By Marina Yoshimura

[divider]

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]ising temperatures are not the only symptoms of climate change. It also affects military operations, food security, and migration. Importantly, climate change is a security issue. The 2019 World Economic Forum in Davos highlighted the impact climate change could have on security, calling it a “threat multiplier.” CEO of the Planetary Security Institute and 2014 Yale World Greenberg Fellow Alexander Verbeek echoed these sentiments, stating that climate change is a “planetary security” issue, and that “at the end of the day, you need a holistic view on development [of climate change mitigation].” Adding security to the repertoire of our conversations on climate change is not only important, but also necessary to understand and address one of the greatest issues of our time.

It makes sense how the security efforts can affect climate change: whether a weapon is used a single time or two countries are engaged in a full-scale war, military operations can devastate the environment. The U.S. military’s carbon footprint, especially regarding CO2 emissions, is substantial. A single nuclear exchange emits 690 million tons of CO2 emissions, but even this single event, the Iraq war since 2003 has emitted 250-600 million tonnes of CO2 emissions. In 2012, the U.S. Defense Review published information on the correlation between water and security, issuing a warning that “As early as 2050, some low-lying bases along the U.S. East and Gulf coasts could be submerged for 10 to 25 percent of the year.” If countries promise to cut greenhouse gas emissions within the private sector while the U.S. Defense Department fails to assess and address its carbon footprint in the U.S. military, emissions will continue to beset the international community’s response to environmental damage and conservation. It could even, ironically, prevent military operations from running successfully. With rising sea levels comes major flooding, and if climate change continues at this rate, it would compromise military operations because they would need to readjust their operational strategies based on the environmental damage. They could lose access to the very places that make their operations effective. This could compromise human security.

The U.S. has already attempted to address this problem. Government-issued reports have warned the public that national security is at risk, inevitably threatening civilians as well. In 2014, the Department of Defense released a Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap stating that climate change poses “immediate risks to U.S. national security” to ensure that “mission readiness is not compromised in the face of rising sea levels, increasing regularity of natural disasters, and food and water shortages in the developing world.” However, no effective changes seem to have been made. In the past month alone, the U.S. military was forced to evacuate Parris Island during Hurricane Florence, and received devastating damage at Tyndall Air Force Base from Hurricane Michael. The later the U.S. military and the Defense Department implement measures to address such issues, the earlier the United States and the world will face consequences of climate change.

When the U.S. military addresses climate change, not only does it reduce CO2 emissions, but it also signals that it stands with the rest of the world in tackling global warming, a powerful diplomatic statement. (The U.S. military, given it is the most powerful defense force in the world, carries weight.) With President Trump denying climate change, calling it a “hoax,” the military’s voice can be the change the international community wishes to see. By analyzing its own carbon footprint, the military can better preempt environmental damage and disruptions to human security. If unaddressed, however, the military— and the planet— will face direct consequences.

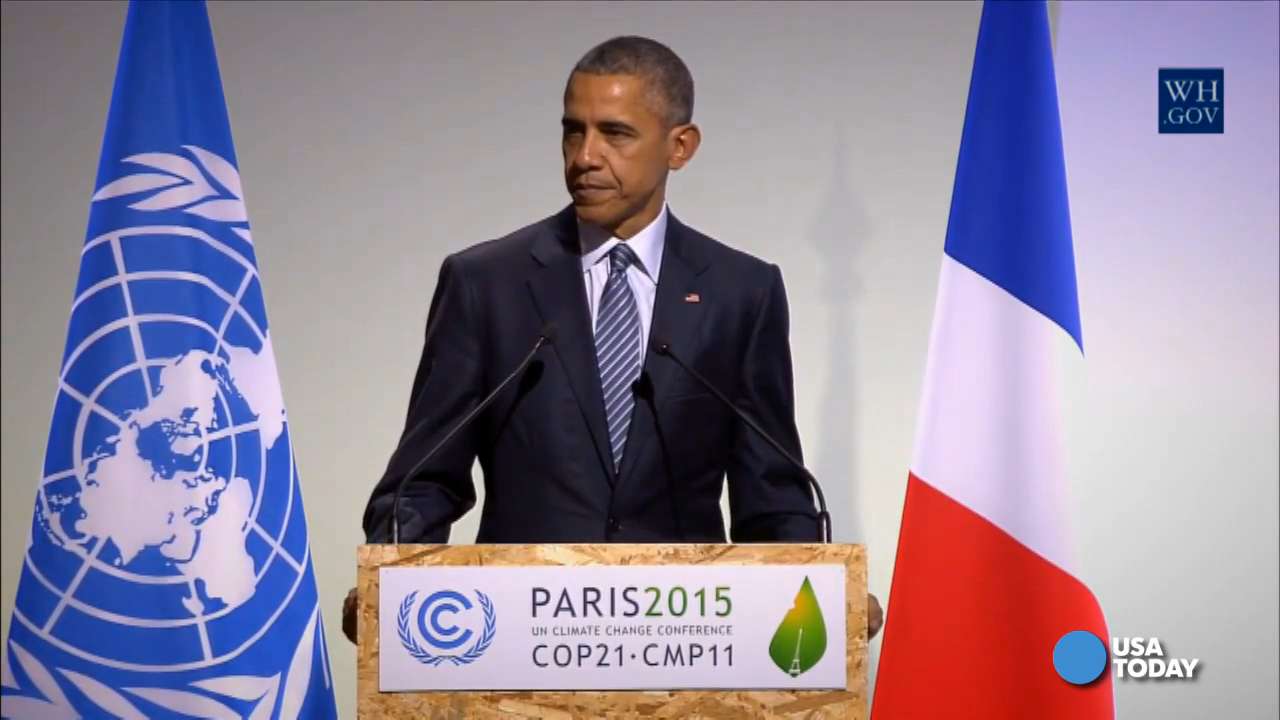

In the context of defense, legal frameworks can help pressure the U.S. government— in theory— to keep its carbon footprints minimal. The Obama Administration tried to mitigate the military’s impact on climate change by issuing an Executive Order in 2013. Executive Order 13653’s goals include, “building on these efforts, each agency shall develop or continue to develop, implement, and update comprehensive plans that integrate consideration of climate change into agency operations and overall mission objectives and submit those plans to CEQ and OMB for review.” Unless legally enforced, organizations would lack the incentive to follow through with commitments that could help staunch further damage to the environment and enhance human security.

Although the United States boasts the largest military in the world, it is not the only country responsible for addressing security in the context of climate change. Joint statements among countries enforce all member states to tackle security. For example, according to a UN Climate Change (UNFCCC) report published on October 14, 2014, heads of state taking part in the Wales Summit of NATO’s principal political decision-making body, the North Atlantic Council (NAC), announced that “climate change and increasing energy needs will shape the Organization’s future security environment and could significantly affect its planning and operations.” This announcement came at a time when the international community had already explored ways, such as conservation, to tackle environmental damage to little avail. Identifying other factors, such as security, that feed into the greater issue of climate change can help defense sectors address them effectively. Other sectors can hold defense sectors around the world accountable by capping their budgets or using universal shame as a tactic. When militaries around the world fail to reduce carbon emissions and other potential environmental damage, they put the people they are to protect—civilians, and even countries— at risk. But militaries are integral to the government, and isolating them would not be conducive to climate change prevention or preemption. Instead, the international community should issue formal warnings and implement sanctions to countries that refuse to align their defense measures to environmentally conducive methods.

Diplomatically a success, the Paris Climate Agreement falls short of enforcing security measures to prevent disruptions to human security. Verbeek says with the world’s middle class growing, the average population has become richer, which has led to an increase in consumption and a competition for resources. The lack of resources as a result of climate change, including food security, could lead to tensions and regional conflicts. Tensions among tribes and communities could then escalate into a civil war, creating and deteriorating fragile states. The problems are multifaceted, affecting security at personal, national and global levels. Verbeek’s organization, the Planetary Security Initiative of the Planetary Security Institute, brings together five institutions: The Clingendael Institute, the Hague; Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, the Hague; Adelphi, Berlin; Center for Climate and Security, Washington, DC; and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Stockholm. These institutions provide an agenda to address climate change from a security angle, collaborating with Foreign Ministries and UN agencies, merging its purposes to bring security to the forefront with other conventional methods of tackling climate change. Conferences and workshops help bring world leaders to discuss an issue that is not necessarily mutually exclusive but requires compartmentalization: national and individual responsibilities in addition to universal goals to address climate change. Institutions such as the Planetary Security Institute are necessary to fill in the cracks of international agreements that are effective in theory but insufficient in practice. They illuminate aspects of climate change that require further analysis and effort. Security is one of them.

Security is a major pillar of climate change and should be treated as such. Military operations both contribute and fall victim to climate change. Legal frameworks have demonstrated the U.S. Defense Department’s responsibility in addressing it. No matter how powerful the U.S. military, the United States is not the only country responsible for climate change, given the issue’s global significance. Diplomatically a success, many universal agreements fail to adequately address planetary security, food security, and human security in the context of the environment. In addition to reducing plastic bottles and sharing videos of dying polar bears, we, as individuals, would benefit from having conversations about security’s role in tackling climate change, and how climate change affects our security. After all, security can make or break one of the greatest issues of our time.

[hr]

Marina Yoshimura was a visiting student from Japan. She is the founder and Chief Executive Officer of The Quill Times, a student publication, and is a student at Waseda University in Japan. You can contact her at myoshimura@akane.waseda.jp