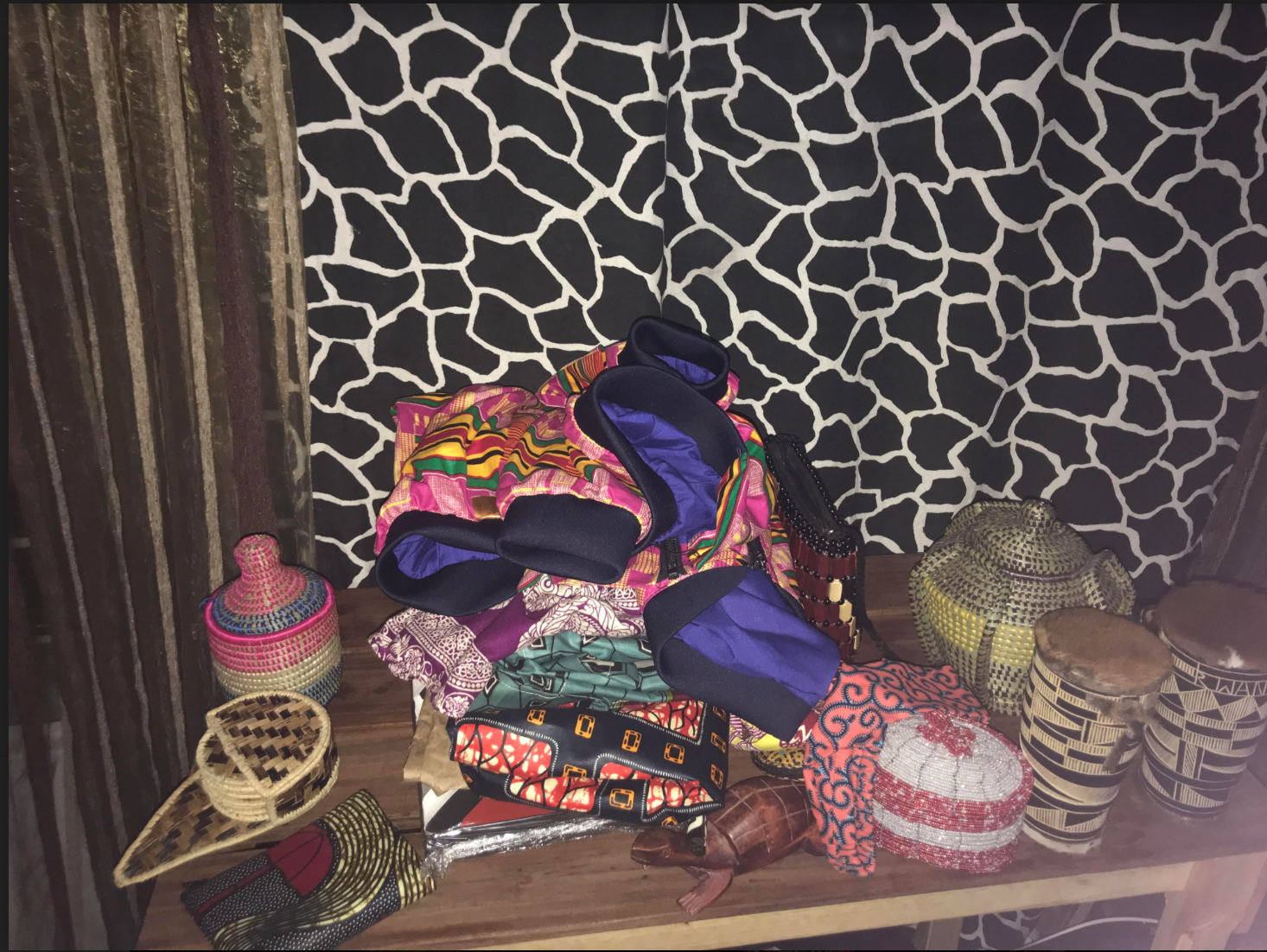

Featured image: The unfortunately large pile of things I acquired from the market.

[hr]

By Ileana Valdez

[divider]

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n Rwanda, markets are places where you can acquire anything from a mop, to tonight’s dinner, to a handmade evening gown. Having heard stories of the Kimironko market and its traditions of intense bartering, I fantasized about all of the gifts I could buy for my family members. To me, the market seemed like a challenge, an opportunity to argue for the best price, for the best product.

During a team meeting the night before about visiting Kimironko Market, I was excitedly describing the stalls filled with countless trinkets and handmade goods to my friends when a fellow hostel-resident stopped me. He said, “Remember, to you the market is a game but to the stall members it’s their livelihood.” My perspective changed. As I walked through the market I stopped thinking about how many relatives I could buy gifts for but about what each purchase meant to the vendors I was interacting with.

Unable to hide my American appearance, I was immediately swarmed with an overwhelming fleet of vendors trying to get me to come to their stalls. As I moved through the different stalls, I met vendors who had dropped out of college, vendors who taught English during the week, and seamstresses who were the sole breadwinners of their families. Although every vendor remained focused on their shared goal—to sell me as much as possible—they all had unique stories and backgrounds that they shared to keep me parked at their stalls.

[divider]

Kabebe, my Rwandan friend who helped me translate the stories of the market vendors.

[divider]

One particular vendor stood out. His name was Moses. He had started off going to school at the University of Rwanda but quickly realized the ever increasing amount of debt he would have to pay off after school. Suffocating under the pressures of finding a job after graduation simply to pay off the debts, Moses decided to become a businessman. With the help of his parents, he opened a stall in Kimironko Market and with his perfect English, had no trouble enticing foreign tourists towards his booth.

Over the course of a week, I would come to visit the market three times. Each time, I’d recognize more faces and learn more stories. By the last visit, I’d realize how community-oriented and cooperative the vendors were despite being competitors. I remember stopping by a booth to look at bomber jackets but not finding the pink fabric I wanted. Immediately that vendor, a woman named Sharon whom I began to consider a friend, helped me find a booth that did sell pink and helped me barter the price down to what she claimed was fair. Moses did the same.

In the same way the vendors would help each other gain customers, they’d also help each other reach maximum market prices. When one of my friends bought a jacket for $17000 RWF ($18.71 USD), the vendors refused to negotiate to a price lower than that, with any member of my party despite having offered the same jackets for $13000RWF ($14.31 USD) the day before. They had followed us as we walked through different stalls making sure no one got short changed from the maximum market price. Their tactics worked; I caved.

[divider]

The sewing station where many of my cloth goods were stolen. The cloth there is for my dress.

[divider]

The Kimironko market was a great place to make friends, to learn stories, and to gain confidence through bartering. The market was a place where I spent way more money than I should have, but each purchase was worth it. With every purchase came a new friend, a new person to help me navigate the Kimironko maze, and a new person to text on WhatsApp just to say hi.

Ileana Valdez is a junior in Pauli Murray College. You can contact her at ileana.valdez@yale.edu.