Unequal Inheritance: the Gender Inequality Mandated in Moroccan Family Law

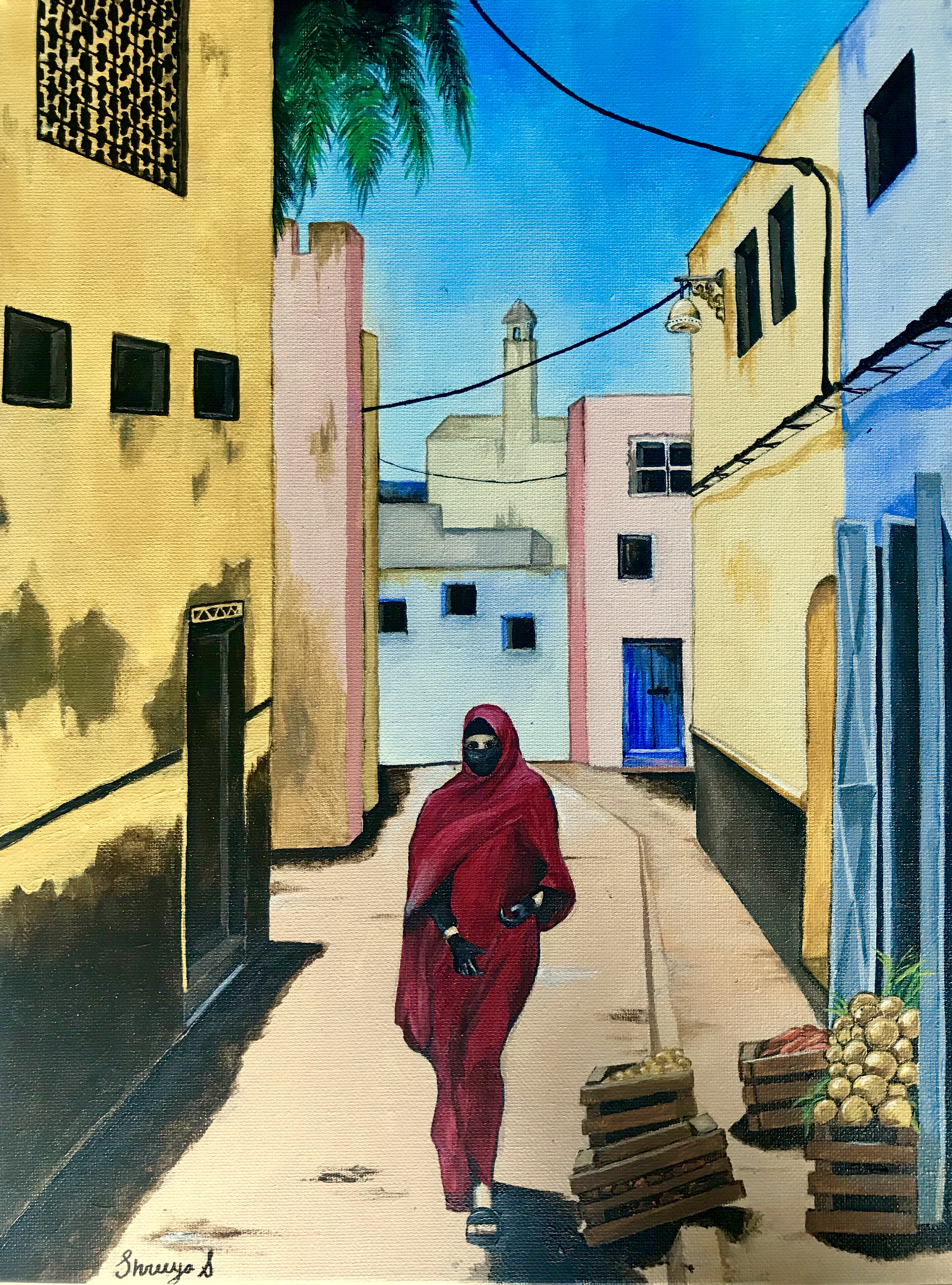

Featured image: This painting by the author is inspired by the many resilient and passionate women she met in Morocco.

[hr]

By Shreeya Singh

[divider]

[dropcap]“F[/dropcap]eminism can never be compatible with authoritarianism”

The Talila headquarters is reminiscent of a youth camp or hideout, with colorful posters and print-outs layering the wall, and bare mattresses lined up in a side room. Its discreet location, tucked away under a commercial building, however, shakes the mirage of peace. Across from me sits Nabil, the ideal image of a resistance leader, complete with wayward curly hair and tight ripped jeans that hug his skinny frame.

Nabil is the founder of a radical leftist advocacy group in Morocco. His organization, Talila, has engaged in anti-authoritarian guerilla activity, and believes in providing social services and education as an alternative to government-run options.

I ask him about whether the amended Moroccan constitution of 2011 gives him hope, and he leans forward on his folding chairs as he explains. “The 2011 changes to the constitution were not actually any more progressive than the past. It was all de jure change, not de facto. The fact that feminist movements of the time supported the new constitution was a betrayal and legitimized the King’s government.” Nabil’s gaze is unwavering, “feminism can and will never be compatible with authoritarianism.”

Nabil’s argument is that the 2011 constitution used something he repeatedly refers to as “blurs.” These “blurs” can come in the form of added words or a change in rhetoric of the law, but ultimately, they bring no real change in application to society.

He tells us that as an atheist himself, he still believes in the need to engage with Islam. “Islamic law in Morocco comes before international law. If we want to change the system, it is strategic to use its linguistic and institutional structure for the struggle.”

***

As 2017 drew to a close, the smoky paths of the medinas and traffic jams of Morocco witnessed women taking to the streets with chants of resistance. The women leading this feminist protest united against the Ta’sib, the inheritance law written into Moroccan family code.

The Morocco I saw this past May was vastly more calm than the one gripped by protest. It was one of tranquil shores, extravagant meals shared over handmade tea, and strangers who always went out of their way to help. It was a Morocco that seemed harmonious from the outside, with the nagging awareness of the absence of women in public spaces like beaches and cafes, hinting at a larger social divide.

Moroccan family code, or Moudawana, derives from traditional Islamic law, like much of Morocco’s legal code. Dr. Yasmine Berriane, a German-Moroccan scholar and professor at the University of Zurich, explains that “family law is based on an interpretation of religious texts and it is applied to all issues that relate to family or personal status code-marriage, inheritance, child custody, [and] divorce.” The law was codified after Moroccan independence from French colonization and has been reformed several times since, most recently in 2004.

However, despite progressive changes, the Moudawana’s Ta’sib still legally mandates that women in Morocco inherit less property than their male family members. Enshrined in Moroccan tradition for hundreds of years, the Ta’sib is a complex amalgamation of specific clauses, with common sense decrees on the passage of property from parents to their children, and more controversial ones such as “female orphans who do not have a brother must share the inheritance with the male relative closest to the deceased … even if unknown [has] never been part of the family.”

But the tides have been shifting. 2017 saw common people protesting the law in the streets, and in March of 2018, one hundred influential Moroccans–including actors, politicians and prominent academics–signed an official petition against the Ta’sib.

One of the spearheads of this petition is Dr. Siham Benchekroun, a Moroccan novelist and academic. It is an early Sunday evening and her voice over the phone sharply contrasts the five minutes of prerecorded introductions in Arabic that precede it.

“The family law affects everyone, but no one likes to talk about it.” When I ask her about women in Morocco who would be willing to attest to the effect of law on their lives, she is adamant. “People fear for their identities, because this is a taboo. No one likes to talk about it.”

Dr. Berraine agrees with Benchekroun: “It is only very recently that this topic has become debatable. A few years ago, civil society organizations largely avoided addressing the issue because it was considered too difficult an issue to tackle.”

Still, the protests and petition championed by Dr. Benchekroun indicate that some are willing to act. In fact, this recent unrest is almost identical to the beginnings of protests which led Tunisia, another Muslim majority country, to officially overturn its own version of the Ta’sib, due to the way it disproportionately allocates inheritance based on gender.

However, Dr. Tajeddine, a Moroccan supreme court lawyer and diplomat, explains that the process for change in Tunisia and Morocco goes through very different hurdles, especially when it comes to laws derived from the Quran. In his grey suit, he leans back in his chair; behind him are towering bookshelves, empty except for a picture of him with the king, and a signed autograph from Neil Armstrong.

“It was possible for Tunisia to reform because the president himself led [the reforms]. It is more difficult in Morocco because the King is the head of the Ulema Council, and is known as the ‘protector of the faithful,’” Dr. Tajeddine says, smiling almost apologetically. “He cannot modify anything that comes from the sacred book.”

Still, Tajeddine clearly stands by his belief in Morocco’s progressivism and gender parity. He emphasizes that “women can be judges, lawyers, engineers, and even police in Morocco. Recently, women can even become religious notaries, a job which was legally restricted to men.”

“The legalization of rights between men and women is going very, very high. But, in Morocco we still believe that questions of inheritance are fixed into the Quran and that everything can be modified or changed except the Quran.”

The King of Morocco, Mohammed VI, seems to echo this sentiment. In his 2011 speech introducing the latest changes to the Moroccan constitution, which were hailed as progressive, he reassured conservatives with a reminder that he would not “legalize what is forbidden.” Tajeddine claims this is reason to believe that regardless of how far Moroccan society liberalizes, it will be the last to do away with the inheritance law and any other provisions explicitly laid out by the Quran.

According to Tajeddine, the best thing for families to do is find loopholes in the law. He shrugs, “somebody, before they are dying…can ask the notary to put title deeds in the name of the daughter, and put their children in a position of equality. The decision has to be made during the person’s life. The state imposes rules of law from the Quran if [the owner of the property] doesn’t do anything about it during his life.” However, for many Moroccan families that do not have an education or access to legal recourse, this loophole remains out of reach.

Liberal Islamic Preacher, Mohamed Abdelouahab Rafiki, suggests a different strategy. According to a Moroccan publication, the Conversation, Rafiki has publically argued that the only way to change the inheritance law is to change the way the Quran is read, through ijtihad, or reinterpretation by religious scholars.

With Moroccan society trending towards more progressive values, while the majority stands by Islamic law, it is not an unpopular belief to argue that reinterpretation can address any unjust inequalities created by Quranic law.

Ismail El Hailouch, a Moroccan international student and Economics major at Yale, mulls over whether the law should be reinterpreted. “I think that is a very hard question. The thing is that back in the days women were not expected to work, so it was justified for them to inherit less property. But I don’t think it is justified anymore, because women have the same duties as men.”

He explains that, along with many other school-age students in Morocco, he learned about inheritance law as part of Islamic education. “I have taken a class on it, but it was a lot of numbers because its application is very numerical and situations-based. If there is a son, and he has a sister, and she is married…it all affects the specific outcome.

Ismail says that “most people are neutral about [the law], they don’t discuss it as an opinion, but just take it as a fact.” He’s not wrong. A study by the United Nations High Commission for Planning (HCP) showed that “eighty-seven percent of Moroccans opposed gender equality in the division of inheritance.”

Bur regardless of whether the majority supports it, there is no doubt that inheritance actually plays a huge role in the lives of women. As Abdelhak Senna of the Conversation writes, “The issue of inheritance is fundamentally economic. By denying women access to inheritance–property and money–the law is helping to keep them financially dependent on men and vulnerable to male violence.” Without capital of their own, women are less likely to be able to start their own businesses, manage their own finances, or leave unhappy and abusive marriages.

This is even more applicable to women born into less privilege. Ismail says that “people in the lower middle class and below are very concerned with inheritance, so they are fairly educated on the topic.” To lower income families, inheritance determines livelihood, and is crucial for women who are already less likely to be employed or as educated as men.

My encounter in a Medina only confirmed this, as a woman in a deep blue hijab held up metal worked earrings that shined in the harsh sun. With English more marred by a lack of confidence than lack of skill, she told me that her name is Rehana.

Rehana was one of the only women working in the Medina as far as the eye could see in the swaying mass of people filling the narrow alley. She told me that she did not know much about inheritance, but did know one thing.

“I have to be able to take care of my family and myself.”

[hr]

Shreeya is a sophomore in Timothy Dwight College. You can contact her at shreeya.singh@yale.edu.