by Sanjena Sathian

Cyprus is a strange place. It’s small: 60% the size of Connecticut – and yet it’s like the whole world is here in some ways. We’ve wandered our way through circles of diplomats, who seem wholly unconcerned about tensions exploding on the island; we’ve been inside the United Nations Protected Area and visited the peacekeeping forces (UNFICYP) and the UNDP and everywhere we go we seem to encounter expats and we’re always hearing at least five languages at once. This is a place burdened with fundamental problems of what nationhood means, and yet surrounding its very local problems is a web of transnational and international interest. Cyprus seems to be where worlds are converging.

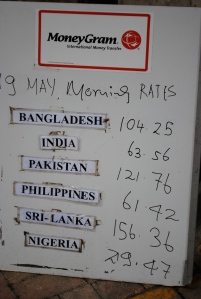

As if political divides between the northern (“Turkish”) Cypriots and the southern (“Greek”) Cypriots weren’t enough, Cyprus has a whole new set of issues of multiculturalism to deal with on top of trying to reconcile this ethnic conflict dividing the island since the 60s. Everywhere we go in southern Cyprus, we see ads proclaiming the cheapest prices for wiring money home – home being Sri Lanka, Nigeria, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Russia … it seems like there are more non-Cypriots here than Cypriots. I’ve used my limited Hindi and Nepali skills here already more than I’ve even attempted to communicate in Greek. And the north, too, has its fair share of separate immigration issues as it’s flooded by rural Turks coming to settle.

The “Cyprus problem” keeps being identified to us differently: some have called it a civil war, others an ethnic conflict, and others a totally non-ethnic and purely political situation. Whatever it is, the state of multiculturalism and immigration will affect the way the two sides interact with one another. In the south, the sentiment we’ve gotten is that the increasing numbers of immigrants are turning this into a more xenophobic place – and if you can’t tolerate immigrants in your society, how can you ever tolerate uniting with people who’ve been your enemies for thirty years?

I can’t help but feel that Cyprus exemplifies a lot of what our generation has grown up understanding intiutively: the complexities that globalization bring to problems of nationalism. This is a conflict that’s been founded on fictions of the nation, on the imaginaries of national identities – but these identities are not essential or inherent: they are in constant flux, and that mercurical nature comes from an integrating and globalizing world. As Cypriot nationhood begins to change, and as more and more elements of other nations and cultures penetrate the two sides, the fundamental building blocks of this conflict, a national identity, will have to change. I wonder if that’s the only thing that will force this island into action. Finally.