By Anna Russo

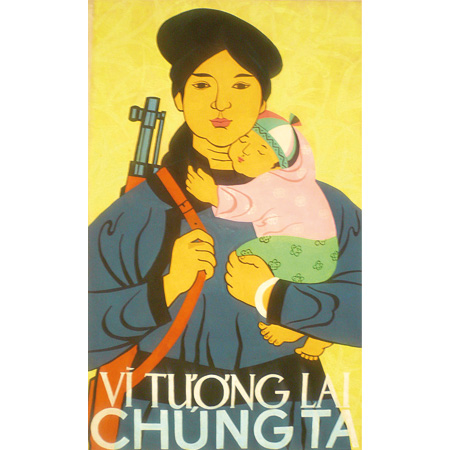

Nixon held a swastika, Ho Chi Minh held a baby, and every woman held a gun.

Perusing through propaganda posters jolted my attention toward Vietnamese politics for the first time. The hammers and sickles floating above strong workers, Ho Chi Minh and Lenin deified in a sea of red, and paintings of a mobilized military society all called to attention to a Vietnam that I thought had been left behind: a country characterized by strict adherence to doctrine, a country galvanizing nationalistic spirit, a country that truly relies on propaganda.

These posters were on display in a shop whose English “Propaganda Posters” sign attracted fascinated foreigners in a district in Hanoi where expats, tourists, and locals alike congregate for cheap food and cold beer. I entered the shop planning to revel in the ludicrous brainwashing of days gone by, to mock the irony of a communist Vietnam.

But the next day the hammer and sickle appeared again as wall art in a posh café frequented by local students, mirrored by another poster displaying crushed missiles bearing the labels America and France. 2014 marks the sixtieth anniversary of Vietnam’s independence, and to celebrate this anniversary, huge posters celebrating Ho Chi Minh populate the city, making the Socialist Party’s yellow star ubiquitous in the streets of Hanoi.

Over dinner, one of us brought up that our generation is the first to accept a state governed by the duality of socialism and capitalism. Vietnam is, of course, exactly one of these states; following the Doi Moi reforms of 1980s, the nation’s “socialist-oriented market economy” fueled Vietnam’s growth. But the contradiction inherent in a “socialist-oriented market economy,” an economy in which a hammer and sickle provide the backdrop for hundreds of storefront businesses, begs the question: how can these ideologies coexist?

In America the answer seems simple: capitalism always wins. Vietnam is no longer the nation ravaged by civil war and led by Ho Chi Minh’s doctrine, but instead the world’s new manufacturing hotspot. To us, the legacy of war fizzled as America became an invaluable trading partner and communist ideology was eclipsed by capital gains.

But in Vietnam, I realized that assumption clearly requires reevaluation. As Americans interested in Vietnam’s politics only to the extent that it influences their economy, we tend to only focus our attention on Vietnam’s market economy – whether it is socialist oriented or not is of little consequence to our trading needs. But are these propaganda posters really indicative of the “socialist oriented” nature of Vietnam?

These posters clearly permeate Hanoi and the rest of the rest of Vietnamese society, and without even considering the extent to which the posters themselves influence popular thought, in what way do these posters even rally support for socialism? Yes, there is the hammer and sickle, but what does that mean to the Vietnamese? These posters are praising the government and those in power, the Socialist Party – but what are they really saying about the importance of true socialist ideology?

This does not indicate that capitalism reigns supreme and that socialism is dead, but rather points out the inescapable contradiction that the “Propaganda Posters” store so perfectly exemplifies. The shop is capitalizing on a Western trend of cynicism, catering to an ironic love of communist posters and depictions of tentacled, green Nixon monsters – at once both profitably belittling its ideology to mocking Westerners and accepting these socialist ideals as central to the Vietnamese experience. I am no political philosopher, but I must ask – is this sustainable?