Every major city is plagued with graffiti. Immediately upon arriving in Sarajevo, I saw that it was no exception. Through the windows of our over-crowded van, I caught sight of colorful arrays of taglines, familiar cartoons, caricatures and bubble letters covering just about anything with a flat surface. From vandalized run-down apartment complexes that were still coated with bullet holes to beautifully historic religious sites, I was able to deduce that graffiti played a large part in the culture, an unfortunate but colorful byproduct of corruption, poverty and weak infrastructure.

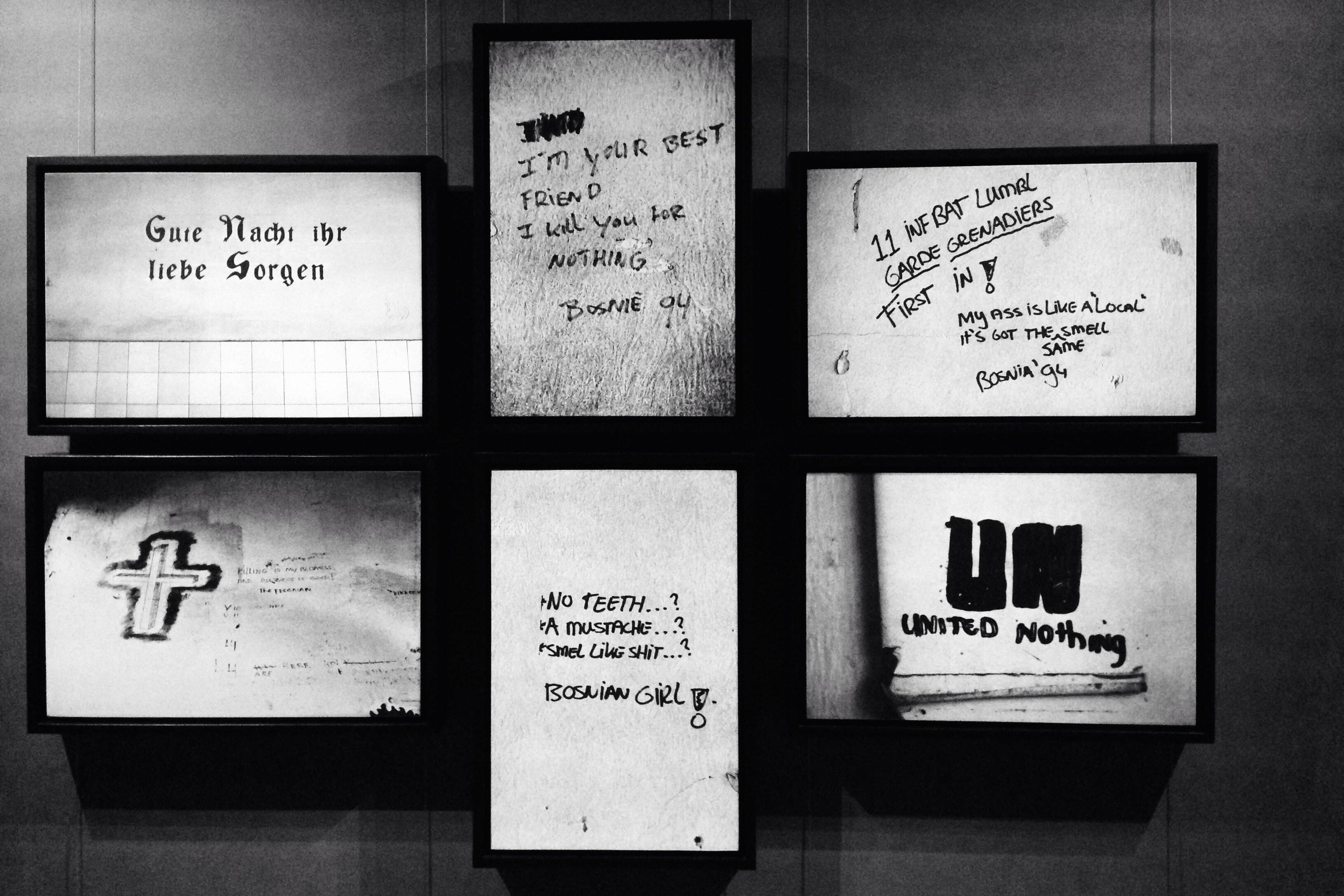

However, graffiti was not always just a form of vandalism, nor is it entirely that today. Graffiti was used during the war as means to convey political beliefs and communicate ethnic division. Citizens used graffiti to express their discontent with the United Nations, distrust for their own friends and neighbors, hatred for other ethnic groups, and resentment of political leaders. Ethnic groups and political parties used graffiti to mark their territory, alluding to their hypernationalist identity.

Today, although the war has ended, the conflict is far from resolved. Staggering corruption levels have worsened the country’s struggling economy and perpetuated ethnic tensions. While political statements remain a large part of the graffiti culture, the younger generation has taken some artistic inspiration from the West: meaningless tags and phrases are also scattered across the walls of a country so rich with history and culture.

Clara Mokri ’18 is in Timothy Dwight College. Contact her at clara.mokri@yale.edu.