The Problem With Judith Butler: The Political Philosophy of the Movement to Boycott Israel

By Hannah Flaum

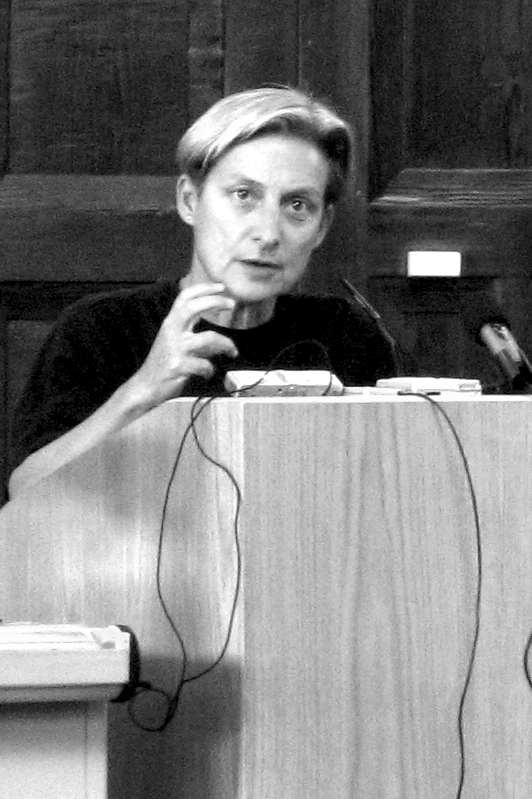

On Monday evening, Cary Nelson, Professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, addressed a group of New Haven residents and Yale University students and faculty in his talk: “The Problem With Judith Butler: The Political Philosophy of the Movement to Boycott Israel.” Butler is an American philosopher who recently expressed her support of the boycott of Israeli institutions because of their violations of academic freedom. Nelson, in response to Butler and those who share her support of the Israel boycott, exposed what he believes to be flaws in Butler’s rationale. With the movement to boycott Israel gaining steam recently, Nelson’s talk was both highly topical and controversial.

In his opening remarks and throughout his talk, Nelson emphasized that he believes Butler is earnest and sincere in her beliefs and also complimented her work in philosophy. However, despite his respect for Butler, he questions the legitimacy and the functionality of her Israel boycott resolution. For example, the boycott resolution will deny Israeli university faculty the use of Israeli university funds. Although Butler assures the protection of academic freedom by allowing the faculty to use their own funds for travel, Nelson explained that most Israeli professors do not have the financial means to do so given their relatively low salaries. Additional obstacles Nelson cited included inter-institutional research projects funded by universities as well as grants administered by universities. In reality, academic freedom protects the right to seek infrastructural support, but it does not ensure that infrastructural support will be provided.

Among his greatest criticisms of Butler is her deployment of an abstract concept of justice. He asserted that Butler avoids serious reflection of what would constitute political self-determination and that the Israeli and Palestinian conceptions of sovereignty are mutually exclusive and require the other to concede their demands. If peace is to be achieved, both Israelis and Palestinians must relinquish some demands designed to favor one party exclusively; everyone must settle for less than what they believe justice entails including territory. Nelson argued that Butler gives an unqualified endorsement of the right of return for Palestinians based on her abstract concept of justice and that she wrongfully denies the legitimacy of Israel’s claims.

A second criticism of Butler is her minimization of anti-Semitism. Nelson claims that this minimization effectively denies that anti-Semitism may – as Nelson argues it does – represent a deeply seeded hatred and conviction against Jews. Nelson claimed that “in the end, only one thing makes it possible to isolate Israel from other nations: anti-Semitism.” Anti-Semitism makes Israel “othered.” Although some academics suggest that claims of anti-Semitism are used as a tool to debunk any opposition – legitimate or not – to Israel, other academics express the belief that anti-Semitism is a justifiable argument against certain anti-Israeli claims. He explained that anti-Semitism is expressing itself in the way in which many American Jews, especially those that are younger and more assimilated, are overwhelmingly abandoning their heritage for acceptance given the negative judgments of Judaism and the Israeli state. Nelson noted the irony in criticisms of Israel, especially from the United States, because all current criticisms of Israel can be compared to the United States’ actions at various times throughout its history.

On a note related to anti-Semitism and its complexities with regard to the Israel-Palestine discussion, Nelson explained that rational arguments against Israeli policy do not constitute hate speech. However, he also argued that the problem with Butler’s intents and unqualified rejection of the Jewish state is that outrage becomes pointed against Israel’s right to exist rather than Israeli policy. Butler, in Nelson’s opinion, does not give Israel the credit nor the legitimacy it deserves. She sees the conflict as one-sided, rather than two-sided and sees only the justness of Palestinian claims. She believes that a fully ethical Judaism would reject the entire Jewish state. For Butler, there is no valid case to be made by Jews for the Israeli state. She provides no basis for negotiation or compromise, but only for Israeli capitulation. Despite Butler’s beliefs, there is no nonviolent way to transition to her “boycott resolution fantasy.”

Nelson concluded his talk by referencing what he claims are Butler’s abstract concept of justice and her deference toward Palestine. He also defined Butler’s hopes for a single state achieved without violence as a “mockery of nationalism” that are at best naïve and at worst extremely dangerous.

Hannah Flaum is a junior in Ezra Stiles College. Contact her at hannah.flaum@yale.edu