Sacred Loss: The Spiritual Consequences of Climate Change

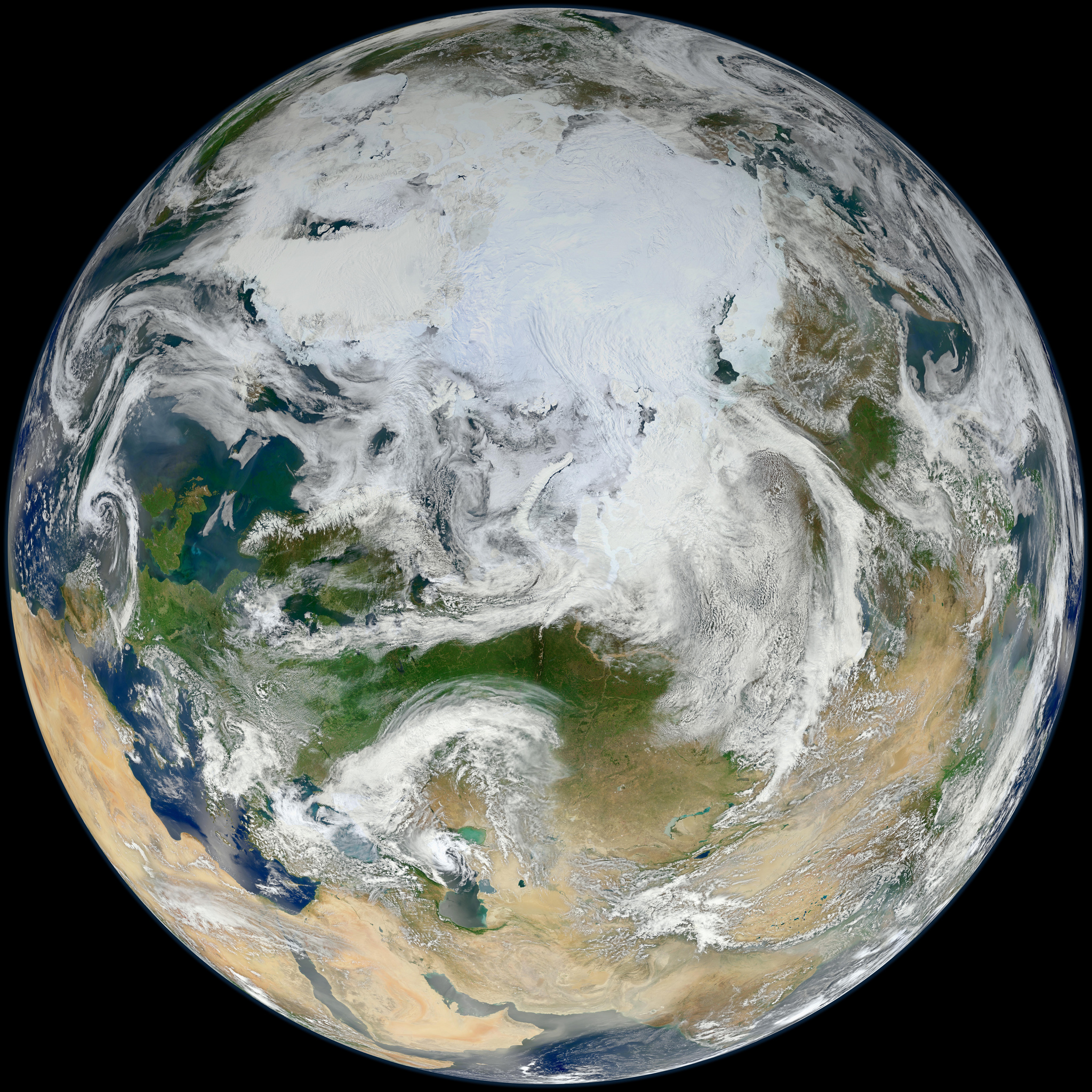

Featured image: “Humans belong in nature. We rely on the Earth to supply us with everything we need.”

[hr]

By Abigail Grimes

[hr]

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ount Khawa Karpo, located in Eastern Tibet, is a world of its own. It reminds one of what stone really is—not triangles pressed against the sky or rounded cliffs, but a body, oceanic blue or volcanic grey, not as much of a place as it is an entity of its own.

It is an entity, too, for the people of Deqin County. Khawa Karpo and the glaciers and waterfalls around it embody deities and spirits. Animals and plants on the mountain reflect the spiritual life in the landscape. Grapevines twist and blossom in the lower valleys while stalks of barley wisp about in the wind, hundreds of feet above. Villagers harvest timber from forests high in the mountains. In the summer, herders lead yak up to graze in alpine meadows, until the autumn comes, and they are led down into the valley again. Sometimes, the sun hits the peak and turns the snowcaps the color of a thick tuft of buckwheat. In the religion of the Tibetan people living in the villages around Khawa Karpo, hunting or gathering plants on sacred mountain sites can anger the deities of the mountains.

[divider]

“Khawa Karpo and the glaciers and waterfalls around it embody deities and spirits.”

“Khawa Karpo and the glaciers and waterfalls around it embody deities and spirits.”

[divider]

Khawa Karpo is home to many small villages whose villagers see sacred manifestations in waterfalls, glaciers, and mountain peaks. It is the physical embodiment of a warrior god. And it is on the Tibetan plateau, part of the nation emitting the highest levels of greenhouse gasses. It is victim to one of the highest rates of climatic change in the world.

[hr]

Humans belong in nature. We rely on the Earth to supply us with everything we need. Naturally, religions almost universally address human relationships with nature. When asked if there are any cultural motivators that could make certain religions more concerned with climate change, Professor Justin Farrell answered, “It is important to recognize that there are vast differences even within the same traditions. With that said, most major religions have within their theology, sacred texts, and practices a sense that nature is somehow special or sacred, and there are moral boundaries around how the earth’s resources should be used and shared.” Professor Farrell, an associate professor of sociology in the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies (F&ES), is the author of The Battle for Yellowstone. He studies the relationships between the environment and culture, as well as rural inequality and social movements.

“These [religious guidelines] can differ wildly, and in some cases, religion has promoted human dominion over nature—thereby encouraging its exploitation. So, it can cut both ways,” Professor Farrell said.

American evangelicalism, for example, has at times cut deeply into the Earth. Ideas of human dominion over nature have snowballed into the systems we now accept as everyday—factory farming, logging, and overfishing. Westward expansion, which displaced Native peoples from their own sacred lands and encouraged massive human manipulation of the environment, was centered on concepts of manifest destiny and divine provision.

Professor Farrell further described climate change as an “ethereal and long-term issue,” and noted that some religions with legacies of human dominion are moving now toward greener ideologies. For example, Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’ addresses climate change as a moral issue: “This sister (earth) now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her.” And religion, Professor Farrell says, “can lend a unique moral voice to issues of climate change,” in addition to providing structures able to disseminate information and encourage environmental action.

Professor Robert Mendelsohn, also of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, agrees that religion can lend a moral voice to environmental issues—but he argues this isn’t enough. His work centers on the economic valuation of the environment and natural resources. Using Buddhism as an example, Professor Mendelsohn cited the concept of interconnectedness— “You have to look at how your actions affect all things, not just yourself. And all things could mean the people around you, but if you think bigger than that, it also means the life around you—that your actions change all of that life, and you need to take that into account.” Religion, he believes, can present an ideal, but religion’s role as a comforting and healing force in the lives of many means that other incentives are needed to help people live up to their ideals— namely, economic incentives.

[divider]

“You have to look at how your actions affect all things, not just yourself.” (Quote from Professor Robert Mendelsohn)

[divider]

In a perfect world practitioners of religions that promote environmental stewardship, like certain sects of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Christianity, among many others, would avoid contributing to climate change. We know from experience that this is not the case—and few religious groups represented in the industrialized world have completely avoided contributing to climate change.

So economic measures, Mendelsohn argues, are a way to help people think more immediately about their choices regarding climate change—and thus help them to meet their personal or religious ideals. Mendelsohn says, in relation to Buddhism and encouraging others to think about the impact of their actions on others, “That’s actually exactly what economists are trying to do with policy prescriptions and climate change. They’re trying to get people, when they think about taking actions like using fossil fuels, to think about the consequences of using those fossil fuels on the planet at large, far into the future. The way economists have done that is saying, ‘Look, these fossil fuels should be treated as if they’re more expensive than they already are.’”

[hr]

A Google search for “climate change” yields 684,000,000 results. A Google Scholar search yields 3,340,000. For an American with reliable access to the Internet, it is easy to inform oneself about climate change. And it would seem, based on recent environmental trends—like using metal straws, carrying canvas shopping bags, or going vegan—that reducing one’s impact on climate change is relatively feasible for those who can afford to do so.

American consumers inarguably play a role in climate change—but how much of a role? The Guardian reported last year on the 2017 Carbon Majors Report, which found that 100 companies are responsible for 71% of greenhouse gas emissions. Among them are such notables as ExxonMobil, BP PLC, Shell, and Chevron Corp—all of these companies are investor-owned. And in the 20 years between 1988 and 2018, 25 companies were responsible for over half of industrial emissions.

Exxon stock, per share, is $82.49. According to an article by the Chicago Tribune, 54% of US adults have invested, and many of those who are are through 401ks, pension funds, IRAs, and mutual funds. Few own individual stocks—like those owned by investors in Exxon, BP, Shell, and Chevron. In general, a smaller percentage of the wealthy participate in investments—not the middle class.

It would seem that Whole Foods shoppers, reusable bag toters, and hybrid car drivers are not entirely responsible for 71% of carbon emissions. And that, really, Walmart shopping, plastic-consuming minivan drivers aren’t either—unless they happen to be invested in Exxon.

[hr]

Professor John Grim and Professor Mary Evelyn Tucker have been married for over forty years, and together, they coordinate Yale’s Forum on Religion and Ecology. They also contribute to “Journey of the Universe,” a multimedia project that fosters a closer relationship between humans and the universe in which we live.

To Professors Tucker and Grim, economic measures against climate change aren’t enough. “Science, policy, economics, law, technology—all [are] necessary, but not sufficient to get us to where we need to go, on climate change and on environmental issues broadly speaking. So we also need a moral force, we need ethics, we need the sense of climate justice [and] who’s suffering most—the poor.”

What is sufficient to get us where we need to go may be something bigger. According to Professor Tucker, “Religion in a broad sense implies orienting to the cosmos, grounding in Earth and Earth systems, nurturing with food, water, wine, and transforming with an ethical energy.” Tucker and Grim alluded to a specific loss of natural connection suffered by some Western religions, citing the Christian and Jewish holidays that occur at seasonally significant times. Professor Tucker mentioned the symbol of bread in the Christian tradition—bread, the body of Christ, and wine, the blood. This connection is now thought of more as tradition that as a connection to Earth. Modern Christians, the religious majority in the United States, are losing the connection to nature that earlier Christians saw easily. And modern churches, driven to in comfortable cars and carried out with microphones and projectors, make it even easier to forget that Christianity began in a society closely integrated with nature.

The performative aspects of modern environmentalism—the canvas shopping bags, the metal straws, the pins—they get at behavior. They show that a person cares, but they don’t always show why. Professor Grim spoke of a need for a deeper cultural shift: “It’s interesting to see several organizations talking about transitions— transition cities— or [about] transformation in particular realms of social activity, all the way down then to transformation of conscious… A few years ago this school (F&ES) did a conference in Aspen raising the question for ways forward and they named the volume that came out… “Transformations of Consciousness,” so there was a sense even within our school (F&ES) that addressing piecemeal issues would only go so far—that there was a need for some deeper considerations.”

The issue is that to change, we have to an internal moral impetus that makes it so abundantly clear that we are sacrificing for what is holy to us. In America, we may have lost what is holy—in our religion, and in our lives. There is, however, for everyone—across faiths, outside of faith—something we know is holy. It could be the sunshine coming off the Earth, the rivers in the woods near where we grew up, the tree outside our bedroom windows. We have to find these things again and remember to love them. And then we have to work for them—to root out who is to suffering, and who is to blame, and to make it right.

[hr]

The people in the villages at the feet of Khawa Karpo, who take their yak up to graze in alpine meadows and harvest walnuts, have watched the landscape change. Harvests are smaller, resources are harder to find, and food spoils more quickly in the warmer weather.

According to a study by an Oxford researcher and a researcher from the Missouri Botanical Gardens, when asked about the origins of these changes, some said litter left behind by tourists absorbs sunlight and releases heat and causes glaciers to melt. Local understanding holds that cutting down trees causes less rain, and increased electricity use causes increasing temperatures. For the most part, villagers blamed outsiders—tourists, nearby companies building roads and hydroelectric plants—for this activity.

But the villagers placed spiritual blame on themselves. The religious shortcomings of Tibetans—not praying or making offering enough, gathering medicinal plants in sacred areas, failing to stop tourists from dishonoring sacred sites—were also to blame in the eyes of the villagers.

And is it fair? For people who have never forgotten what is holy, who have protected what is sacred, and who have seen each day, for generations, a life worthy of awe in the mountains, to feel the change the most? For a villager under the shadow of Khawa Karpo to know the sacred glaciers are melting slowly, to feel that Khawa Karpo, the warrior, is angry, and to think that it may, just possibly, be her fault?

Abigail Grimes is a first-year in Pauli Murray College. You can contact her at abigail.grimes@yale.edu.