A Pierson Tea with Hamza Yusuf

By Rosa Shapiro-Thompson

[divider]

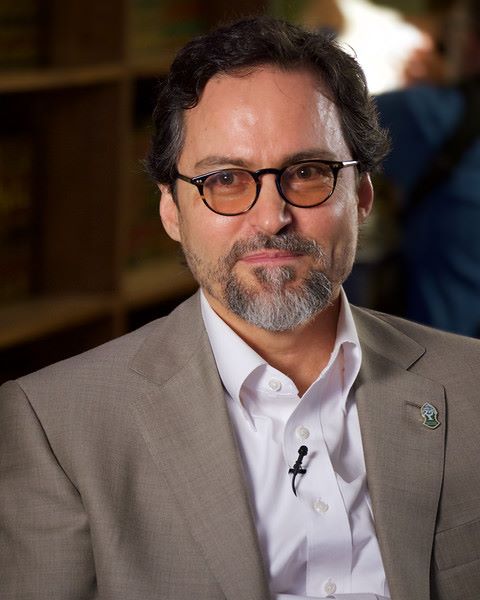

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n April 7th, Professor Stephen Davis, Pierson’s Head of College and a scholar of early Christianity in Egypt, welcomed Sheikh Hamza Yusuf to campus. According to Egypt Today, Sheikh Yusuf is the “Elvis Presley of American Muslims.” As the founder of Zaytuna, the first American Muslim college, he is indeed a rock star of Islamic theology in a country that is too often hostile towards his religion. Jokingly, Professor Davis cited Egypt Today and introduced Yusuf as an American Muslim Elvis. This set the stage for a funny, insightful, and heartfelt conversation.

The Pierson College Tea (formerly “Master’s Tea”) drew a large crowd of Piersonites and other Yalies. Although the advertised title of the talk was “Understanding the Origins of ISIS, Political Islam, and the Arab Spring,” Yusuf only briefly touched upon this topic. When pressed on the subject, he emphatically argued that ISIS—a violent group that itself traumatizes many Muslim—does not follow Islam but contravenes its teachings. The Prophet Muhammad commanded his followers to feed orphans and prisoners, but ISIS abuses its prisoners. ISIS destroys thousand-year-old churches in Iraq—but, Yusuf argued, if it were truly Muslim to destroy churches, how have Iraqi churches and mosques coexisted for millennia? The ideology of ISIS, then, deviates radically from the broadly accepted theology of Islam. In Yusuf’s view, arguments that ISIS is Islamic, or even “very Islamic” (see Yale Political Science Professor Graeme Wood’s recent piece in The Atlantic) are theologically erroneous and dangerous.

“Benjamin Franklin understood Islam better than ISIS,” quipped Yusuf. “I’m not even being facetious.” The mood lightened.

Despite some discussion of political Islam, the majority of the talk focused on Yusuf’s own experiences. Yusuf described his experience as an Orthodox Christian converting to Islam and the unique perspective he has built through his experiences. As a convert to Islam, Yusuf believes that he can see the distinction between religion and culture more clearly than other Muslims. By way of example, Yusuf touched upon differences in dress codes: while Muslim women in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia express their modesty in black abayas, those in West Africa express the same modesty in bright fabrics. Islam is not its culture but its moral principles.

Yusuf moved on to a discussion of his belief in morality-as-verb. “We are to be judged by our actions,” he told the audience, citing a passage of the Qur’an. We cannot judge another’s intent. Drawing on his views on morality, Yusuf moved from the theological to the political. He began to comment on historical trauma and past injustice. He urged the audience to remember that while we inherit the effects of past sins, we do not inherit the guilt of the sins themselves. “The Jew born today is not the Jew who invaded Palestine,” he said, just as we, living on stolen native land, did not commit the theft and genocide of our state’s formation. We must recognize the past, but more importantly we must act morally in the present.

Yusuf next urged the audience to empathize with the trauma of others. As he recalled the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the devastation beyond belief, and the friends he lost, Yusuf was moved to tears and brought audience members along with him. “I believe that all war is terrorism,” he said. “It traumatizes people.” The room was silent, saddened.

The audience appeared moved by Yusuf’s arguments. Andrew Moran (BR ’19), a student in attendance who studied Arabic in Morocco during his gap year, commented that he found Yusuf’s focus on forgiveness particularly powerful. One student, Ahmed Elbenni (TD ’19), who is active in the Yale Muslim Students Association (MSA), considered Yusuf extremely insightful. Elbenni agreed with Yusuf’s commentary on ISIS, calling the argument that ISIS is Islamic “shallow and easily debunked.” Elbenni also said that he “particularly appreciated Yusuf’s remark that people, Muslims or otherwise, conflate culture with religion.” Elbenni commented on his own experience as an American Muslim, explaining, “This resonates with me as I have observed it many times in my own local Muslim community back at home.”

When Yusuf invited questions, a woman asked if he could give examples of beautiful things from Islam that she could “sing from the rooftops” to counter the increasing Islamophobic vitriol in American political culture. From Islamic civilization comes great food, Yusuf noted. The word sugar comes from Arabic, so does sofa. “You’re all sitting on sofas, and there’s a reason an Ottoman is called an Ottoman.” And theologically, Islam is the only religion never to have promoted doctrines of racial inequality, but rather upholds racial equality as a core principle.

Much good comes from Islam’s principles and people, Yusuf stressed. Islam is not monolithic, nor is it ISIS. Sing it from the rooftops.

[hr]

Rosa Shapiro-Thompson is a freshman in Pierson College. Contact her at rosa.shapiro-thompson@yale.edu.