BY RACHEL BROWN

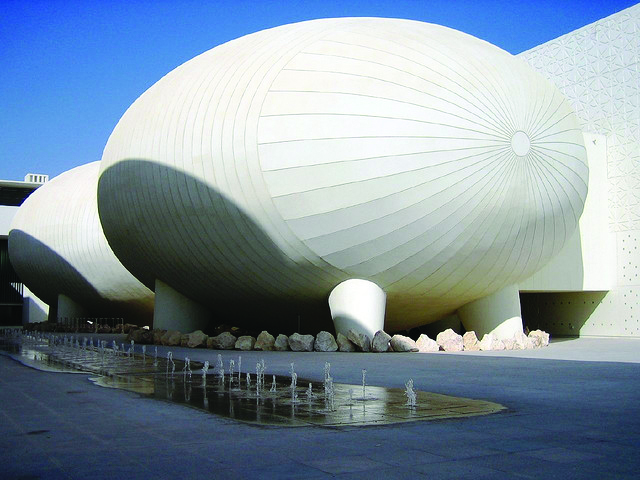

The view could have been torn from the pages of any American college brochure—students with notebooks lounging on an expanse of verdant grass, surrounded by striking buildings. But these buildings are not built of centuries-old ivy-covered stone, as in the cliché of Western grandeur. Instead, they are a sleek, futuristic blend of modern aesthetics and traditional Islamic architecture. Elaborate white latticework screens panel the walls of the student center courtyard and medical students attend lecture in white ovoid pods that resemble grounded blimps. The students’ heads are swathed in black hijabs, and the grass grows green thanks to heavy irrigation. In the middle of the Qatari desert, these students attend a university within Qatar’s “Education City,” a unique educational model now blossoming in the sands of the Middle East.

Education City combines numerous satellite campuses of different foreign universities—six American, and one each from France, Britain, and Qatar itself—on one 2,500-acre campus. Education City and a similar endeavor, Malaysia’s “EduCity,” reflect the modern reality that schools and the students that attend them can easily traverse borders.

The former began in 1998, when Qatar realized its economy wouldn’t run on gas and oil forever. According to the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development, the nation decided to begin a “journey from a carbon economy to a knowledge economy,” in order to provide future national economic security. Starting with the recruitment of Virginia Commonwealth University, Qatar began investing its abundant resource wealth into an education hub for the whole of the Middle East.

Through Education City, Qatar hoped to not only draw students from outside to study in Qatar, but also to reverse its troubling “brain drain”—the best Qatari students often went abroad for college and never returned. Now, rather than sending students abroad to America, Qatar is bringing American universities—including Texas A&M, Carnegie Mellon, and the Georgetown School of Foreign Service— to its students.

Universities participating in “education cities” in both Qatar and Malaysia are attracted by the opportunity to interact on a global scale and to increase their presence in regions with emerging political and economic importance. Everette Dennis, dean of Northwestern’s Qatari campus, explained that a critical factor in the school’s decision to expand overseas was the “desire to have a window into the Middle East.” It doesn’t hurt that the costs of satellite construction are largely underwritten by the Qatar Foundation, which was founded by ruling emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani; ten-year contracts eliminate most of the financial risks of expansion.

Malaysia’s aspirations are similar to those of Qatar. In 1995, nearly 20 percent of Malaysian students studied abroad, but overseas education was expensive and meant lost revenue from domestic tuition. To reverse these losses, Malaysia started its own kind of Education City – EduCity, where tuition will be significantly lower than tuition abroad. Construction on EduCity began in 2008 and the project’s main developer is Iskandar Investment, a partial subsidiary of Khazanah National, the Malaysian government’s strategic investment fund. EduCity officials invited predominantly British universities to set up branches in the city of Nusajaya, including the University of Reading, Newcastle University, and the University of Southampton. Malaysia was once a British colony, and its education system still retains traces of this colonial legacy. According to Tony Downes, provost of Reading’s Malaysia campus, the university, like Northwestern in Qatar, saw a campus abroad as helping his university gain global prominence. Setting up a school in Malaysia, Downes said, was “part of a strategy to increase international and global visibility.”

Economics are another key factor in the overseas college phenomenon: More and more international students demand and can afford high quality education, but may not be able to actually go abroad due to visa restrictions and other factors. Through satellite campuses, universities can meet this demand. Still, the schools claim they aren’t seeking financial gain in such pursuits—at least, not primarily. “The venture is expected to make a modest surplus in time, but the interest is reputational rather than strongly financial,” said Downes. But pursuing an international reputation is risky. The University of Reading’s Malaysia campus is the biggest development project in the school’s history, and it bears the same risks, reputational and otherwise, of any massive expansion. If schools spread themselves too thin in attempts to “globalize,” they could be reduced to brand names.

Domestic critics of satellite campuses, ranging from journalists to academics, fear that British and American universities cannot replicate the academic freedoms and fierce intellectual debate they foster back home. Qatar is a conservative society, with numerous religious and political sensitivities that must be considered. A current draft law, which has yet to be approved by the cabinet, would ban speech that could “throw relations between the state and the Arab and friendly states into confusion,” among other prohibitions. Malaysia has also been criticized by NGOs such as Human Rights Watch and Freedom House for maintaining repressive media and internet policies. Particularly controversial is the University and University Colleges Act, which prevents college students from joining political parties and restricts political speech. The exact specifications of how the Act will be applied in EduCity remain to be resolved, but it is likely that universities within EduCity will be subject to its provisions as well. Provost Downes also cited the challenge of introducing “the idea of questioning and challenging everything—including one’s professors” to some Malaysian students who have been steeped in a culture of learning by rote memorization.

Dennis, however, dismissed as “nonsense” concerns that the Qatar campus could tarnish the reputation of Northwestern. While he recognizes the complexity of navigating the fine line between local traditions and international standards on freedom of expression is complex, he also maintains that the entire endeavor is one “worth doing.”

Nikhil Lakhanpal, an American student studying at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service campus in Qatar remembers his concern over “taking the ‘Problem of God’ class with conservative Muslims.” But, he says, “the university [Georgetown SFS] has never backed down [with regards to unbiased teaching],” and the Qatar Foundation guarantees academic freedom within Education City.

Even with such guarantees, important questions remain regarding the degree to which schools in Education City and EduCity are able to achieve the same educational experience as their home campuses would provide. This question is complicated by the fact that satellite campuses in both Qatar and Malaysia are “niche” venues, specializing in certain academic areas; multidisciplinary education emerges only when all the campuses are viewed as a unified whole. To their credit, both education cities put students from different universities in shared dormitories. Additionally, students at Education City can cross-register for certain courses. But the focus of each school remains relatively narrow. Will simply using the same curriculum and teaching methods have the desired effect, or do curricula become imbued with new value based on the broader student experience? Dennis described his school’s campus in Qatar as “Northwestern with an Arab accent”—but at what point does education go from being spoken with an accent to being translated into something unrecognizable?

When campuses travel abroad, some aspects of the quintessential American college experience are inevitably lost in translation. Fierce rivalries over intramural sports and huddles of students working on problem sets in Education City, would be a familiar sight to American visitors, but the restrictions on girls entering boys’ rooms? Not so much. Lakhanpal explained that within the dorms of Education City there is “not as much of the dating, drinking, or ‘going out’ culture” as is found at most U.S. universities. Such behaviors might be considered distractions from the true purpose of education, but their absence undoubtedly alters the nature of the overall experience. For many Westerners, after all, university education is as much about learning how to independently navigate unfamiliar or awkward situations as it is about a professor’s lecture or discussions at the seminar table.

But campuses abroad also create unique opportunities for Western academics and students to gain a better understanding of foreign affairs and interact with regional groups in new ways. Universities joining EduCity hope it will provide a gateway for professors from the UK to collaborate with academics across Southeast Asia. Students and staff in Education City have witnessed the Arab Spring firsthand. Northwestern University in Qatar actually played a part in these events, hosting members of the Libyan National Transitional Council as they designed new rules for media freedom in their country. As the Middle East and Southeast Asia confront issues of religious and social freedom, higher education and its related ideas may turn out to be the most important Western exports in coming decades.

Lakhanpal also spoke of the Arab Spring: where else, he asked, would an American student have the opportunity to study alongside “the actual revolutionary youth of the Arab world?” Like the democratic uprisings that swept from Tunisia to Yemen, education cities are spreading across the Middle East and Asia. Even tiny Bhutan has introduced plans for such a venture. From the sands of Qatar to the jungles of Malaysia – and now perhaps to the mountains of the Himalayas – once-foreign ideals are effecting a new, educational, revolution.

Rachel Brown ’15 is in Saybrook College. Contact her at rachel.brown@yale