Finding Missing Relatives: Activist Sylvia Aguilera Garcia’s fight against kidnaps in Mexico

Activist Sylvia Aguilera Garcia’s fight against kidnaps in Mexico

By Marina Yoshimura

In Mexico, families of missing relatives must publicly speak out against their loved ones’ disappearances to get the government’s attention. Although the Mexican government is responsible for finding and protecting its citizens, its efforts are inadequate. Activists often assume this mantle instead of the government. The challenge is whether these activists can be safe while they fight for the safety of the families of missing relatives. Activists are especially at risk because they become targets of gangs and other organized criminal syndicates. Passion is not enough to solve human rights issues; strategic courage is integral.

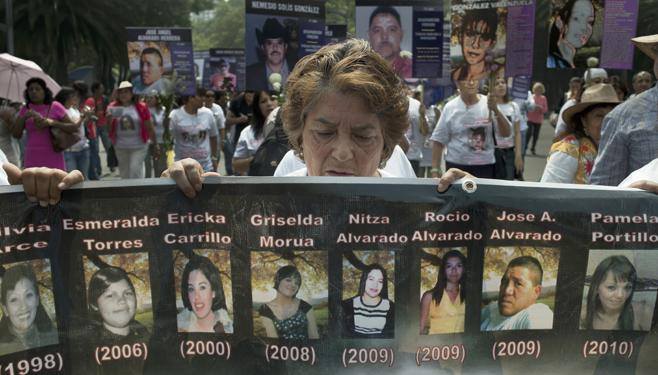

With patience, perseverance, and passion, human rights activist Sylvia Aguilera Garcia has saved lives and bridged families of missing relatives in Mexico with the Mexican government. A 2018 Yale World Greenberg Fellow, Garcia served as Executive Director of civil association Centro de Colaboración Cívica, which brings together civic organizations and governments to help families in Mexico find their missing relatives, an “epidemic” of sorts. In 2018, 15,000 young people disappeared in Mexico. She has not only pioneered a movement, but has also kept stakeholders on board by listening to and inspiring civic engagement among families of missing families, and making sure they take the issues to the Mexican government.

It’s only recently that families and the government have been able to hold official joint dialogues. This is in part because families of missing relatives had lacked a support group; they had tried to search for their missing relatives on their own. But the alarming crime rate has pushed the issue to the political agenda and has become a key issue for both Mexican citizens and their government. Dialogue between citizens the government has facilitated searches for families and encouraged civic engagement. Citizens are no longer on the sidelines of the country’s circumstances; they are at the forefront, and they are the trailblazers.

Governments and civic organizations rarely play on an equal playing field. Platforms for joint dialogues are necessary but often non-existent or inadequate. Such systems are especially difficult to implement and enforce through governments that struggle to connect with their people. The Mexican government is one such case. Garcia, who has spent more than two decades working on peace-building, has a solution to the government’s lack of transparency: to empower citizens to use their voice. She provides a platform for the government, citizens and civic organizations to foster relationships with one another to facilitate conversations that pertain to all of them. For example, Garcia arranges meetings with families of missing relatives– treating the families as the experts– to “start building small groups to help each other and try to understand to look for their relatives.” Much of the success in these talks lies in Garcia’s strategy. She doesn’t just speak up about the kidnaps or the human rights violations; she also chooses the right people to advocate for them. “Consult the families. Treat the families like they are the experts,” she said. “Human rights entails more than just a legal framework,” she added. She used her expertise– her undergraduate degree in Social Psychology and a Masters degree in Peace Studies specializing in Working with Conflict– to focus on the facilitation of disk processes to change and bring different voices to change the law.

Human rights requires governance. Given her expertise and violence in Mexico, she decided to implement strategies to address human rights violations in her country. As Executive Director of the CCC, she established coalitions and solicited stakeholders, such as by working with a projects director from the United Nations. Organizations such as the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights and Amnesty International helped her build a participative process. Garcia created an open space for Congress to discuss specific topics, such as dealing with security issues in Mexico. Not only does she understand stakeholders’ positions, such as the families and victims of missing relatives and the Mexican government, but she also understands how to manage them. Her leadership allows her to create a framework for these groups, and empowers them to find the relatives who are missing. By doing so, the Mexican government can effectively address these families’ needs– to find their relatives and prevent future disappearances– and in turn earn citizens’ trust. They reach a win-win solution.

Meetings are not enough to keep agreements sustainable. This is when the law comes in. An amendment in Mexico’s human rights constitution was necessary, Garcia said, because some groups exercised more coercive strategies against citizens, while others avoided confrontation. The law would include a reform in the judicial system and to have a law about human rights victims. Garcia developed ways for them to reach a common agenda. In 2011, she worked with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the projects director in charge of human rights. After amending and implementing the law, the next step was to solve the conflict. Some had been searching for their relatives for years. Some became advocates and established support groups with other families whose relatives had also disappeared. They became more connected to the government. These families began to build coalitions because, as Garcia put it, “they understand that it’s not that easy to swim in the sea of bureaucracy and prosecutors.” They began to help one another and look for their relatives, the majority of whom were women. They became the breadwinner in patriarchal communities. Gender roles began to shift. Despite their efforts, disappearances and violence persist in Mexico.

Strategic courage is key to upholding human rights. Although principles may be consistent, the world is not. Crimes are prevalent. Injustices plague society. Fear brings us down. But these problems don’t have to define our world. Garcia keeps the government in check and solves conflicts by empowering civic organizations, saving a community, and protecting human rights. Working on the right cause at the right time with the right people can make a world of a difference.

Marina Yoshimura was a visiting student from Japan at Yale. You can contact her at: myoshimura@akane.waseda.jp.