The Red Corridor: Tracing the origins and future of communism in India

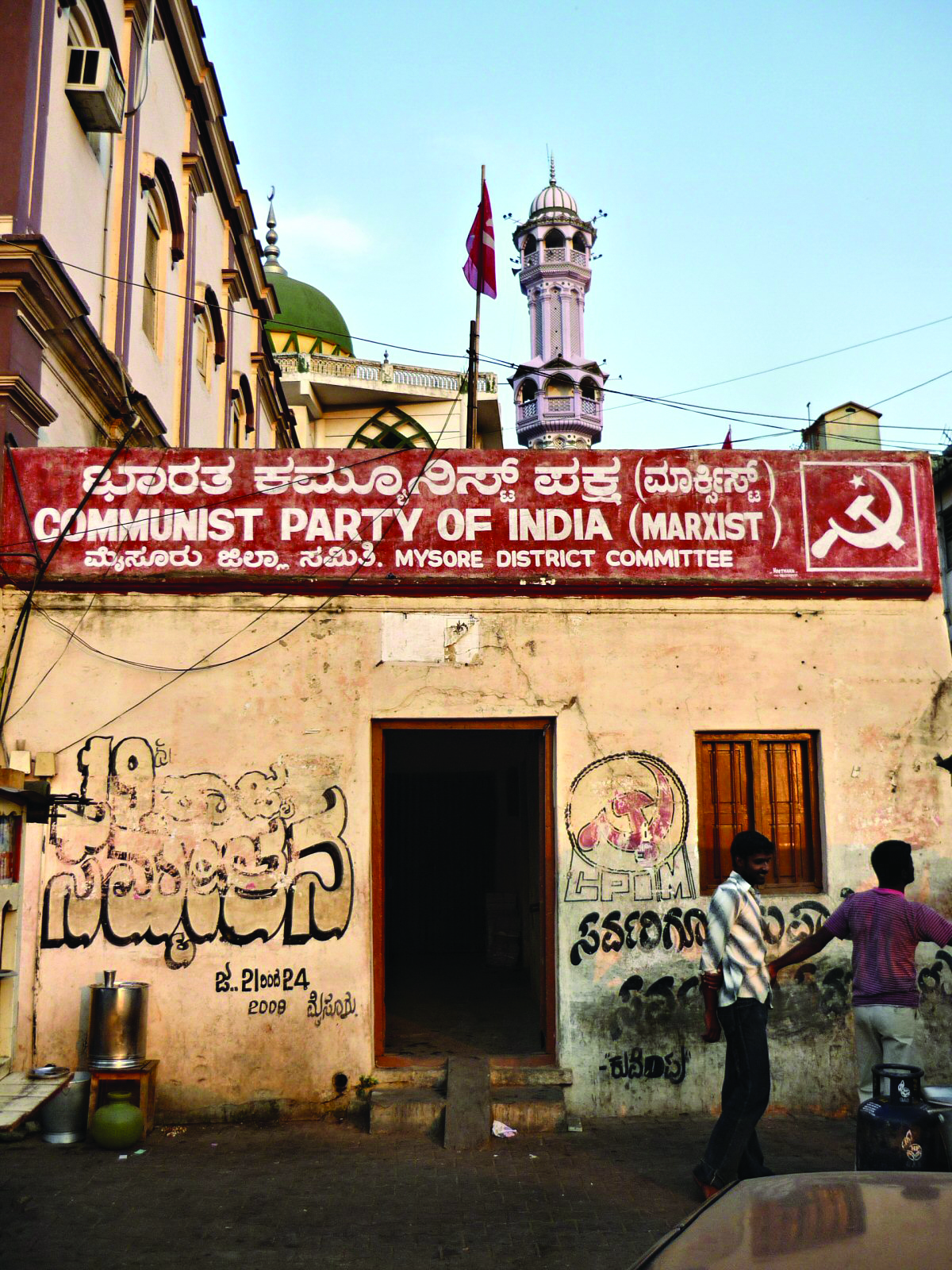

Above: A district committee building for the Communist Party of India (courtesy Flickr user runran).

[hr]

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n April 6, 2010, eighty officers from India’s Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and a small group of local policemen were killed in the deadliest assault ever by the Naxalite movement. “They seem to have walked into trap,” said Home Minister of India P. Chidambaram. In the aftermath of the attack, Kartam Joga, a prominent Maoist activist was arrested for allegedly planning the attack. In reality, his party had never condoned such behavior. Outcry from Amnesty International about the “fabricated” evidence surrounding Joga’s arrest eventually led to his acquittal. Yet, both the actions of the Naxalite movement and the Indian government’s misguided response illustrate the precarious political climate that more mainstream Indian communists must navigate today.

Citing such instances of violence, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi actively suppressed freedom of speech and had many political opponents arrested, especially those with any communist affiliation. In the face of unjust government tactics, the communist movement faced not only an uphill battle to gain legitimacy but also internal ideological divisions over how to respond.

As a result, in 1967, a segment of CPI(M) went on to form a more extremist, grassroots movement known as Naxalism, its name derived from an infamous peasant revolt in Naxalbari, West Bengal. That year, desperate peasants had taken up bows and arrows to protest oppressive landholder practices, only to be crushed by overwhelming police force. Their slogan of “Land for the Tiller” caught on among the educated youth of Calcutta. “The seventies was the decade of revolution [among] American campuses… French intellectuals,” recalled Civic Chandran. A former Naxalite, Chandran now edits an alternative journal on new social movements. “A young intellectual from a lower middle class, [I was] also attracted to revolutionary movements.” Through friends already involved, Chandran joined the underground guerilla movement, editing and publishing a literary magazine. In 1975, Gandhi declared a nationwide “Emergency,” claiming broad authoritarian power to rule by decree in order to crackdown on “internal disturbance.” Chandran cited the two-year long “Emergency” as inspiration for his radicalism; he was detained during the period.

Different communist movements quickly spread across what came to be known as the “Red Corridor” of India—states with some of the lowest standards of living in the country like Bihar, Chattisgarh, and West Bengal. Over time, however, government tactics succeeded in marginalizing Naxalism and the more mainstream CPI(M) to a few southern states. “In the elections following independence the CPI and the communists in general were a major political force, and would regularly come second in elections across the country,”said Tariq Thachil, an assistant professor of political science at Yale University whose research focuses on South Asia. “And then very quickly they were reduced to strongholds in West Bengal, Kerala and Tripura.”

In recent years, the political power of Left has further dwindled. In this past election for the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the Left could not agree on a single agenda or course of action. Unlike in West Bengal, where the CPI(M) dominates most elections, control over the state of Kerala regularly shifts between the Left and the more centrist Indian National Congress Party.

Thachil explained that “because of [the alternation in parties], it’s too early to say that CPI(M) is completely out of Kerala politics.” However, he added that in West Bengal there has been a lull after uninterrupted dominance, and that perhaps the party “is finding its way out.”

“Any kind of communism, including Maoism will not survive in India because India is different,” said Chandran. “[We have] to confront many identities and issues especially land, gender, caste, [and] nationality questions…”

There has also been rising discontent over the inability of Communist state governments to achieve tangible economic gains. For instance, Kerala’s CPI(M) has launched a massive and well-implemented redistribution and literacy program, achieving some of the highest male and female literacy rates in India. Yet the party remains largely unsuccessful in raising the overall wealth or average income within the state. “They are good at having the pie slit more equally,” said Thachil, “but less successful in growing the overall pie.”

Notably, there are also growing concerns over corruption within the Left, a faction that claims to have exemplary standards of honesty and economic justice. Last October, Samar Acharjee of Tripura, an official within the Communist Party, took a “funny” video with his friends where he laid in $24,000 worth of cash—a small part of the $110,000 USD he had gotten from government contracts—and joked about making enough money to create a bed of bills.

Inevitably, the video ended up going viral, and Acharjee was ousted from the party.

His actions stand in stark contrast to the behavior of model communist leaders like Manik Sarkar, popularly dubbed “the poorest Chief Minister in India.” Sarkar is considered the face of integrity in an otherwise murky political sphere. But perhaps it is this very sense of idealism that is to blame for the demise of the Left.

“People aren’t necessarily looking for a model,” said Narendra Subramaniam, an assistant professor of political science at McGill University, whose research also focuses on South Asia. “Some people are drawn towards anti-corruption and simplicity. Others are quite happy to go with fairly corrupt leaders like Jayalalitha, Mayavati, and the Gandhis as long as they feel parties are doing something for people like them. They are looking for patronage and beneficial policies.”

Ultimately, in order to keep up with in rapidly-changing economy, much has to be changed about the way the communist movement reaches out to marginalized individuals. Civic Chandran himself addressed this problem in highly controversial play, “Ningal Are Communistakki?” or “Whom did you make a communist?” Written in the mid-1990s, the play questioned whether mainstream communism was dedicated enough to fighting the patriarchy and helping the dalits, or those of low caste.

Chandran feels that Indian leftists must seek out a post-Marxist ideology. “Communism analyzed [the] industrial revolution and searched [for] an alternative, but the industrial revolution is over,” he said. “Marxists should learn from new young activists and update themselves to [address] the challenges of globalization age. Otherwise, I fear Marxists will [become] dinosaurs of the past.”

Vishakha Negi ’17 is a Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology major in Morse College. Contact her at vishakha.negi@yale.edu