California’s drought is officially over. Its worship of water is not.

Story and photos by Robbie Short

[divider]

And it never failed that during the dry years the people forgot about the rich years, and during the wet years they lost all memory of the dry years. It was always that way.

—John Steinbeck, East of Eden (1952)

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s it happens it has been raining in California this year. Heavy rains. Constant rains. Rains that have filled the state’s reservoirs and watered its fields and even—because there has actually been too much water falling—damaged some of its dams and flooded some of its cities. This February, 180,000 people living in Butte, Sutter, and Yuba Counties evacuated when it seemed that the Oroville Dam, the second largest in the state, might collapse and unleash a 30-foot wall of water. In March, the Los Angeles Times warned that this year’s snowpack could flood downstream communities—many of which have already been inundated several times this season—once the snow melts. That article ran under a headline that included the words “flooding risk,” the irony of which would not have been lost on anyone familiar with California’s recent climatic situation.

This is a state five years into one of its most severe droughts on record. For two years California residents have lived under mandatory water restrictions, the first in state history. I grew up near Sacramento; I still remember clearly the photo that led the front page of our local daily, the Sacramento Bee, the day in 2015 that Governor Jerry Brown signed the executive order approving those restrictions, which slashed urban water use by 25 percent. In the photo, Governor Brown stands in a dry field in Phillips Station, the site of the California Department of Water Resources’ official snowpack measurements. It was April 1st; the Bee’s caption pointed out that, at that time of year, the governor should have been standing on several feet of snow.

This year’s snowpack, as of March 30, sits at 164 percent of average. Just eight percent of California now remains in drought, all of it moderate or severe (as opposed to “extreme” or “exceptional”). This time last year, 90 percent of the state qualified as drought-stricken under the U.S. Drought Monitor’s guidelines. Thirty-five percent qualified for exceptional drought status, the worst classification, which is characterized by widespread crop losses and shortages in reservoirs, streams, and wells severe enough to create “water emergencies.”

Farmers and other agriculturalists bore the brunt of the hardship during the dry years, as harvests shrunk and they were forced to let more and more fields go fallow. On the domestic level—which is to say the more publicized level—homeowners, city governments, and golf courses let their lawns go brown; people took fewer and shorter showers; and restaurants began serving water only after patrons requested it. Many of the people I met during my college admission weekends in April 2015, just weeks after Gov. Brown approved the restrictions, asked about the drought after I told them I was from California. A few of the “wittier” ones offered me water.

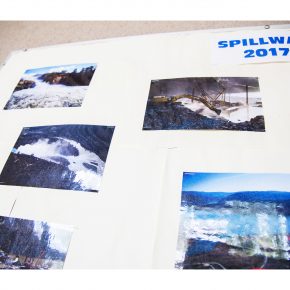

I get fewer such offers now. Even after the near-catastrophe in Oroville, it seems that fewer people are aware of California’s climatic situation today than during the worst months of the drought. Narratives of catastrophe tend to captivate more than do narratives of salvation. A few of my friends from home didn’t even know much about the Oroville crisis until I told them I was driving up to try to see the debris. Although the dam didn’t end up bursting, the engineers were forced to release water at such a violent rate that the primary spillway began to fail, at which point they opened the sluices to the emergency spillway for the first time since the dam opened in 1968. I had read that the debris in Oroville could cover a football field up to a height of 80 stories, and I wanted to see it.

For safety reasons, I could not, but I was able to see Lake Oroville from the other side and imagine its 2.6 million acre-feet surging through the suburban community I had just driven through. Standing a few feet from the water’s edge, looking across its wide expanse, I remembered the marquee signs and handmade posters I had seen along the road that read “THANK YOU DAM WORKERS.” They struck me as startlingly nonchalant.

Perhaps they shouldn’t have. This is a state, after all, where the most important political, economic, and social issue is and will always be water, and the control of it. From my dorm in Connecticut this April, I watched the press conference in which Governor Brown lifted the order that for three years had designated the drought an official state of emergency. “This drought is over,” he said, “but the next drought could be around the corner. Conservation must remain a way of life.”

Brown’s statement reminded me of something Joan Didion, one of the Golden State’s most prominent native daughters of the last century, wrote in 1977: “Some of us who live in arid parts of the world think about water with a reverence others might find excessive.” So it is in California, whether the rains come or not.

[hr]

Robbie Short ’19 is a History major in Silliman College. He can be contacted at robbie.short@yale.edu.