By Mahir Rahman

When your stomach calls, an easy go-to in Korea is a cup of ramen noodles, a dish just as popular among Koreans as it is among American undergraduates studying into the wee hours of the morning. At a traditional ramen house, you can be guaranteed that your ramen was made in wholesome pork-broth, a struggle that I (with my halal diet) faced while travelling through Japan. I appreciated that my Korean host mother, in lieu of pork, made ramen with fish broth and an ample servings of kimchi dumplings. The only struggle left was to survive the steam rushing into my face as I tried to get my fill.

Most weekends, I bought lunch on the go since I spent most of my time exploring other parts of Seoul and the rest of South Korea. Today, I wanted a little rest. A light repose. A lazy Saturday. I couldn’t move after the ramen. Mission accomplished.

With the warm ramen devoured, I mustered up the courage to have a heart-to-heart in Korean with my host mom. The language still remained a barrier but I wanted to see how far I could go. Last week marked a year since I started learning. My mother tongue of Bengali puts my mother to shame and my French got me kicked out of a boulangerie. Having a moment in Korean would be an astounding feat.

At the time, I only knew that my host sister was studying abroad and my two other host siblings, both married with children, did not live with my host parents. Except for the college years, the child of the house normally lives with their parents until marriage in Korea. At that point, I acted as filler in the typical Western structure of a nuclear family—a mom, a dad, and a kid or two. Why wasn’t there photo of the entire family hanging up somewhere?

Over the kitchen table, a wedding photo hangs framed on the wall. The photo actually dates back to less than two years ago. “사실 아버지를 삼년전에 만나서…” My host mom elaborated that she had only met my host dad three years ago.

I wonder if she heard the sound of glass shattering in my mind.

***

My parents separated in 1997. Over 11,000 miles away, my future host sister was also unaware of exactly what her mother was going through. Both of our families were going through hardship that made separation the better option. However, while my mom managed to get some support throughout the process, South Korea was ensuring that their single mothers were not. As common as separation and divorce already were in the United States, they just started to shake up households across Korea. These household changes stemmed largely from South Korea’s population control efforts.

Following the Korean War, population boomed in the pre-industrialized new republic. Most families lived rurally, earning a modest income through fishing and farming. Every helping hand, regardless how small, helped. The country’s available resources and economic capital could not support the ever growing population. South Korea started a national family planning campaign in 1962 in order to curb the population growth. After the campaign provided family planning counseling, contraceptives, and even abortion services, the fertility rate dropped from 6.0 children per woman in 1960 to 4.5 in 1970[1].

That wasn’t enough.

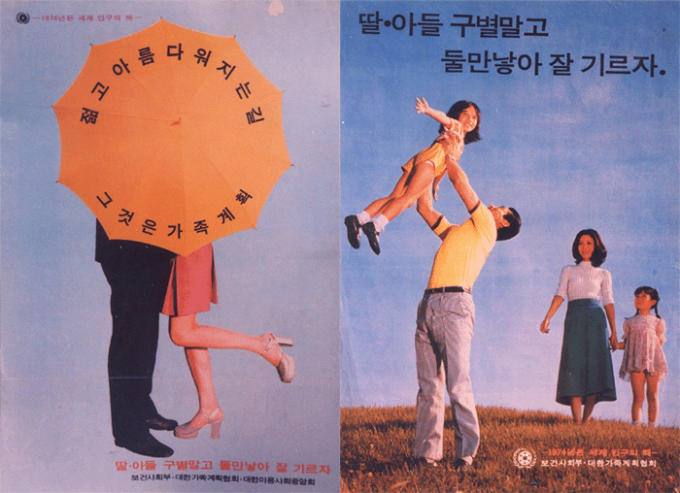

The South Korean government publicized their view of an ideal family. Both posters above exhibit a heavily used slogan in the 1970s, “딸 아들 구별말고 둘만놓아 잘 기르지”Don’t discriminate between girls and boys; have two children and raise them well[2]. The image ran counter to the traditional extended family of many rural Korean communities, where nuclear families lived in close proximity to their relatives. With the advent of industrialization in South Korea, these nuclear families migrated into urban areas for new economic pursuits. The movement helped control rural population growth and spurred urban industrialization, both of the government’s main priorities at the time. In the early 1980s, some campaign posters even started to consider two children as one too many because of continued population growth with slowing economic growth. In line with traditional views, certain posters started to glorify a family with a son over one with a daughter[3].

The modern nuclear family grew further detached from their relatives. Less intrusion by the extended families gave the nuclear family greater autonomy on how to run their household[4].

And whether they should keep it.

As women became better educated, acquired jobs, and focused on personal development, they started practicing more self-governance. Divorce laws also became more equal-handed, giving women, not just men, an opportunity to reconsider their marriage. Society backlashed quickly. Older generations held strong to traditional values and viewed divorced women as “disloyal” and “promiscuous”. Since marriage was viewed as the union of two families, divorce was seen as the disunion. Matchmaking agencies often ended up matching their new divorced clientele with each other due to the taboo nature of divorce[5]. With the shift away from the extended family and an increased interest in career development, population control spurred newfound independence for women and, for some, their divorce.

***

As divorce began changing social perceptions of women in the 1980s, most Koreans saw women that raised children on their own, particularly out of wedlock, as unfit mothers. Extended families would choose to not recognize these children as members of their own family. Status as a single mother would raise misconceptions of a woman among employers and colleagues. Married mothers would view children of single mothers as problem children, creating a school environment that reflected the discrimination single mothers faced[6].

My host mom lived in both worlds as a divorced mother. As she continued to work, she sent her daughter abroad first to Australia and then later to America for schooling. At the time, single mothers would cut ties with everyone they knew and start a new life outside of South Korea as a method to escape social discrimination. Single mothers that chose to stay in the country would hide their relationship status to avoid accusations. Some single mothers who trusted their own extended families had them raise their children[7]. Unfortunately, these methods do not always help single mothers escape discrimination.

When Shannon Heit, adopted by an American family, returned to her native homeland of South Korea on the 2012 season of “K-Pop Star”, her publicity helped her to reunite with her biological mother. But everything she knew about her adoption was a lie. Rather than being abandoned by her mother as her adoption company had stated, Heit’s mother actually left Heit and her sister in the care of their grandmother who sent them to an orphanage without her mother’s consent while she worked[8].

Luckily, my host mother was not forced into a similar position to adopt off her daughter. A typical Korean adoption occurs during the first months of the child’s life. In contrast, my host sister was at an age old enough to be well aware of her mother and their relations. For other single mothers, extended families would urge them to adopt off their child to save face. The government established adoption centers that doubled as single mother help centers. Nevertheless, any help given was focused on fulfilling the center’s primary purpose—adoption. The moment mothers debated on their own ability to care for their child, the agencies shamed them into giving up their child for adoption since “they would be better off with a family”[9].

***

But what is a family?

Just as that word continues to evolve in the United States, it is undergoing change in South Korea. Single mothers have fought back against discrimination. Choi Hyong-sook also experienced discrimination from her family, her adoption agency, and her country as an unwed mother. Ironically enough, she has received support from the by-product of this discrimination—adoptees. Adoptees and their foreign families helped her and other unwed mothers found Korean Unwed Mothers and Families Association (KUMFA). Through their efforts with partner organizations, Single Mother’s Day was established in South Korea in 2012[11].

Widening the choices available to single mothers beyond adoption and abortion is certainly a start, but numerous issues remain. One pressing issue regards the financial support of single mothers. Adopting families are provided with nearly twice the monthly stipend available to single mothers, providing financial support to the relatively well-off adopting families instead of the young unwed mothers without steady streams of income[12].

But the question remains: does the government have the right to classify what is an ideal family? It may no longer be advising prospective families that two children are one too many, but the government continues to paint an image of the family unit as a father, a mother, and a child. A less paternalistic and more empathetic approach could be to conceptualize the family as a suitable environment not just for the welfare of the child, but also for the well being of the parent(s) regardless of the size and makeup.

The government continues to treat the issues of abortion, adoption, divorces, single households, low fertility rates, and population stagnation separately. Irony exists between their discrimination against single mothers and disfavor of adoption. With the current fertility rate at 1.19 children per woman, according to the National Assembly Research Service[13], family welfare and development play critical roles in population growth. With overseas adoption decreasing but domestic adoption remaining uncommon, predominantly due to Confucian principles, fostering the idea of a single parent household could be the start to a population turnaround from stagnation to stability. The adoptee-formed NGO, Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea (TRACK) among others pushed for the Special Adoption Law (SAL). The SAL, established in August 2012, mandates unwed mothers who go through with their pregnancy to maintain custody of their baby for a minimum of a week before determining their fate. The mandate gives choice back to the single mother on whether or not she would like to raise a family[14].

The SAL is not without its flaws. Even though the amount of unwed mothers keeping their children is on a rise, another stipulation of the law has come under fire. SAL also mandates that mothers place their children on their family registry following birth, but adoption agencies are also allowed to make a registry for those children without one. Although the child’s name will be removed after putting the child up for adoption, Stephen Morrison, president of Mission to Promote Adoption in Korea (MPAK), argues such policy has caused the increase in child abandonment in South Korea since the law’s establishment due to the shame that comes with having a child out of wedlock. Public information on a registry can encourage unwanted scrutiny on single mothers. In Gwanak-gu, Pastor Lee Jon-rak built a “baby box” in 2009 so people could abandon their children in a safe microenvironment that alerts Lee’s church every time a new baby is placed inside. In 2013, 252 babies were abandoned in the baby box alone. Jane Jeong Trenka of TRACK attributes the rise in abandonment more towards the media coverage on abandonment and the baby box than SAL itself. One cannot help but wonder if a change to the registration process may resolve or augment the increasing abandonment and adoption issues[15].

Among OECD countries, South Korea currently ranks 3rd highest in divorce rates[16], a figure that may not bode well for newlyweds but certainly reflects the changing attitudes towards divorce. Furthermore, as high as the divorce rate is in comparison to both Eastern and Western nations, the ranking does not reflect the decade long decrease in divorce in South Korea. According to Statistics Korea, the divorce rate among married couples (divorces per 1000 married people aged 15 or older) has fell from the 2003 high of 7.2 to the 2013 low of 4.7, a rate that has been steady since 2010. The decade long decrease of divorces from 2003 has been the only one since 1982. If anything, South Korea’s growing acceptance of divorce as a right may be playing a factor in maintaining their marriages. The mean duration of marriage stood at 13.7 years in 2012, which has been consistently increasing from the low of 7.1 years in 1982[17].

My host mom endured several years alone, subject to the trials and errors of matchmaking. Here we sat, two years and counting into her second marriage and my host parents continued to talk to each other as newlyweds. All those years as a single mother, but things seem to have worked out well. South Korea seems to be having a change of heart. The ramen broth that remained in our bowls was no longer steaming. The sunlight that seeped into the room at the start of our conservation had already begun its exit. The cool autumn breeze made its presence known. Yet somehow, I still felt warm inside.

Mahir Rahman (’17*) is a Psychology-Neuroscience Major in Silliman College. Contact him at mahir.rahman@yale.edu

*Originally a member of the Class of 2016; currently taking a gap year in Seoul, ROK.

***

[1] http://www.jstor.org/stable/1965280

[2] http://thegrandnarrative.com/2012/02/16/korean-family-planning/

[3] http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2010/koreafertility.aspx

[4] http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-12278.html

[5] http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/21/world/divorce-in-south-korea-striking-a-new-attitude.html

[6] http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2014/03/05/single-motherhood-and-shame-south-korea

[7] Ibid.

[8] http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2014/0320/In-South-Korea-quest-to-recast-views-of-single-motherhood

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jean Chung for the International Herald Tribune

[11] http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/08/world/asia/08mothers.html

[12] http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20130916000681

[13] http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2014/08/25/2014082500859.html

[14] Refer to footnote 9.

[15] http://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2014/09/09/346851939/in-korea-adoptees-fight-to-change-culture-that-sent-them-overseas

[16] http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2007/05/117_2341.html

[17] http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/news/1/25/3/index.board?bmode