By Phoebe Campbell

Controversies over the rightful ownership of historical objects have affected countless museums and artistic institutions across the globe. These debates are generally a result of historical acquisitions, made during times when there was no legislation to regulate the exportation and display of foreign objects. Oftentimes, the preservation of these objects justified their expatriation. Each country and institution have their own methods to guarantee the fairness and legality with which objects are acquired, but there remain many examples that do not have a clear resolution. Few objects are the subject of such heated debate and protest as the Elgin Marbles, currently held by the British Museum.

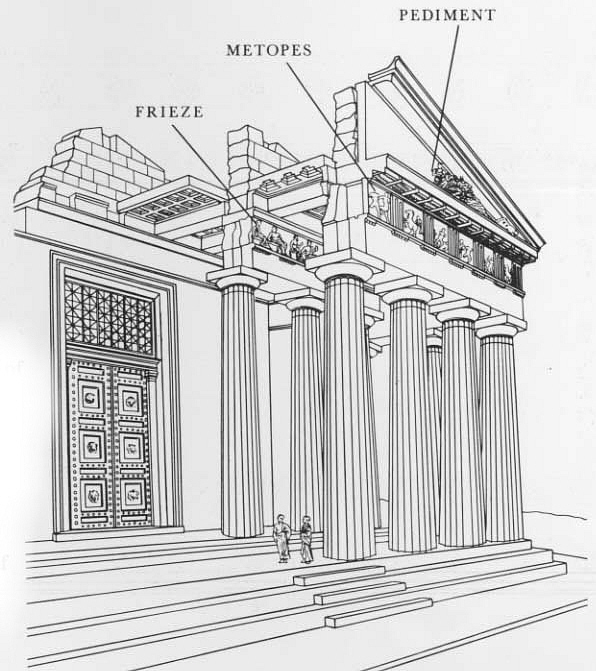

The “Elgin Marbles” is the name given to a collection of Parthenon relics taken from the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, to Britain between 1801 and 1812 by the seventh Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce. The collection is made up of sections of the outer decoration of the Parthenon. The construction of the Ancient Greek temple dedicated to the Pagan goddess Athena, the patron of the city of Athens, began in 447 BCE and was completed in 438 BCE. The 19th century saw a huge resurgence in the academic exploration of countries with rich archaeological history such as Greece, and excavated artifacts commonly accompanied the written descriptions and paintings created during these expeditions. Elgin’s stated aim for his expedition to Greece was to take casts and drawings of the sculptures from the Parthenon, but he soon began to remove objects from the Parthenon and its surrounding temples: the Erechtheion, Propylaia and the Temple of Athena Nike. The ‘marbles’ describe the sculptures taken from the frieze, metopes and pediment of the Parthenon, along with select sculptures from the other temples of the Acropolis, and are widely considered to form the culminating moment in Greek classical art and architecture. Those that reside currently in the British Museum’s Duveen Gallery were sold to the British government by Lord Elgin, and subsequently given to the museum.

Lord Elgin’s decision to remove the marbles had one significant advantage: it guaranteed the objects’ preservation. The sculptures are in excellent condition, in part because their removal from the Parthenon facilitated their protection from the elements and from vandalism. The Parthenon has had a history of violence since its original conception as a Pagan place of worship. During the Great Turkish War of 1683 to 1699, the Acropolis was heavily fortified by Ottoman forces and the Parthenon was used as a gunpowder store. In 1687 the building fell victim to a Venetian mortar, causing a huge explosion which destroyed much of the temple’s roof. This destruction was followed by further ruination in the form of plunder, as the site was stripped of many of the fallen sculptures. The British Museum has made a convincing case for their preservation of the integrity of the artifacts, given that many of the sculptures that remained on the Acropolis in Athens after Lord Elgin’s archaeological endeavors have considerably deteriorated in condition due to erosion. This argument has been strengthened in the light of the destruction in recent years of culturally and archaeologically important sites such as Nineveh, Nimrud and Palmyra by the forces of ISIS. The fact that Rooms 7, 8 and 9 of the British Museum, practically adjacent to the Duveen Gallery, house stone panels and reliefs from Nineveh and Nimrud lends considerable, if uncomfortable, weight to the argument that the museum as an institution can play a vital role in the preservation of cultural artifacts. It is an unavoidable truth that had those panels remained in Nineveh and Nimrud, they would almost certainly have been pulverized by the bulldozers of ISIS. In this light, the argument of preservation is a powerful one against accusations of appropriation.

While recognizing that the actions of Lord Elgin in the early 19th century have ensured the preservation of the marbles, there is an ongoing debate as to whether Lord Elgin had indeed obtained permission for removal of the marbles from the then governing authorities of Athens – the Ottomans. The argument for their continued residence at the British Museum has also been significantly weakened by the construction of the New Acropolis Museum in Athens, completed in 2009, directly below the Acropolis itself. Until this point, another aspect of the British defense of their ongoing possession of the marbles was the fact that the Greek government had no suitable space large enough to house the artifacts. The original 19th century Acropolis museum was architecturally modest, tucked under the brow of a hill just beneath the Parthenon. However, even after an extension was added following the Second World War, the museum could only have held a fraction of the sculptures from the Acropolis above.

The construction of the New Acropolis museum in Athens has very much neutered this argument, and the layout of the exhibition in the New Acropolis Museum makes a pointed comment directed at the British Museum’s own display. The Duveen Gallery mounts the sculptures facing inwards and at just above eye level, the exact reverse of their original positions on the Parthenon itself. The marbles in their original configuration would have lined the exterior of the building, facing outward, and would have been situated well above the viewer due to the temple’s colossal scale. Furthermore, the Parthenon sculptures which remained on the Parthenon site and are currently exhibited in the New Acropolis Museum are poignantly situated in a way that justly highlights the absence of certain sculptures. The sculptures surround a structure which recalls the form of the Parthenon itself. Dazzling white plaster copy sections of the frieze and metopes stand in stark and obvious contrast to the more weathered remaining original sections. In marking the missing original sections in this way, the museum makes clear that these are temporary arrangements. The spaces are effectively reserved for the objects currently held in London and elsewhere in the hope that they will be returned, and the various exterior sculptures of the Parthenon will be reunited once more. In an interview last year with the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea, the director of the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer, stated, “the Trustees of the British Museum feel the obligation to preserve the collection in its entirety, so that things that are part of this collection remain part of this collection,” despite acknowledging that there is a desire to see all of the Parthenon sculptures reunited in Athens. Ultimately, a mission which began with the goal of preserving artifacts is still a mission which deprives countries of key parts of their history.

These polemics are largely catalyzed by our concepts of ownership, which are often not straightforward. Paintings do not necessarily belong to whoever created them; they may belong to whoever has commissioned their creation. Someone who discovers or excavates an object does not automatically become its owner. There are similar issues surrounding works that are thought to be missing and resurface after a long period of time. Examples include Nazi era works that were stolen or hidden for some period during the Second World War and re-appear some time afterwards. There is often no record of their owners during this time and it is difficult to prove or refute a claim of rightful ownership when there is no official documentation pertaining to the object for a few decades. In these circumstances, legal proceedings aim to resolve the conflict and establish the objects’ rightful ownership.

While the Elgin marbles provide an early and notable example of issues of acquisition and ownership, much of the national and international legislation that has been introduced to regulate the acquisition of cultural property stems from more recent incidents of archaeological looting and trafficking. The 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property establishes a set of regulations to address the global problem of looting of significant cultural sites. Subsequently, legislation on a national scale has been implemented in countries around the world to reinforce UNESCO’s international mandate. In 2016, the US introduced the Protect and Preserve International Cultural Property Act, allowing them to restrict the importation of “any archaeological or ethnological material of Syria.” Such measures ensure the responsible acquisition of objects on a national and international scale, but the problem is not only one of acquisition but also of restitution. The 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects not only strengthens the restrictions on import and export of cultural items as set out in the UNESCO legislation, but also establishes a clear international legal framework within which the objects in question can be restituted or repatriated. Neither the US nor the UK have signed this treaty. In the UK, there currently exists no clear legal framework for the deaccession and subsequent repatriation of objects. However, the UK’s Museums Association has established a working group on decolonizing museum practice, and Arts Council England is revising its guidelines on restitution.

To ensure collections are built and maintained in a judicious way, the Yale University Art Gallery has implemented and continues to develop measures to ensure its standards for acquisition fall within legal and ethical guidelines. Antonia Bartoli joined the Gallery’s staff in January 2020 as Curator of Provenance Research and is currently assisting in the process of establishing a new Art Gallery Collections Management Policy, to be ratified by the Art Gallery’s Governing Board in July. Items in a draft of the policy are highly relevant to the controversy surrounding the Elgin marbles, including the requirements that “the object has not, to the knowledge of Gallery staff, been illegally removed from a historic or an archaeological site” and that “the object has not, to the knowledge of Gallery staff, been stolen or illegally appropriated (without subsequent restitution) from a previous owner, illegally exported, [or] removed from its country of origin without appropriate approval and documentation.” Such stipulations demonstrate that regardless of one’s stance on the legality of Lord Elgin’s acquisition of the marbles, the controversy they have created cannot be ignored. The controversy can, however, be used to inform the rightful acquisition of objects in museums and art galleries today. “Each acquisition is considered taking into account local and international legislation and American museum-standard guidelines,” explained Bartoli. “I consider legal and ethical matters, and advise on presenting facts – or in some instances, uncertain information – in the most transparent way possible. This and changing our pre-acquisition procedures are changing the Gallery’s practices for the better.”

It is of course more difficult when these legal proceedings concern not individual actions, or those of institutions, but those of countries. In the case of the Elgin Marbles, it is difficult to define who has the right to the objects, be it the British Museum, the New Acropolis Museum, the British government or the Greek government. The marbles have been safeguarded and displayed to the public by the British Museum for two centuries. The Museum’s position, according to their website, is that it provides “a unique resource for the world: the breadth and depth of the collection allows the world’s public to re-examine cultural identities and explore the connections between them.” The argument for the repatriation of the objects, and therefore the reason for which they form an example of appropriation, stems in part from patriotism and national pride.

The same could be said of the counterargument. After a leaked draft of the Brexit mandate implied that the European Union would insist on the return of “unlawfully removed cultural objects to their countries of origin,” the British government explicitly stated in February of this year that the Elgin Marbles will not be included in Brexit negotiations. A spokeswoman for the British government described the sculptures as “the legal responsibility of the British Museum.” This instance is one of the latest in a long series of attempts by groups and governing bodies to pressure the British Museum into returning the objects. Notable instances include student protests and performances staged in front of the Elgin Marbles displayed in the British Museum and a UNESCO offer in 2014 to mediate the debate between the United Kingdom and Greece. However, this offer was later rejected by the British Museum on the grounds that UNESCO works with governments, not museums.

It is interesting to note that while the British Museum has been subject to significant media coverage and pressure surrounding this issue, it is far from the only institution to house relics from the Parthenon. Other sections from the outer decoration of the famed Greek temple reside in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Vatican, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the National Museum of Denmark, the University Museum in Würzburg, and the Glyptothek in Munich. These examples are often conveniently overlooked in the media outrage directed at the British Museum, but they all play a role in the dispersal of Greek objects across the grand cultural institutions of Europe, a problem which the New Acropolis Museum and the Greek government seek to resolve.

The academic in me obliges me to set out, as I hope I have done in this piece, both sides of the argument. It is not straightforward and there are good arguments on both sides. As a schoolgirl growing up in a remote part of England, no trip to London was complete without a visit to the British Museum. More often than not, my steps were drawn left towards the Rosetta Stone and to the wonders of the Duveen Gallery beyond. However, in the summer of 2016, I walked around the reconstructed frieze of the Parthenon in the New Acropolis Museum and was dazzled by the beauty both of the original works and of their new state-of-the-art setting. Light-filled, yet shaded, as the original temple must have been, from the searing heat of the Greek August sun, the museum is framed with a long bank of windows looking out onto the parallel Parthenon high on the hill of the Acropolis next door. Even the bright white copies have a beauty in their own right and the overall integrity of the display has an ability to transport you back in time that a more conventional gallery space in west London cannot. The New Acropolis Museum creates a space with a superlative blend of aesthetics, sympathetic curation, and up-to-the-minute principles of conservation. Because of this, the solution posed by Greece to repatriate the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum, reuniting them with the artifacts that remain in Athens, is now in my mind the more compelling argument. Furthermore, I would argue that all of the Parthenon relics scattered across Europe should be returned. Such a reunification would serve to strengthen the integrity of Greek history and allow the country to show its pride and prowess in a way that is not hindered by historical imperialism. Regardless of the context of acquisition, neither property nor appropriation should fragment the preservation of a remarkable piece of human history whose magnificence we cannot truly appreciate so long as the sculptures remain apart. That, with genuinely the greatest respect for the dedicated custodianship of the British Museum to date, is my protest.

Phoebe Campbell is a rising junior majoring in History of Art and French in Benjamin Franklin College. She can be contacted at phoebe.campbell@yale.edu.