East Africa, Kenya has maintained relative control over al-Shabaab, a Somali-based, al-Qaeda-linked group founded in 2006. But in the last three years, corruption, the soft-underbelly of the state, has weakened its security force’s ability to counteract the upsurge in terror activities. However, can the administration really make good on their promises to fight corruption and achieve security?

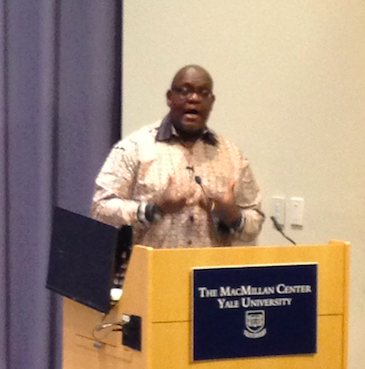

John Githongo, this year’s Coca-Cola World Fund lecturer, has witnessed Kenya misplace its hope in leaders before. Mr. Githongo, in his talk entitled “Corruption, Security and Development: Volatile Nexus,” spoke to a captivated audience in Luce Auditorium on Wednesday, February 11th about how corruption in the country’s elite has permeated to institutions like the security apparatus. Githongo is currently the CEO of Inuka Ni Sisi, an NGO that works for citizen empowerment and good governance.

Githongo made a name for himself as Kenya’s most prominent anti-corruption activist, serving as founder-Executive Director of the Kenyan chapter of Transparency International. From 2003-2004 he was the Permanent Secretary for Governance and Ethics in the administration of Kenya’s president Mwai Kibaki, who had also campaigned on an anti-corruption objective. Kenyans and international observers believed Kibaki was their opportunity to finally achieve full democracy—until John Githongo exposed corruption within the administration that appointed him. A network of “politicians, bureaucrats, briefcase businessmen and military and intelligence personnel” were complicit in scams that siphoned off $600 million in funds that were supposed to advance the nation’s security infrastructure. Rather than catalyzing reform, Githongo’s efforts were labeled as treasonous and he was exiled to Britain for four years.

However, Githongo asserts that corruption is a thorn in the side of the world, not just Kenya. He believes the Western economic model of development has delivered growth but also inequality, which enhances identity politics and breeds corruption in all parts of the world. “Western NGOs are quick to say ‘You must fry the big fish. Until you fry the big fish you are not fighting corruption,’” he says, “but it’s difficult to fry the big fish here [the United States] as well.” Githongo highlights the 2008 Financial Crisis, the result of criminality in the banking system for which few have been held accountable. “Corruption exists everywhere but it’s good because we can look each other in the face. We can say we have challenges in Africa but in America too so let’s discuss them.”

Githongo believes that reforms such as declarations of assets by public officials, state-financed elections, an international judiciary to fight corruption, transparency in the world’s tax havens, and more accountability in anti-corruption provisions in the next round of international development goals are some useful anti-corruption instruments.

Corruption’s impact on security cannot be underestimated. Until Kenya’s architecture of corruption is demolished, the country may have to brace itself for more flamboyantly ruthless attacks like the 2013 Westgate Mall massacre.

Rudi-Ann Miller is a junior in Silliman College. She can be contacted at rudi-ann.miller@yale.edu.