How the government’s elephant conservation efforts do not align with its corruption in the ivory trade

By Amanda Mei

[divider]

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n a country ostensibly devoted to saving elephants, four police officers in Kenya were arrested Feb. 29 for selling illegal ivory from a government-owned car. Charged with possessing 11 pounds of ivory worth roughly $5,500, the men were only dealing with a small amount of illegal ivory compared to the government’s stockpile worth $270 million worth.

Only the latest instance of Kenyan government corruption, the crime ironically comes after the government’s announcement of a plan to light its stockpile of illegal ivory on fire. According to President Uhuru Kenyatta, government leaders will preside over the burning of 120 tonnes of ivory in what will be the single largest destruction of illegal ivory by any nation in history. The spectacle is supposed to demonstrate Kenya’s devotion to stopping the illegal ivory trade and saving African elephants. It will conclude a two-day summit on uniting African nations in the conservation of endangered species. But small acts of corruption by officials such as the convicted police officers threaten to undermine these broad conservation efforts.

Kenya’s Problem with Poaching

[dropcap]3[/dropcap]3,000 African elephants are still poached each year for their ivory, according to conservation group WildAid. Three quarters of all elephants on the continent have been slaughtered in the past decade. One fifth of the elephants have been lost in the past three years, according to the Los Angeles Times. Representatives of the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust say the African elephant might become extinct by 2025.

The problem is particularly severe in Kenya. The Kenyan Wildlife Service (KWS), a state-run conservation agency, reported 466 poachings between 2012 and 2014 in Kenya alone. The Kenyan Wildlife Service will burn the government’s ivory stockpile in April, and its grand mission is to “save the last great species and places on earth for humanity.” But conservationists doubt KWS’s reported figures. Paula Kahumbu, a wildlife advocate at National Geographic, puts the number of illegal poachings of elephants in Kenya at 10 times the corporation’s estimate. How much of the illegal ivory trade is being concealed behind the promises of the Kenyan government?

The answer is uncertain. But the Kenyan government continues to maintain its façade of support for elephants and conservationists. Even after last week’s corruption scandal, KWS spokesman Paul Udoto said in an interview with the International Business Times the KWS dealt “firmly and without prejudice” with government officials embroiled in illegal activities. The Kenyan Minister for the Environment, Judy Wakhungu, also projects optimism about the ivory situation in Kenya. Although the country was designated one of eight deeply implicated in the illegal trade by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species in 2013, Wakhungu said in an interview with the Daily Nation that Kenya was on its way out.

The Dichotomy of the Kenyan Government

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]ndeed, Wakhungu has seen several policy changes during her term of office. Kenya has taken measures to curb both the supply and distribution of illegal ivory. For example, fines for illegal poaching have increased from $300 to $200,000 to protect elephants in game reserves. The government has also introduced guard dogs to sniff out ivory in Kenya’s ports and forensic testing to trace and date illegal ivory.

The nation also hosted the first international conference on ending the illegal ivory trade. Organized by the Lusaka Agreement Task Force on Feb. 11, the meeting aimed at building cooperation between various African wildlife authorities. Leaders from Ethiopia, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, as well as members of the United Nations and Interpol attended the conference. Wakhungu represented Kenya at the event in her nation’s capital.

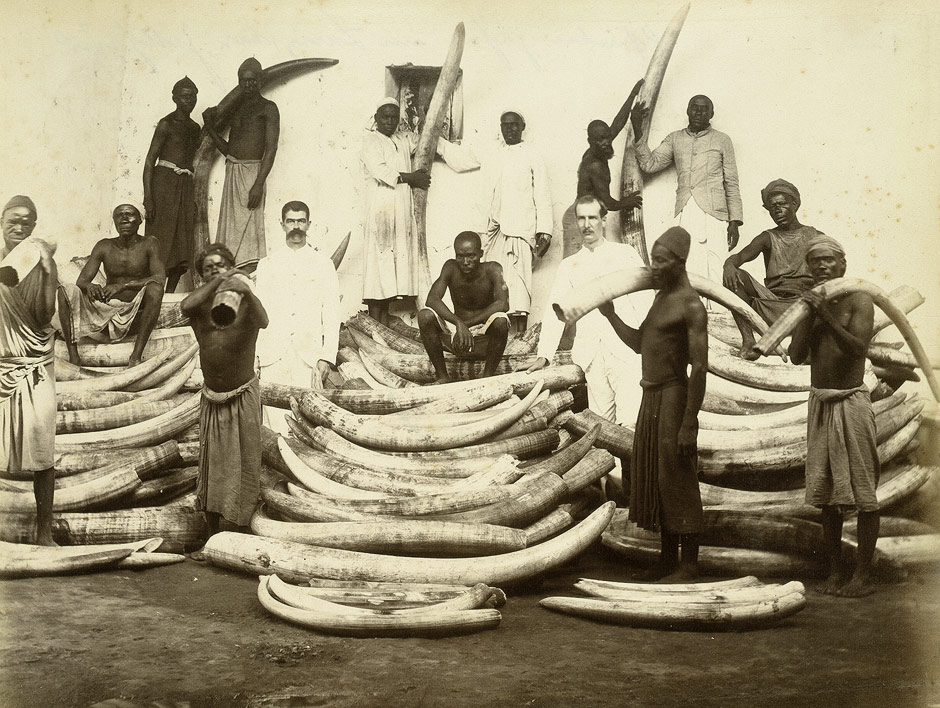

But these measures — policy changes, international conferences, and a plan to burn illegal ivory stockpiles — are largely symbolic. Despite Wakhungu and other Kenyan official’s apparently good intentions, Kenya continues to be a central port in the convoluted network of illegal ivory traders. Governmental corruption allows massive quantities of ivory to pass through the gates of Kenya. In Aug. 2015, the KWS reported 25,000 pieces of ivory weighing roughly 300,000 pounds in its stock. More ivory piles on each day. The 11 pounds of illegal ivory seized from police officers last Monday was the latest small increase in the Kenyan government’s stockpile. But these isolated exposures of governmental corruption fail to capture the entire problem — because the Kenyan government both perpetrates and prosecutes wildlife crimes. Some people who work in the illegal ivory trade also work for the government, and they own amounts of illegal ivory adding up to a significant amount. These people are sometimes caught by other government officials. The officials then seize ivory for addition to growing government stocks. But how many government officials who own ivory are caught? How much of their illegal ivory makes its way into the government stockpile? And how can we trust the Kenyan government to tell us how corrupt it is?

Conclusion

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]urning 120 tonnes of the stockpile in April may undermine the illegal ivory trade by removing some ivory from circulation. But to what extent is burning ivory just a show meant to appease conservationists and wildlife advocates? Fire may highlight the Kenyan government’s supposed devotion to the cause of elephants and their tusks — but it might also destroy evidence of governmental corruption.

Amanda Mei is a sophomore in Berkeley College. Contact her at amanda.mei@yale.edu.