By Simona Hausleitner

Today, traveling from the bustling port city of Shanghai to the crumbling ruins of the Acropolis in Athens takes less than a day by plane. A thousand years ago, however, the journey from China to Europe was not quite so simple: Western traders hoping to bring back luxury items like porcelain, spices, and precious metals—as well as diplomats inspired by tales of the Great Khan’s Imperial Palace—had to take a perilous route through the steppes and grassland terrains of Eurasia to get to the shining beacon of unfamiliarity that was China. This route became known as the “Silk Road,” a term coined in 1877 by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen to describe the network of trade routes connecting the Far East with the Middle East and Europe. These routes facilitated the exchange of a huge volume of goods between East and West; caravans filled with everything from string beans and pomegranates to leopards and cinnamon journeyed across the mountainous regions of Asia. At the 2017 opening ceremony of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave a keynote speech describing how “the ancient silk routes spanned the valleys of the Nile, the Tigris and Euphrates, the Indus and Ganges, and the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers. They connected the birthplaces of the Egyptian, Babylonian, Indian, and Chinese civilizations as well as the lands of Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam and [the] homes of people of different nationalities and races. These routes enabled people of various civilizations, religions, and races to interact with and embrace each other with open minds. In the course of exchange, they fostered a spirit of mutual respect and were engaged in a common endeavor to pursue prosperity.” The importance of the Silk Road has persisted through time as a monument to the intercultural exchange of knowledge and ideas. In a similar spirit of openness and mutual benefit, China unveiled a new undertaking of massive proportions, aptly nicknamed “The New Silk Road,” in 2013. Whereas previous foreign investment efforts have typically been highly decentralized, this initiative consolidated China’s diversified projects in Eurasia, Latin America, and Africa under a single umbrella, thus marking a fundamental shift in the way world powers conduct economic activity.

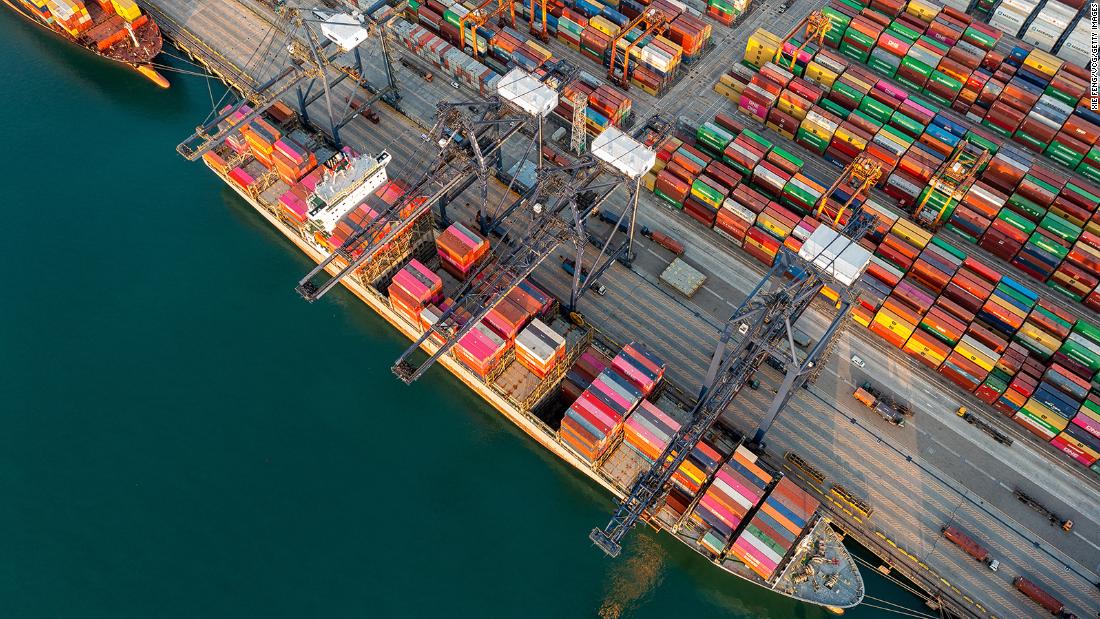

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s plan for economic integration across the East and West, facilitated by a land “belt” running from China throughout much of South and Central Asia into Europe, and a maritime “road” linking coastal Chinese cities with ports in Africa and the Mediterranean. According to recent data, 140 countries have signed on, accounting for a third of world trade and more than 60 percent of the global population. Over the past few years, the BRI has even scaled up to include Latin America and the Caribbean within its purview. Key components of the project include building a 12,000 kilometer railway from London to China, creating a highway system throughout much of Southern Asia, and instituting a pipeline that would end up transporting about fifty-five billion cubic meters of gas annually from the Middle East to China. A far cry from the communist policies of Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic, the BRI has been praised as a step towards enhancing international collaboration through the establishment of an open economy. While proponents of the BRI discuss its potential to increase global trade, lift millions of people out of poverty, and enhance scientific and technological advancement through cooperation across countries, critics view the BRI as a way for China to accumulate geopolitical influence through economic expansion. In addition, scholars in the United States and abroad have drawn attention to the BRI’s lack of transparency, damaging environmental impacts, and predatory lending, raising concerns about unsustainable debt and high development costs. In response to these criticisms, Chinese President Xi Jinping has reaffirmed the country’s commitment to implement green practices and to work with partner nations in developing more sustainable plans for building infrastructure. Recent years have seen significant structural readjustment of the BRI, ranging from anti-corruption campaigns to partnerships with major multinational financial institutions. Yet, the question remains: do the relative benefits of the Belt and Road Initiative outweigh its potential harms? And is this policy primarily a form of neo-imperialism meant to expand China’s geopolitical hegemony, or is it a project that will spur development in poorer countries by bringing them into the global economy?

Ultimately, this is a difficult question to answer, mainly because it necessitates the consideration of how the Belt and Road Initiative is conceptualized and implemented in each country, as well as which interests are driving this implementation. This article seeks to clarify and analyze some of the more contentious issues surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative, while also evaluating how a project of this magnitude will change the global socio-political landscape for years to come.

The BRI in Practice

China’s rise to the forefront of a free-market, globalized economy over the past decades has been accompanied by a record amount of financing, both for public and private sector projects, in countries around the world. As part of the BRI, China provides loans to host countries for the purpose of building infrastructure like roads, railways, ports, and electric grids. Studies show that 42 countries have debt exposure to China exceeding 10 percent of their GDP, and many more are defaulting on their loans or suffering from economic fragility.

The World Bank maintains extensive databases on global debt and publishes an annual report on debt in developing countries. David Malpass, president of the World Bank Group, remarks: “One notable thing is how hugely the amount of debt has shifted towards China being the creditor. . .in 2000 there was a major shift to the point where China alone makes up some 60% of the total official credit of the world today.” This has major implications for future relations between China and the rest of the globe, as modern power dynamics are based heavily on the flow of money from one country to another.

Dr. Cecilia Han Stringer, a senior researcher with the Global China Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, gives insight into the financial mechanism by which the lending process occurs: “It’s helpful to think about China’s overseas finance in terms of public and private finance. Public finance means loans coming from the Chinese Development Banks, which are the China Development Bank and the China Export Import Bank. They operate domestically, but they also provide major loans for overseas development.” She elaborates that the advantage of this type of development finance is that Chinese banks are often able to deliver funds much more rapidly than local banks in host countries, meaning that infrastructure projects can occur more efficiently. Dr. Stringer remarks that the second major type of financing is private, meaning that either “commercial banks, like the Bank of China, lend money for overseas development,” or Chinese companies invest their assets and “may go directly overseas and provide equity, or foreign direct investment” to the host countries. While public financing is subject to bureaucratic regulation by Chinese agencies, such as the Ministry of Commerce and the NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission), which have oversight processes and regulations for loan amounts, Dr. Stringer maintains that private finance is more of a ‘black box.’ The lack of transparency in these lending processes is a major concern raised by other countries and multinational institutions. Mr. Malpass elaborates on how China has kept some of its dealings under wraps: “since 2014, China has started putting non-disclosure clauses into all of its loan contracts. . .And so that makes it very hard for [the public] to know what the interest rate is, how many years they have to repay the loan, or what the terms and conditions of the contract are.”

Specifically, with regard to the BRI, some national leaders have accused China of engaging in a strategy known as “debt-trap diplomacy,” which involves deliberate over-lending, thereby luring countries into unsustainable loan agreements. After the borrowing country begins to experience financial hardship resulting from unpaid debt, China can seize assets, thus expanding its economic and political power in other regions.

Despite these criticisms, however, there has not been sufficient evidence to indicate predatory lending on China’s part. In Malaysia and Sri Lanka, the most frequently cited ‘victims’ of debt trap diplomacy, BRI projects were initiated mainly by the host governments, and growing financial instability resulted from local corruption and the misallocation of funds rather than high-interest loans. Dr. Stringer agrees, explaining that “a lot of research is really indicating that this debt-trap diplomacy, as it’s called, is not actually an intentional strategy on China’s part in order to gain more economic control over countries that it cooperates with. The primary reasons that China has set for itself in promoting the Belt and Road Initiative are more around cooperation, development and expanding markets.”

Clearly, this issue is complex and multifaceted, with many opposing viewpoints—some argue that China is focused on building geopolitical power by trapping poor countries in a cycle of debt repayment, while others promote the idea that China is looking to facilitate commerce and trading opportunities while still getting a return on investment. One area that China could improve upon is transparency; by consolidating and clarifying its interest rates and lending practices, China could reduce some of the backlash it has faced from the international community.

Impact on Local Communities

In evaluating the impacts of the BRI, it is important to analyze how its policies directly affect the local communities in host countries. Despite complaints of structural inefficiencies, wasteful spending, and low profitability, the BRI has had tangible impacts in the fields of science, technology, health, and economic growth. In recent years, China has implemented the Program for China-Africa Cooperation on Poverty Reduction and Public Welfare, signed an agreement with the WHO on health cooperation, trained thousands of professionals in public health management and disease prevention, and launched the China-South Asia science and technology partnership programs. Beyond these programs, “the main economic benefits of the Belt and Road Initiative are transferred through local infrastructure development,” says Dr. Stringer. “The average person in a host country can have better roads, better railways, and a more stable electricity supply.” Some might argue that these actions are self-serving, and that China is simply doing them to expand its economic and political control over regions throughout Africa and Latin America. Projects like infrastructure development, the construction of power grids, and the establishment of new trade routes between previously disconnected regions bring to mind the Age of Imperialism, specifically how European countries would assume power in ‘Third World’ nations under the guise of improving the economy, all the while exploiting these poorer nations for their own benefit. However, there is a key difference between neocolonialism and the Belt and Road Initiative: recipient countries play a crucial role in shaping the projects of the BRI, since China cannot force sovereign nations to accept their involvement. Thus, the BRI is built through a series of compromises and bilateral agreements, rather than from unilateral decision-making by the Chinese government. In contrast, neocolonialism is based on a more unequal power dynamic, where the host country often has no means of resisting geopolitical takeover by another nation. Jingjing Zhang, director of the Transnational Environmental Accountability Project, explains that “The impact of investment aid depends on two factors: the host country’s government and the management and legal requirements for financing. First, it is necessary that the regime can guarantee that benefits are actually transferred to host countries. Second, countries must require business entities to conduct their due diligence and evaluate social impacts of new projects.” Though China plays the dominant hand in terms of financing capabilities, the long-term impact of investment projects may be more closely related to the political and economic conditions of the host country.

There has been resistance. Dr. Stringer highlights the “mixed reactions” of host countries: “I think oftentimes, national governments are really enthusiastic about cooperation with China and being able to access additional sources of capital. But local communities may see it as encroaching and changing their local area, and they may not welcome that. I think there’s a lot of hostility towards China in particular, because it does feel like neo-imperialism to a lot of communities where they’re seeing Chinese companies and Chinese workers come in and really transform the landscape. For example, there are mega projects in the power plant development sector, such as the Myitsone Dam in Myanmar, or the Lamu Coal Plant in Kenya, where local communities have really mobilized resistance and successfully delayed these projects.” She also discusses how the relative speed with which Chinese firms have engaged in land transformation may lead to some communities, especially in areas where raw materials are sourced or where development is occurring, to have difficulty adapting to these large-scale changes. Ms. Zhang further elaborates on China’s frequent “lack of understanding of host countries’ culture and laws,” explaining how “Chinese companies take advantage of weak regulatory systems and violate indigenous communities’ land rights. In extreme cases, Chinese companies have used armed force to protect their property, which shows disregard for the locals’ constitutional rights, specifically in countries like Ecuador and Peru.”

Overall, the relative harms and benefits of China’s involvement must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis: whereas some regions could immensely profit from the establishment of better maritime trade routes and a more stable power supply, structural inefficiency and local corruption might make bilateral cooperation unsustainable in other areas.

BRI and the Environment

As the climate justice movement progressively becomes more important in the public and political sphere, it has become increasingly necessary to assess the environmental impacts of development projects like the BRI. Although the BRI has tremendous potential to transform the economic landscape of countries across the world, it carries the very real threat of leaving environmental damage in its wake.

Some of the BRI’s main corridors pass through areas deemed ‘ecologically sensitive,’ and the construction of thousands of miles of roads and railways could critically endanger the plant and animal ecosystems native to the region. Along with wildlife and habitat disruption, the BRI has been linked to unsustainable land use, harmful mineral extraction, the destruction of biodiversity, water quality problems, and industrial pollution. Another major concern is that China is using the BRI as a funnel to export its fossil fuel-based economy to developing nations. Political pressure at home could lead some Chinese policymakers to support the sale of unsustainable coal technology abroad, contributing to the production of more greenhouse gas emissions for generations to come.

Recent years have shown a strong effort on China’s part to increase the sustainability of its ventures while reducing its investment in power sources like coal, oil, and natural gas. Dr. Stringer discusses how international pressure and the desire to support environmentally friendly projects has pushed China to implement new policies regarding the environment: “Some of our recent research from the GDP Center has highlighted the potential for ‘debt for nature’ or ‘debt for climate’ swaps with China, where countries that have high indebtedness to China can apply for debt relief in exchange for mitigating environmental destruction, protecting local habitats, or preserving biodiversity.”

She also explains the importance of a comparative approach when analyzing Chinese development, since development as a whole usually cannot proceed without some environmental damage occurring due to landscape transformation. Dr. Stringer remarks: “My past research looked at the CO2 emissions intensity of power plants that are using Chinese contractors versus those that are using local contractors or contractors from other countries. And what I found was that the power plants with Chinese involvement actually had lower emissions intensity, indicating that they had higher quality technology relative to those other countries. So for some sectors, especially electric power development, or high speed rail, China has developed the technological edge from building up their own domestic industry in these sectors, and is able to take that technology overseas.”

Clearly, the environmental issue is a divisive one, and China’s lack of transparency toward the international community has compounded the difficulty of evaluating the BRI’s impact on the landscapes of developing countries. The concept of a “green Belt and Road Initiative” has emerged over the past few years, with China reaffirming its commitment to limiting environmental harms by meeting the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement and significantly reducing investment in coal and oil. With the increased focus on environmentalism, however, it is unlikely that China will be able to continue on its current track as the world’s leading producer of coal if it wants to continue making deals with developing countries, many of whom are aspiring leaders in the world of green, low-emissions technology. Ms. Zhang agrees with this perspective, noting that even if China makes progress towards reducing coal mining, “manufacturing, bauxite mining, oil refineries, and mineral extractions still contribute to substantial environmental damage.”

Future Implications

When we look back on the question of the Belt and Road Initiative’s relative benefits and harms, it is clear that there is no simple answer; rather, a complex interplay of economic, environmental, and political considerations must be taken into account. Fearful Western leaders will likely always see China’s actions as an intentional power grab meant to increase its geopolitical influence. While there is an element of financial dependency whenever China extends a line of credit to developing countries, it remains unclear whether this is simply an aspect of the lender-borrower dynamic or an intentional move on China’s part. As to whether the Belt and Road Initiative is an extension of neo-imperialism or an altruistic humanitarian investment, it is clear that the motivations behind China’s actions must be weighed against outcomes, especially in terms of poverty reduction, economic development, environmental damage, and expanded trade capacity in countries around the world.

Xi Jinping’s manifesto that “China will never close its open door to the outside world, and the country welcomes all other nations to ride on the ‘tailwind’ of its development” is telling for the future. Regardless of whether China’s underlying motive is geopolitical dominance or international cooperation, the Belt and Road Initiative will remain a hotly debated topic for years to come.

Simona Hausleitner is a first year in Branford College. You can contact her at simona.hausleitner@yale.edu