BY SAKSHI KUMAR:

When Raghuram Rajan – the former Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund – took the helm of the Reserve Bank of India earlier this month, he knew he was not in for an easy ride. With the rupee having reached its lowest closing level ever (of 79.922 rupees per US Dollar), and political mayhem negatively affecting the confidence of local markets, the Indian economy is currently lying in tatters. To complicate matters further, Rajan needs to make sure that his bid to resuscitate a once-booming economy does not neglect the disadvantaged and low-income segments of society.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has – not without controversy – traditionally given great importance to the processes of financial deepening and inclusion in order to prevent the marginalization of disadvantaged sectors of society. At the forefront of RBI policy have been the successful delivery of financial services at affordable costs, and the improvement in the overall volume of financial transactions to provide equal financial opportunity to all Indians.

To this end, in 1991, then-finance minister (and current prime minister) Manmohan Singh started revolutionizing trade policy to the extent that India’s markets started opening up to the rest of the world. Accompanying this change was a huge push for financial liberalization – which, rather unexpectedly, led to much greater financial depth in states with a widely-read newspaper industry. Unfortunately, there is very little intersection between the set of states with a prominent newspaper industry and the set of states in great need of financial deepening/inclusion – while opening up markets to foreign trade may have benefitted the economy as a whole, the poorest states experienced little to no change in economic development levels.

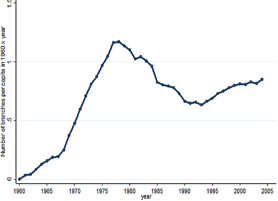

To further the efforts to improve universal financial service availability, a pre-liberalization RBI policy required commercial banks to open four branches in rural unbanked locations for every branch opened in an already-banked location. While this initially led to a massive boom in bank-branch penetration, this policy was bound to fail – after a certain period of time, saturation reaches such a point that it no longer becomes profitable to keep said branches open (see figure 1).

It is thus evident that previously introduced schemes that had some intention of increasing financial availability did not hugely benefit the lives of the underprivileged. Especially given India’s current economic climate, Rajan needs to ensure that the poor can also take full advantage of any expansionary policies he decides to implement.

Perhaps one of the most over-used phrases in current news media is that ‘India is country with great potential’ – but this does not mean that the phrase is false in the slightest. With a large number of students gaining degrees in STEM fields, an inexhaustible labor force, and an enviable pool of natural resources, there is no reason that India cannot mirror the astronomical growth of countries like China. Studies have shown that financial deepening can hugely benefit the self-employed in rural areas – if the RBI takes it upon itself to tap into the potential that India has, it could well find itself lauded for the reason India might be on its way back to the top.

Sakshi Kumar ’16 is in Davenport College. She focuses on public health and micro-finance in developing countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Contact her at sakshi.kumar@yale.edu.