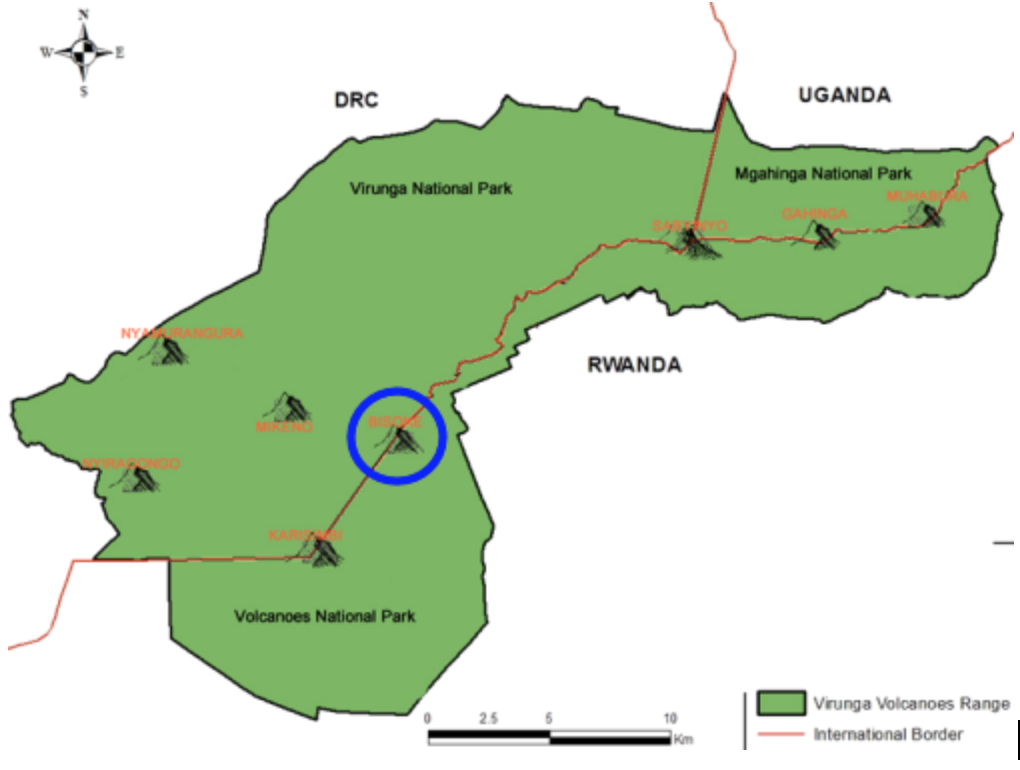

Featured image: Map of the Virunga Massif which spans Rwanda, the DRC, and Uganda.

By Claire Zalla

The journey up the volcano was less of a hike and more of a battle through mud averaging eight inches deep. The jungle on either side was thick and green, so it was impossible to tell how far we had reached up the slope. For all we knew, we could still have been tangled in the foothills or about to crest the peak to see the famous crater lake of Mt. Bisoke.

After about half an hour of hiking, we realized we had company. We could see flashes of them watching us through the trees: men dressed in camouflage and carrying AK-47s.

We had met our guides Elphas, Fidele, Mupenzi, and Mr. D, among others, at the base of the volcano. They were rangers dressed in knee high boots who make the challenging climb, that only about forty percent of tourist hikers complete, several days a week. But no one had introduced us to these men who hiked several yards ahead of us, nimbly climbing the demanding terrain with ease despite carrying heavy guns, while we struggled with nothing but water bottles. They would pause momentarily to wait for us, scanning the trees.

We learned that they were members of the Rwanda Defence Force tasked with protecting our hiking group from poachers—both Rwandan and those sneaking over the Rwandan border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Having the highest biodiversity of anywhere in the world, the Virunga Massif, a chain of eight volcanoes which spans parts of Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC, is considered the birthplace of conservation in Africa. It is maintained by three separate parks: Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda, Virunga National Park in the DRC, and Mgahinga Gorilla National Park in Uganda. Along with its beauty, however, Virunga is rich in natural resources like charcoal, and these natural resources are major sources of revenue for the armed militia in the eastern DRC. The illegal extraction of these resources can result in enormous financial returns (approximately $170 million in 2017 in the DRC). No natural resource, however, is more prized than the mountain gorilla. Only about 786 are left in the entire world, and 480 make their home in the Virunga Massif. The gorillas are valued for their meat, as hunting trophies, and for witchcraft or healing remedies.

Getty Images: a silverback gorilla killed by people involved in the illegal charcoal trade.

In the three parks, being a ranger is a family affair. Many rangers are the children or grandchildren of rangers. However, because this protected area contains so many temptations for poachers, being a ranger is a highly dangerous job. 170 have been killed over the past two decades by poachers or remnants of armed militias in the DRC (left over from the Second Congo War 1998-2003), causing the job to be called the most dangerous in all of conservation. In Volcanoes National Park in the DRC, which is considered exponentially more dangerous than the Rwandan park we hiked due to its past civil war and unrest in the country, a Congolese park ranger named Rachel Makissa Baraka, 25, was shot dead by militiamen while defending two British tourists.

Fortunately, ecotourism and hiking in Rwanda is much safer. On the U.S. Department of State travel advisory rating scale from one to four, with one being “exercise normal precautions” and four being “Do not travel,” The U.S. Department of State gives Rwanda a one, a lower score than Belgium. In 2017, there were 94,000 visits to Rwanda’s national parks. Trips to Volcanoes National Park accounted for 38% of all visits and raised $17.1 million, which was 90% of the total revenue raised from all park visits,. Rwanda is aiming to be one of the premier tourist destinations in all of Africa, and for this reason, they are very concerned with the safety of tourists in its parks—hence, our friends with the AK-47s, just in case.

When we reached the top, we posed for a group photo with our rangers who had helped us complete one of the most challenging hikes we had ever attempted. I looked around to try and include our guard in the photo, but he was hanging back. We never got a chance to thank him, but we were grateful he, and our rangers, were there.

Taken as we began our descent from the Crater Lake.

Claire Zalla is a junior in Pauli Murray College. You can contact her at claire.zalla@yale.edu.