BY PHILLIP WILKINSON

Beijing’s air quality is appalling. Before I left for Beijing, many people warned me about how severe the pollution was, but I resigned them to over exaggeration. I thought it would only be a few days out of the year when the pollution would be really noticeable. It wasn’t exaggeration, however, because even on the best of days, a thin layer of contamination is visible, mostly from the mammoth quantity of automobiles in this city. It tends to ware on my general morale, especially after growing up under the clean, blue skies of Albuqueruqe, New Mexico. According to this New York Times article, “[China’s] Ministry of Environmental Protection revealed that air quality in Beijing was deemed unsafe for more than 60 percent of the days in the first half of 2013.” Unless this problem improved, I would not want to move back to Beijing in the future.

Another article I read offers an inside look into the opaque party politics in China, especially relating to the recent Bo Xilai scandal. Mr. Bo, who had a family history of high-level party membership, was an up and rising star amongst the “New Leftists” within the Party. The leftists lauded him for cracking down on organized crime in the city of Chongqing and his implementation of Maoist-style campaigns to revive “Red Culture” by championing Maoist quotes, revolutionary television programs, “red” songs, and youth moving to the countryside in search of work. Despite his fight against crime, however, he turned out to be one of China’s most corrupt party officials, being charged for, among other things, eavesdropping on past President Hu Jintao, and covering up a murder. Mr. Bo was relieved of all of his Party posts in part due to his corruption, but also because of a factional struggle within the Party. He had had his eye on the premier position within the Party for while, which made Xi Jingping’s camp uneasy. Yet, According to the China Daily, China’s flagship news source, Mr Bo’s indictment was a “credible demonstration that all people in China are equal in front of the law.” In reality, as the linked Economist article states, “It is just the latest evidence that some are more equal than others in front of a legal system that does the party’s bidding. Mr Bo is paying the price not for his undoubted crimes, but for having come off worse in a factional struggle.”

This kind of manipulation of facts is very frustrating to read about. On principle, it’s cowardly of the government to shield its population from understanding its policies by censoring social media, spreading pro-government propaganda and contorting the verbiage of news. This is one of the ways the Chinese government maintains stability, though. I wonder what long-term effects this kind of policy has on citizens’ moral characters and their ability to think independently? As the economy begins to slow down far off in the future, and more and more Chinese become educated, for how long will this method be sustainable?

Chinese people are taught from a young age to respect hierarchy. I was talking with one of my teachers who worked at a company in China and then moved to America to teach Chinese at Harvard. She said the two countries’ work environments are completely different. In America for instance, she can joke around with her boss without any problem. In China, she would never dare to do such a thing. In China, lower-level workers would never expose higher-level workers’ errors, when in America, the ability to freely admit error is seen as a positive character trait; it demonstrates humility and confidence in one’s own knowledge base. The Chinese are constantly attending to each other’s “faces,” or reputations. As a rule of social etiquette, one should never force another to “lose face” through embarrassment or acknowledgement of error. The way the China Daily is forced to report on the Communist Party reminds me of the losing face concept on a grand scale. The government never wants to be exposed publicly in a position of weakness or embarrassment.

While some of my teachers are willing to critique the government and share their points of view, others seem more influenced by government propaganda. These teachers have been taught to discredit Western media’s legitimacy. For example, the government disseminates the idea that all of China’s 56 ethnic minorities live in perfect harmony, when in reality, many parts of the country are rife with cultural tension, especially in the Western province of Xinjiang. I shared an Economist article about governmental discrimination against the Muslim lifestyle in Xinjiang with one of my teachers, and she immediately wrote it off, claiming that it must be false. She refused to believe the government would discriminate against its people. This article, written by one of the world’s most highly regarded news sources, was simply reporting the facts, however, and towards the end of the piece relayed the following from a cab company in Khotan, Xinjiang:

“ [Cab drivers] could be fined 5,000 yuan ($815) for picking up passengers wearing face-coverings that reveal only the eyes. If they do so a second time, they could lose their jobs. He says his company does not employ men with long beards. Khotan residents say a deadly eruption of violence in the city in July 2011 was prompted by anger over restrictions on Islamic dress.”

Some teachers are willing to speak their mind. A few have explained how they hate the fact they can’t criticize the government or access certain books they want to read due to the government censorship. On teacher told me that she spoke out against the government on her Renren (facebook equivalent), and the next day, her account was disactivated. If she wants to criticize the government now, she has to say something along the lines of, “There is a country I love very much, but sometimes it does things I don’t like, such as [insert criticism here]. I wish it would stop doing such things.” She is thankful that at Peking University, her alma mater, she is able to access many censored books at the school library because they are purchased from Taiwan. Another Chinese friend of mine from Yale told me bloggers know ways to split up characters or use hidden meanings to avoid the sensors. Chinese have to be crafty in order to speak out against policies they disagree with.

When I was in China’s northern province of Inner Mongolia, I had the chance to speak with 3 well-informed high school students. Two were Han Chinese and the other was Mongolian. It was interesting to compare the affirmative action policies in China to those of the United States. In China, if you are ethnically Mongolian for instance, you automatically receive an extra 20 points on your Gaokao, China’s comprehensive college entrance exam. Although not all Han Chinese feel the same way, the two Han girls I spoke with felt this was discriminatory (the Mongolian student seemed complacent). This is similar to the way some Americans, depending on whom you speak with, feel affirmative action towards Black, Hispanic, and Native American students is unfair.

The most interesting part of our discussion, however, came down to the teaching methods used in Chinese high schools. I asked them what they learned about the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong. They told me they spent the great majority of their time memorizing the positive policies of the late Chairman. Negative outcomes of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution were largely overlooked. They told me that on their Gaokao, if they were to write about Mao in a poor light or discuss the negative repercussions of his policies, it is universally known that they would receive a zero on their test. I asked them how they found this out, and they told me it was Renren. Social media is the main fountain of information for Chinese who want access to uncensored stories and a glimpse into the way the government truly functions.

I love my teachers and many Chinese individuals, but I don’t love this system and it’s one I’ll be living under for the next few months. I want to call it my home, but it’s hard to when there are so many aspects I disagree with and there’s no way I, or anyone else around me can gather to protest it. I wouldn’t feel right protesting it anyway since it’s not my country, but I’m frustrated on behalf of all the bright Chinese who have to live in an environment that champions absolute conformity to government policies rather than individuality of thought. When I speak with Chinese youth, I am relieved to find that many know more about the complexities of their government than the propaganda alone states and are willing to criticize it in conversational settings. The frustrating part comes when we try to discuss how the system might change because it seems utterly improbable. The governmental bureaucracy is so entrenched, and, especially after the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, the ability to mass protest so restrained that influence on their government feels far out of reach. In addition, the Chinese economy is growing rapidly, lifting millions of people out of poverty. Therefore, people have little incentive to challenge a system that at least improves their life from a materialistic standpoint and provides stability. Discontent Chinese must resign themselves begrudgingly to tolerate a nanny-state, corrupt on many levels, because it continues to provide for them.

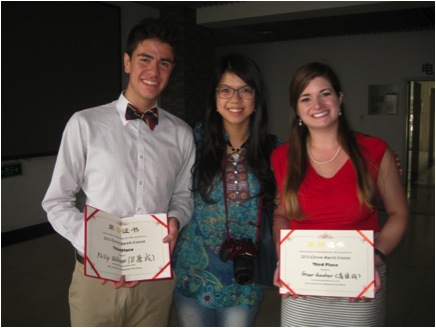

While I harbor many frustrations with the way this country is run, I don’t let this tarnish my vision of Chinese individuals who have been so kind and hospitable to me. Just last night, a Beijinger friend of mine from Yale invited me to dinner at his favorite Sichuan restaurant and insisted on treating me. All my teachers here have been incredibly supportive; I couldn’t have asked for more from them. I got a lump in my throat the night before my speech competition when eight or nine of them came over to my dorm at 9:30pm the night before the competition to listen to my speech and help me prepare. Although at first, Chinese may have a cold and shy exterior from many Americans’ point of view, they become kind, loving, and easy going once they get to know you. That’s been my experience with the youth here.

I will eternally miss HBA and China when I’m traveling next month. I look forward to comparing life in China to life in Japan and Singapore when I visit those two countries in a few weeks, but I’ll be reflecting on all my new friends and acquaintances from America and China alike. HBA is ending after 9 weeks, but I’m just beginning to scratch the surface of understanding this country, embracing its culture, and cultivating meaningful friendships with locals. My Chinese is improving everyday, but I feel fortunate to have a whole semester left to develop my Chinese ability and to strengthen my knowledge of this country. I had read a good bit about China before I came, but there are so many experiences that I’ve had and stories I’ve heard since being here that have enriched my vision of this place. That expansion of perspective can only happen through experience. The HBA chapter of my Life in the Middle Kingdom is quickly coming to a close, but I still have ample time left to see, experience, and grow. Next week I’ll be in Zhejiang province in the south of China teaching English to Chinese high school students in a small city a few hours to the south of Hangzhou with Yale’s Building Bridges. Stay tuned!

Phillip Wilkinson ’16 is blogging this year from Beijing, China. Contact him at phillip.wilkinson@yale.edu.