By Lucy Wang

[divider]

A couple of years ago, I read something that stayed with me—it goes something like this, “the more I learn about China, the less I realize I know about China.” That statement has certainly characterized my experience this summer. I’m here doing research about the role of art institutions and artists in Shanghai for my senior thesis. So I’ve immersed myself into the art scene, talking to artists, museum employees, curators, and professors in the arts field. But the more people I talk to, the more I realize that establishing a systematic view of China’s art scene might be impossible—since there’s not much of a system to distinguish between what gets censored by the government and what does not. There’s so much to delve into (so look for future posts about censorship in the arts, what artists think about the political situation in China, etc.) but for now, I want to talk about the construction environment and how that has impacted the arts in Shanghai.

I talked to one of first artists to move to M50 about the history of the place. Fifteen years ago, a group of three galleries and around ten to twenty artists moved to M50 after their old studios were slated for demolition by the government. M50 was a factory complex complete with warehouses and workers’ dormitories that went bankrupt in the 1980s after Deng Xiaoping (the Chinese Communist Party leader credited with overturning Mao’s economic policies) opened up the economy to foreign trade and investment and withdrew support for state-owned enterprises. Back then; it functioned as cheap artists’ studios, shared with small factories that rented out storage space. Now, rent has more than tripled as international galleries have moved it. Many local artists have since moved out to find cheaper studio space—not an unfamiliar narrative. The real estate around the area has boomed as well. The apartments in the background of the picture weren’t there fifteen years ago. Rather, they were storage houses built in the English occupational zone (after the Second Opium War, Shanghai was divided up into different foreign, residential areas). The artist mentioned that they were beautiful, and the M50 art community campaigned adamantly to keep them but to no avail.

This, unfortunately is also not an unfamiliar narrative. I talked with a professor of architecture at Shanghai’s Tongji University. She mentioned that Shanghai actually doesn’t need any more houses or new infrastructure. However, the government has immense pressure to keep building because much of its economic growth is tied to real estate development. And in China, the conception of private property is very, very different from that of the US. As a “Communist” country, all land is technically state property. Land ownership is never transferred to private individuals but rather, “loaned out” for a period of seventy years to individuals or fifty years to businesses. What happens after this period passes? We’ll soon find out as some of the oldest “private” properties will reach this point. Regardless, it is much easier for the government to confiscate land from people, demolish houses, and change whole neighborhoods.

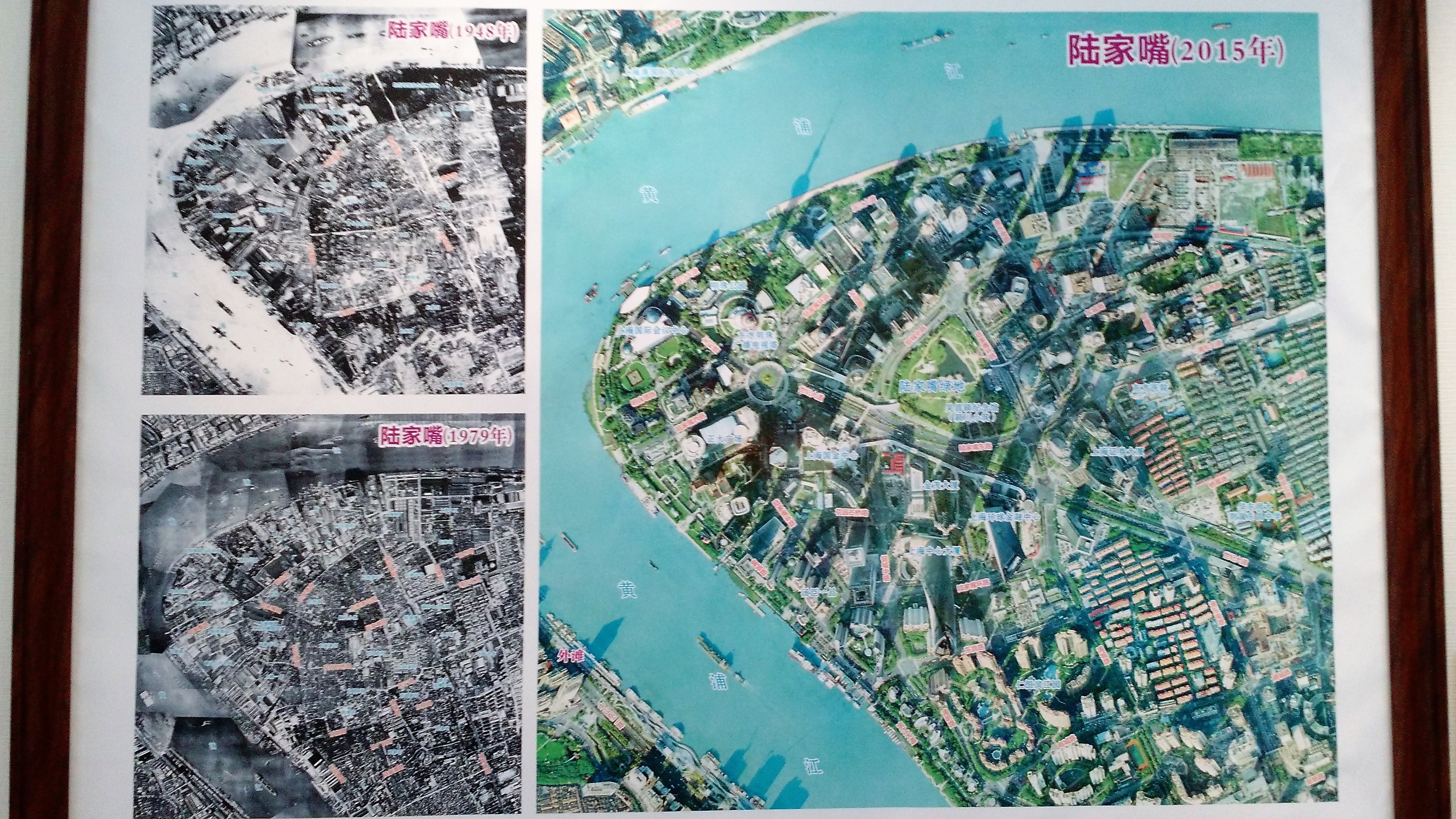

As you can see, Lujiazui, now the financial center of Shanghai (and really, all of China) and home to China’s tallest building (the Shanghai tower at 2073 ft), used to be a residential neighborhood. Where did those people go? The answer, oftentimes, is outside the city center. Though there are instances when a resident stands their ground and demands for a handsomely large amount of compensation for their property, the most common outcome is to be given a rather unsatisfactory amount of money, not large enough to stay in the city center and buy another apartment. As a result, these residents are forced from the city center to the city periphery without choice.

These two buildings are taken a block away from each other. The first was a residential neighborhood, the second is a cultural heritage street.

Development is not entirely the evil steamroller ruining residents’ lives that I’ve made it out to be. Some of the demolished buildings were indeed structurally unsound and outdated. But perhaps, I focused on the negative aspects because I want to give a voice to the people who told me the stories since they can’t be published in China due to strict censorship.

I conclude with two photos, that stand in juxtaposition to each other.

Lucy Wang is a rising senior in Morse majoring in Ethics, Politics and Economics. Contact her at lucy.x.wang@yale.edu.