Yale Greenberg World Fellows Interview Series: Jovitta Thomas

By Sophia Kang

Jovitta Thomas is a community development expert from India, specializing in development work in fragile and conflict states. In her over 20 years of international work, largely in the Balkans and Afghanistan, she focuses on helping new/ transitional governments design and implement very large development initiatives covering the sectors of local governance, poverty reduction, community development, conflict management, emergency support, and core public services. Her expertise is focused on implementing projects in highly volatile environments and adapting international best practices to local contexts.

What interests, experiences, or moments made you want to become a community development specialist?

To be very honest, I did not aim or plan to be a community development worker or specialist. As a teenager, I was more interested in politics and international relations. I was also raised in a Christian home where we were obliged to try to make the world a better place. This was at a time when my country of birth, India, was still classified as a “third world” nation. I hated that label and, with childlike faith, believed that if all of us worked together, we could achieve a better world for all. So I grew up dreaming of working for the United Nations (UN), an organization I believed had the potential to do just that and more. However, my first posting in the UN had largely to do with administrative work–procurement, logistics, financial management–none of which was what I had imagined international development would be. So I spent a lot of my free time volunteering in areas of my real interest.

I then got a break working with a team that was setting up the public administration of the transitional government of the then newly formed country of Kosovo. This work involved projects of monitoring its first elections and setting up its first civil registry. The most exciting position I held at that time was supporting the judicial administration team of the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) to integrate minority enclaves into the new judicial system and dismantle parallel courts. In the process, I realized I knew little of the fields I was working in, so I went back to school to do another graduate degree in international and community development. Once I started actual work focused on community development, I fell in love with it and never looked back. It has been more than 18 years now and I feel lucky to have been working in community development, one program after another.

The work of community development specialists spans different areas including, but not limited to, local governance, poverty reduction, conflict management, and emergency support. How do you shift between these different fields?

All those areas mentioned are parts of development. A community development specialist’s role for each of these is significantly different. However, it could also be similar. That would be to help communities achieve development goals efficiently and effectively.

In my work, I handle a wide range of roles depending on the project focus area. How do I shift from one role to another? A lot of the programs that I am engaged in have to do with Community-Driven Development or CDD. The concept is that the community is in the driver’s seat for their own development. They decide the priorities and handle the implementation. The specialists help the community evaluate and select priorities in an inclusive and participatory manner and ensure that the voices of the usually marginalized groups are heard. They ensure that the linkages between government, civil society, donors, and others are made. They ensure that funds materialize for the selected priorities. They help the community implement projects both accountably and transparently to their own communities and the donors.

Some projects are more top-down. There, I am a designer, financial advisor, planner, facilitator, trainer, and even secretariat. In all these roles, the basic premise is that poverty and development are multi-dimensional and need to be viewed holistically. Some projects include multiple, cross-cutting objectives. Others are limited to a single focus area. Once you have done work on some of the broader programs, it becomes easier to also shift between the different roles as needed. Interestingly, larger projects focused on areas such as public infrastructure are much easier to handle than smaller projects focused on areas such as local governance, conflict resolution, and peace-building. You learn the nuances between how to handle them differently over time and, in my case, with many mistakes too.

You mentioned how the work of a community development specialist involves working with states in conflict. What is one of the most pressing issues that you see? Is there any issue that is urgent but is not given as much attention?

Development work is not easy in any context but is especially difficult in fragile and conflict zones. Countries are deemed fragile if governments do not hold full legitimacy and are unable to provide security or social services for its citizens. The most pressing issues in these countries include state or nation-building, local governance and decentralization, human and fiscal capacity, security, public infrastructure, and social service provision and accessibility.

A single development program cannot address all of this. Usually, the international community chooses the development priorities in consultation with the government or civil society. Others incorporate elements to address these issues in every program.

One way that fragile state governments can gain the confidence of its people is to be seen as a basic service provider. If the government is not able to provide basic education or basic health, then that is a vacuum that can then be exploited by the insurgency or anti-government elements. As such, it is especially important in fragile states for the international community to work with the government actors and ensure that the government is recognized as the primary service provider. Health and education services are key markers of government service delivery. Fragile states are also often viewed as highly corrupt. Another challenge of implementing development in such areas is to ensure accountability and transparency in a more contextualized manner. Donor coordination and pooled multi-year funding sources for development activities are essential.

It has been almost twenty years since 9/11 occurred and the Afghan Taliban government was overthrown. Since then, a lot of positive development work has happened in Afghanistan. Afghanistan has moved from the bottom of the United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) ranking to somewhere among the top of the least developed. There has been much improvement in public infrastructure and social services. However, poverty rates have worsened. Does that mean that none of the development initiatives over the past twenty years have been effective? On the contrary, there have been many success stories, but the gaps in security provision have worsened and have undermined many development achievements.

One of your first projects which you supported for over fourteen years was the National Solidarity Program (NSP) in Afghanistan. How did you first start to work in Afghanistan? What were some of the lessons learned?

When I was working for the UNMIK, a former colleague who knew my passion for CDD and who had since moved to Afghanistan approached me with an offer to work for Afghanistan’s Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD), specifically focused on the NSP. I took the opportunity and moved to Kabul in spring 2004. I already had experience in conflict countries, but nothing prepared me for the devastation that I saw in the city. The first step I took was to educate myself on the history, culture, and politics of the country. Then I had a lot more first-hand experience in CDD in the Afghan village context. NSP eventually covered over thirty-five thousand villages and completed over eighty-five thousand subprojects for Afghan villages.

One lesson I learned the hard way is that many development workers try to define milestones to report glowing success to the donors, even when there has been very little progress in the field. There needs to be a push for more honest reporting on challenges and failures without concerns about project shutdown or loss of jobs. Keeping project designs flexible and adaptable based on field lessons is important.

I will give you a couple of stories that might be amusing but make a lot of sense. We were trying to do community grants, and just to show the community how serious we were about women’s inclusion, we said 10 percent of the funds should be devoted to women’s only projects: projects selected and implemented by women. What we were trying to say was that 90 percent of the funds are for the community as a whole, whereas 10 percent of the funds are prioritized for women’s projects, because that is how seriously we take women’s empowerment. Then, on my first field trip, I was listening to my own staff translate this in training to the communities and this is how they conveyed it: 90 percent of the funds are for the men in the community and 10 percent is for the women in the community. As a foreigner, I had not realized until then that biases also exist among our own national and sometimes international teams.

In another instance, I heard staff describe environmental and social safeguard checklists as “balle-balle” forms, which meant that instead of teaching the community on what those safeguards were, they were teaching them which ones to respond with yes or no. A lot of the paperwork and the documentation in the project was to fulfill donor accountability requirements. Project staff and communities quickly learned how to satisfy donors with all the right answers and numbers, but they focused little on the actual quality of the work on the ground. I then learned the need to move to more practical modes of monitoring and reporting.

You mentioned that the project covered thirty-five thousand villages, many of which were outside the government’s control. That is a great number of villages to be covered. What were some of the greatest struggles you encountered in doing so? Were their needs similar and/or different?

Covering the villages was challenging. The thirty-five thousand villages were in more than 90 percent of all rural Afghanistan and in all thirty-four provinces. One of the first lessons I learned the hard way is that there is no such thing as a cookie-cutter approach to handling development in fragile contexts. A lot of us “experts” make that very mistake and assume that a tried and tested best practice from one part of the world, especially if in a conflict environment, can be applied to another country or region. We come in thinking, “I tried this in Ethiopia and it worked great. So I’m going to apply this to Iraq!” It does not work that way. Contextualizing development work to the local context is a must, not a luxury. Development workers need to learn a lot more about the unique country, state, or regional context. This includes familiarizing oneself with ethnicity, politics, power brokers behind the scenes, cultural and religious practices, and gender norms.

Even within Afghanistan, what worked in Bamyan and Daikundi, central provinces populated by the ethnic minority group Hazaras, would not be feasible in Uruzgan or Zabul, southern provinces populated by another ethnic group called the Pashtuns. The need for public infrastructure and social services was intense and the approaches needed to be modified. We needed to trust our field staff, trainers, and facilitating partners (FPs, the NGOs that work with us). We needed to give them levels of flexibility such that every field challenge does not bring the program to a halt or lead to false reporting. So, we jointly drew benchmarks and milestones for the overall program, and then introduced some flexibilities and relaxations in norms, procedures, and processes for working in highly insecure areas.

There are parts of the country that were overrun, managed, or had the known presence of the Taliban, ISIS, or other anti-government actors. There, going with an obvious government-enabled national priority program would be too risky. We needed a project that ensured that the government, not the anti-government actors, would be credited for the work while the project staff were also kept safe. So the project developed what we call a high-risk area implementation strategy (HRAIS). If the HRAIS included flexibilities, these were agreed with the donors in advance. Some core areas were not negotiable since deviating from those norms would mean project withdrawal from that area. But for other processes, exceptions could be made.

You mentioned challenges in women’s inclusion and empowerment in some projects that you mentioned earlier. How were the later projects different? Did they handle this better?

One of the things that I learned is that a lot of the norms and values that I take for granted as an international development worker are not the norms for others. That includes some of our local or national staff who work on these same projects. To give an example, I have met senior Afghan male staff working in various women’s empowerment projects, even in the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, who will never tell you the names of their wives or daughters or send their daughters to college. I had to understand that dichotomy, and while it was difficult to accept, I had to realize that it was the reality I worked with.

A lot has changed in Afghanistan since the Taliban fell. Women are going to universities, women are in government, and there is better women representation in some sectors than in other parts of the world. However, there remains a lot more to be done. Gender concerns and women’s empowerment remains high on the agenda for all donors in Afghanistan. Everyone likes to see gender-disaggregated data and indicators for development efforts in the country. Unfortunately, the reality is that when there is a challenge in funding or implementation (or as currently, with the future of women’s rights given the ongoing “Peace Talks” with the Taliban), the talk is not translated to the walk. Women’s rights remain the last to come and the first to go.

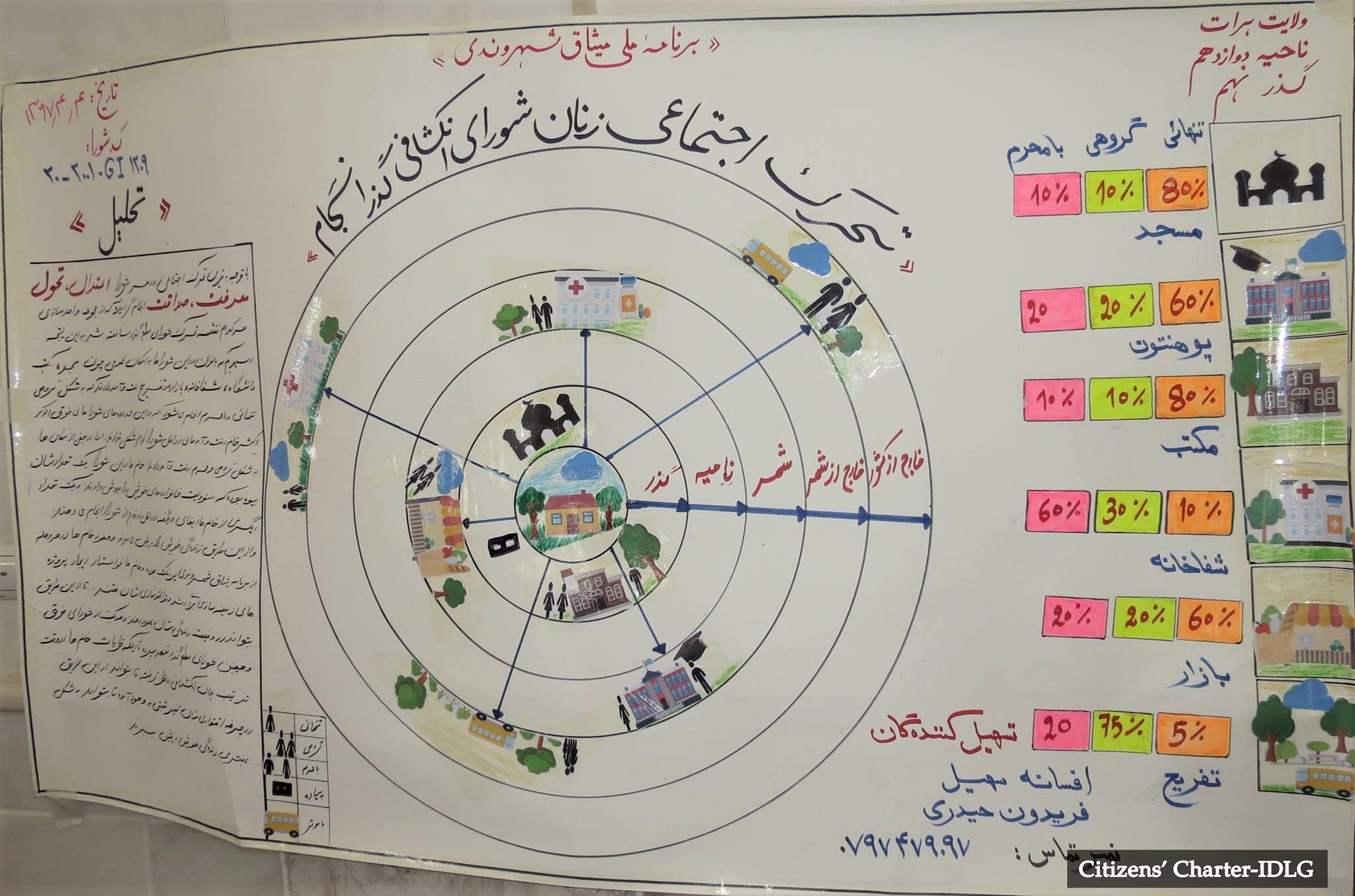

In just about every project that I have worked for, we have set targets for women’s inclusion and participation. While challenging, the targets can still be met one way or another. In many CDD projects in the country, women’s membership in Community Development Councils (CDCs), Gozar Assemblies (GAs), and Cluster CDCs (CCDCs) range from a minimum of 38 percent in very remote rural areas, to over 50 percent in some metro cities, which is incredible when considering the situation under Taliban rule. Input and output level indicators for women are being met, thanks to the quota system, or seat reservations made especially for women membership, staffing recruitment or the like. The less-publicized challenge that remains is whether the high membership numbers actually translated to women’s meaningful participation and voice.

One of the tools we use for pushing the agenda of women’s empowerment is called women’s mobility mapping. We use this exercise of picturing a village in concentric circles from a woman’s home and explore the extent to which she can travel on her own or with a “maharram,” a male relative. Then we gradually reason with them and later with the men in the village on means to improve women’s access to health and educational institutions and marketplaces.

Some measures taken by the current projects include proactive or positive discrimination towards female staff recruitment, special provisions for women staff (including transportation facilities, daycare centers for their children at workplaces), and allowing “maharrams” to accompany women staff on work travel paid by the projects. They also include allowing married couples to be hired together as social organizers such that women can also travel into the villages for work; focused training and capacity building efforts; and maternity leave benefits. We have also worked for strictly enforced anti-harassment policies, sensitizing management on gender-based violence (GBV), and formed special committees set up and trained to handle these cases.

As explained in one of your reports, the NSP monitoring system used the management information system (MIS) which made data used in the project more centralized and accessible. What kinds of data are collected and why is this important? How are stand-alone modules in the database created and used?

As a techno-moron, everything I say in response to this query is as a user, not as someone who understands the complex MIS itself. Both the NSP and its succeeding program, the Citizens’ Charter Afghanistan National Priority Program (CCNPP), have very elaborate databases. I think both are among the most extensive management information systems in the country.

What kinds of data does it capture? Just about every relevant detail from every community that the projects cover. It captures gender, age, employment, and education disaggregated data of elected CDC/CCDC/GA officials, population numbers for communities, and the number of eligible and actual voters. It also captures the population with access to safe drinking water and toilet facilities and the implementation status of the projects. So yes, these are very elaborate MISs.

Both the NSP and the CCNPP also have many subprograms that support the wider objectives of these programs but are also varied enough to have different operational modalities and sub-objectives. Each of these subprograms has a module of its own that links it to the main database.

Given security concerns, it is difficult for donors to access the field in Afghanistan. So most donors currently employ third parties to help monitor the projects. Very elaborate MIS systems such as the one for CCNPP provide donors with accountability since they can access information for even remote communities and subprojects. With a few clicks into the MIS or to the website linked to the MIS, they are provided with a dashboard with real time data of all key indicators in the system.

The other benefit of having these elaborate databases is that they help the project itself learn what has worked. You can gather data and do studies just from the data itself. In one recent example, data showed that costs per kilometer of road varied among many road concreting subprojects in urban cities. This immediately raised concerns, but there were more data that could evaluate why there was such variation in cost for the same output unit. Essentially, these databases not only serve the donors but also help the project address such concerns in-house.

The Citizens’ Charter Afghanistan Project (CCAP), the successor to the NSP, used “citizen scorecards” that Community Development Councils and social organizers completed every six months. Were the scorecards collected for a similar purpose as with the MIS? Could you explain more about the scorecards and what role they played in the project?

The CCAP is the first phase of the ten-year CCNPP I mentioned earlier. One way that the CCAP differed from the NSP was the inclusion of scorecards. The NSP, like the CCAP, provided communities with public infrastructure and social services. To engage citizens further and bring the government closer to its citizens, the CCAP introduced minimum service standards (MSS) that the government promised to provide all citizens covered by the CCAP, in the areas of health, education, and basic public infrastructure. On the other hand, citizens would monitor whether the promised MSS were being met. The charter was an agreement between the government and the people. The government would provide the MSS and the people would monitor and report on them to the government itself.

The scorecards list the agreed service standards in the three areas mentioned. Then the elected CDCs and their sub-committees use them to monitor the provision and standards every six months. So far, anecdotal information shows that there has been at least a 10 percent increase in scorecard performance over the past year, and that the time gap between when a complaint is raised via the scorecard and when it is addressed has been reduced. For example, if teachers were not providing the promised hours of education to students in a particular public school, the scorecard would reflect this and encourage authorities to take action. If action is not satisfactorily taken within the agreed time frame, a complaint can be raised to the district, provincial, and even central levels. In a way, the scorecards are key tools that monitor government service delivery against agreed benchmarks. But it does not seek to replace the data collected for the MIS which are more project specific.

Another project you support facilitated the travel or return of Afghan refugees from Pakistan and Iran back to their home country. What do refugees who return to their home countries most need?

Honestly, I would not know since every returnee family will possibly have unique needs. The reported immediate priorities are usually safer living conditions and employment. The project you mention is called “Esghteghal Zaiee-Karmondena,” which means finding employment in both Dari and Pashto, the two national languages. It tries to create economic opportunities in twelve cities selected for their high numbers of displaced populations.

Currently, with the COVID-19 outbreak and many forced returns, and the onset of the harsh winter months in the country, the immediate needs for Afghan returnees would be food, shelter, and heating. Afghan winter months range from mid-December to mid-March which, with the heavy snowfall in some parts, provide little or no employment in the two biggest sectors: agriculture and construction. As such, it is crucial to support these returnees during these months.

You mentioned that this project involved supporting the economic development of cities with a high influx of returnees. What problems do these cities encounter, in contrast to the refugees themselves?

A basic concept when dealing with migrant and displacement issues is what we call a “Do No Harm” principle. With large influxes of returnees or displaced populations, the strain placed on host communities already struggling with very limited resources, including employment opportunities and public infrastructure, is huge. This then also creates a high possibility of conflict between host communities and returnees. So while the project targets cities with high influxes of displaced populations, its benefits are not only limited to the displaced groups. They also target the whole host communities.

The project can be divided into four main parts: first, facilitation of the return of Afghan refugees to their home country; second, provision of short-term immediate employment opportunities; third, provision of medium to large-scale market-enabling public infrastructure in these cities; and fourth, supporting government to business service regulatory reforms. As you can see, three of the four parts support the whole city.

You are now working with the COVID-19 Relief Efforts for Afghan Communities and Households program (REACH). How has the work been so far? How has REACH been able to help marginalized groups in Afghanistan?

A very difficult question to answer for me, and a sad one, because REACH has been approved as of August 7 and November 9, we have not disbursed a single penny of what was meant to be a quick-disbursing, emergency project. REACH was to cover an estimated five million households–an estimated population of over thirty-five million–with a basic food and hygiene package worth US $50 per household in a single tranche in rural areas, and a similar package worth US $100 per household to be distributed in two tranches in urban areas. Having the first tranche distributed before winter was crucial. However, as we speak, the three implementing agencies are struggling with contradictory instructions from different parts of the government. The parliament is unhappy with the project itself, as they believe it took away funds from other priorities.

So I am sorry to say that so far, the work progress has largely been administrative issues of staff recruitments and procurement of Facilitating Partners. None of the real work needed to fast-track these distributions has yet taken place. We are all still hopeful that things will fall in place soon and we are working towards removing the current bureaucratic hurdles to allow for these relief packages to get to these households before or during the winter months.

Have you found a way to manage the partisan interests in your work?

There is always politics in development. One needs to learn to maneuver around it or to even use it for the projects you work for, where feasible. However, there is again no one approach fits all in this either. Over time, you learn some things that do work. In the context of Afghanistan, it takes staying power and making friends of these powerful politicians until they can trust you and your team to also be working in their interests while protecting the projects’ objectives. Sometimes, all it takes is inviting these politicians to inaugurate projects and giving them media opportunities for the same. Sometimes, it takes repeated and continuous negotiations to ease up on some red tape intentionally created. At other times, unfortunately, it comes to warning project fund withdrawals or return to the donor, and benefits lost to their constituencies being made public.

On a different note, in the World Fellows introductory video by the Jackson Institute, you mentioned a woman named Fatima’s story. Which people or stories you encountered are still memorable to you? Have they influenced your work in any way?

Many people I met through these projects have influenced me in various ways. Some have taught me what not to do, but most have been incredible inspiration. I have learned so much from them that I would not be in community development if it were not for those stories and those people that have moved me. One of the staff that I first worked with was an administrative officer in NSP where I then served as the deputy team leader. He had just returned from years as a refugee in Pakistan. Long story short, he then served as my boss. I moved on to an advisory role in the Ministry, while he served as the NSP’s Director of Operations. His last job in Afghanistan before moving to an international fellowship was as Senior Adviser to H.E. the President of Afghanistan, on migration and displacement issues. He is just one of the very many passionate and committed young people I have met who want to make a difference for the better.

Another story immediately comes to mind. Every couple of years or so, we hold national conferences where we bring together CDC representatives from more than four hundred districts in the country to meet with the country leadership. A day of prepping starts off the usually three-day program. During the first day, the participants hold working groups to respond to several important queries on issues that matter to them. Over the next two days, they present their findings to the country leaders. In one such gathering, the male CDC speaker had just finished speaking and the woman CDC member had just taken the podium, when the president of the country, seated immediately in front of the podium, was called away for something obviously very important. He was about to leave the building when she took the microphone and demanded, “Mr. President, are you only the president for the men in the conference here, or are you also the president for the women in the country? If you are the president for the women in the country, you need to stay and listen to me too!” It was an incredible moment. No one could have predicted or prepared for it, but it was true women’s empowerment on display. To his credit, the President stayed and listened to her. Watching that spontaneous moment made my whole life’s work worthwhile.

What led you to Yale? How has the World Fellows Program been? What are your plans after leaving Yale?

The past twenty years of my life, except for a brief maternity-related break, has been work, work, and work. When you work in these environments, your life gets consumed with one emergency after another and one conflict after another. I was and still am a workaholic and I used that as an excuse to not even attempt a PhD, something I had intended to complete before I was 35. Then last year, a friend of mine told me he was going to apply for the Yale World Fellows 2020 program and asked me to review it for him. When I did, I found the reviews from alumni very positive, and began considering applying myself. I did think I was much older than the actual average age they were looking for, which was 35, and so suited my friend better. But he then coaxed me into applying too. It was the first fellowship I had ever applied to and I did not expect to succeed, but I was shortlisted, interviewed, and selected. After I got confirmation of selection, I learned more about the program itself and became much more excited about being a Yale World Fellow (YWF).

How has the program been? It has been wonderful in many ways, but meeting and becoming friends with my cohort here has been the best part. The other thirteen Fellows for 2020 are such a diverse group, ranging from wildlife conservation to human rights activism, from grassroots peace and healing movements to heading the CNN bureau for Africa. I can honestly say I have learned so much from them all. I have also learned a lot from our guest speakers including General Patreaus, Staffin de Mistura, and Stathis Kalyvas. They are such stalwarts in their individual areas. In my line of work, I may have gotten to meet some of them over a span of two decades, but here, I met these world leaders and experts in only three months. Unfortunately, because of the pandemic, we did miss out on a lot of what would have been amazing parts of the Fellowship, such as being on campus, attending classes, doing events in person, or interacting with students, faculty, and program speakers.

I also realized that there is so much work that I do that is not being documented that could help others who are working in international development or students interested in global affairs, if I could only document it. I have been talking to a couple of Yale professors about starting a series of video lectures, writing papers together, or sharing my work with them so they can put it in writing. This might help me use the extended lockdown period to be productive, while giving back to the development world from my work experience in fragile and conflict states.

What advice would you give to Yale undergraduates interested in development work?

I think there are two groups of people who want to go into global affairs and development work. There are ones who have the mission of making the world a better place and to change things for the better. They see polarization, inequality, and poverty. They often come from a position of privilege and they want to give back. Or, like me, they might come from a “third world country” and want to change that. There is a lot of idealism involved with that group. There is another group–and I am sorry to say that they are also very present, because I do encounter those young people as well–for whom going to Afghanistan, Syria, or Iraq is just a great thing on their CV, a step up to working with USAID, DFID, or the UN.

My advice is limited to the first group–the ones who really want to make a difference. To them, I would just say two things. Do not lose that idealism. Keep that idealism and those values. You are especially equipped to make good change in the world. You come from one of the best institutions in the world. You get one of the best worldviews studying here and meeting diverse people. But before you go into the field for work, learn a lot more. I had been so naïve when I first started working in this field. I saw things in black and white. I believed that the UN was this one institution that was the best at everything. But once you are there inside the system, you see that any organization or institution is only as good as the people it has. Even these organizations formed from high ideals have collusion, discrimination, corruption, and harassment. There are many who are in them purely for the title and the money.

So, go with the idealism, but also equip yourself to see better and do more. Do not ever go into fieldwork without learning a lot more about the country that you are going to. See if you can face those realities. Do not go with textbook theories in your head and feel that you know everything. Speak to the locals and be willing to learn from everything you see on the ground. You will realize that the most illiterate villager can teach ten times more about what his village needs than any textbook can teach you. Never, ever equate illiteracy to stupidity. Some of those illiterate people are the smartest and wisest people I have met. At 46, I am still learning every day!

Sophia Kang is a first year in Timothy Dwight College. You can contact her at sophia.kang@yale.edu.