Defining the Privileged Refugee: Humanism of Humanitarian Status Quo Preservation After the Russian Full-Scale Invasion

by Nataliia Shuliakova

Unfinished tea.

A phone left on charging next to it.

A vase of dried flowers on the coffee table.

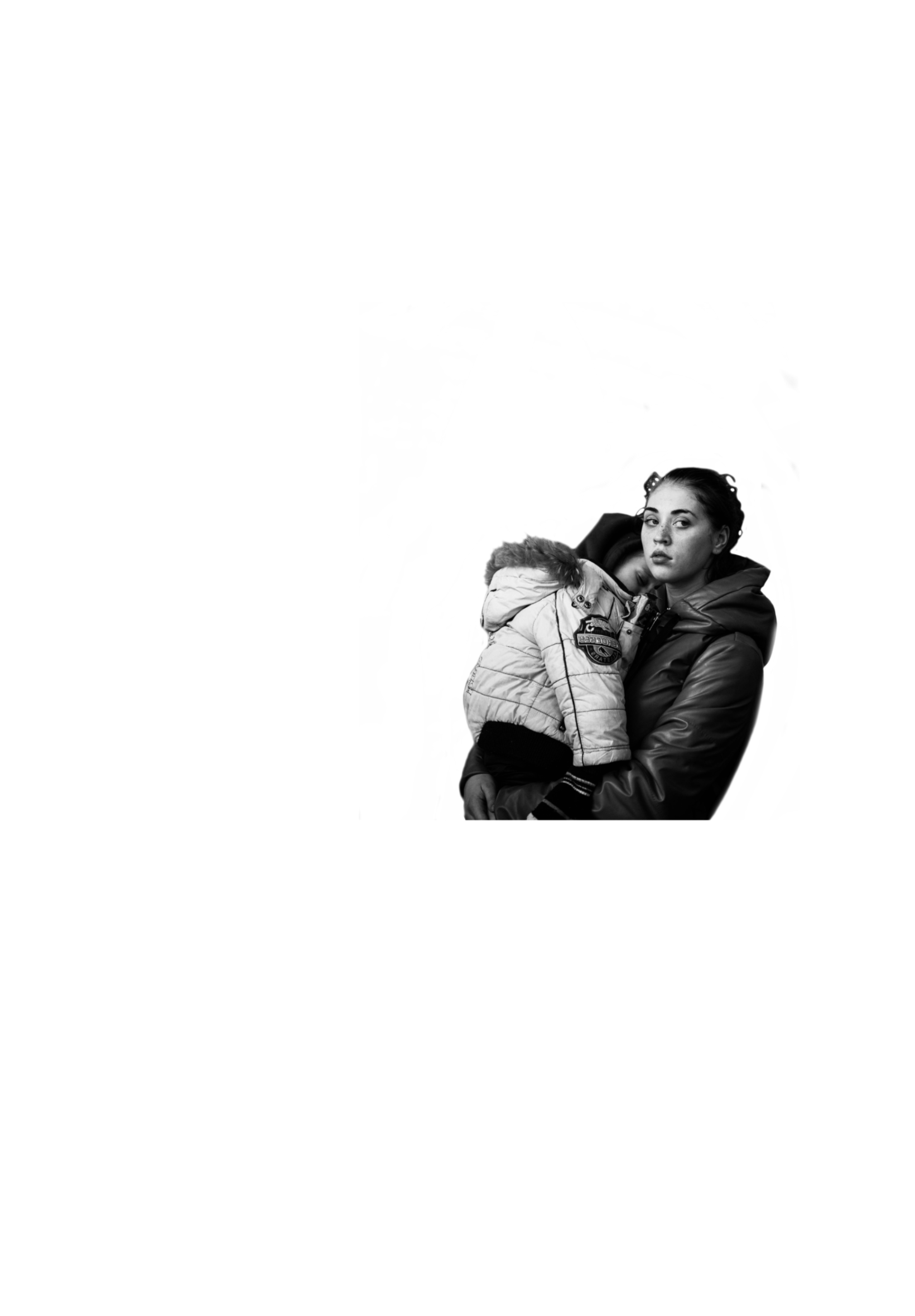

On the morning of February 25th, everything dear to heart was already packed in the backpack and, the following week – loaded in the car’s trunk. Shortly after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022, the streets of major Ukrainian cities were flooded with people who packed up their lives and fled in the hope of returning home to their unfinished tea soon.

The unprecedented attack on a sovereign country within Europe’s borders provoked miles of cars at the crossborder checkpoints of neighboring countries and, not long after – responses from the international community. The threat of a large wave of Ukrainian refugees was at the center of the international community’s discussions in the event of a Russian invasion. Experts have been discussing the possible outcomes of supporting Ukraine after Russia kept pressuring the USA and its European allies by mobilizing thousands of troops near the Ukrainian border in February 2022.

The global community appeared to be mobilizing its resources in preparation for the forthcoming extraordinary events. However, nobody predicted the actual scope of the refugee crisis, which ultimately unfolded as the biggest European population displacement since the end of the Second World War. In this light, the EU and numerous other countries showed their highest level of support by implementing swift and effective admission policies, which had not been present ever since the start of the conflict in 2014.

Writing this from a position that may seem privileged to many, I feel responsible for reflecting on the given privileges. I am a student at Yale University in the USA, and I became a foreign student in Europe shortly after the start of the invasion. While I did have to stay 8 hours on the Romanian border before being granted permission to cross it, along with millions of other Ukrainians in the line, I was eventually allowed to cross the EU border to escape the horrors of war.

When considering how the accounts of the warm reception of Ukrainian refugees might have appeared to displaced people from other countries, one is tempted to call the position of the former privileged. Even if you are an underage third-country national escaping a war with your family, lacking a secure legal or economic standing, it remains crucial to recognize that many did not possess even these modest advantages. Even though those “privileges” do not fit into the sociological definition of privilege, they were important advantages that were accessible to one group and not to another.

It is essential, however, to differentiate between my own reflections on the complicated meaning of privilege and the actual circumstances on the ground. Over time, the initially “welcoming” reception of Ukrainian people has revealed its true nature. With the exception of a few countries like Germany, where conditions are comparatively more favorable, many individuals have found themselves largely self-reliant, receiving limited or inadequate support from EU member states.

While statistics may provide insights into the pressing needs for accommodation and employment, they fail to capture the hurdles and cyclical challenges people encounter while attempting to access these rights. Moreover, they do not fully depict the actual living conditions. It is not uncommon for people struggling to make ends meet to choose to return to Ukraine despite the ongoing safety concerns. Additionally, research on the reception of displaced individuals from Ukraine indicates that in the long run, being placed in the relatively new and underdeveloped framework of temporary protection (along with its various implementation models at the national level) may give rise to several vulnerabilities when compared to other forms of international security, such as refugee status and subsidiary protection.

When waiting for one’s turn at the Polish, Hungarian, Moldovan and other closest bordering countries’ checkpoints, every family found themselves constantly refreshing the page of the State Migration Services website. In addition to contemplating the safest places to stay, especially for those with children, people seeking temporary asylum had the added challenge of ensuring they did not infringe upon the rights of border crossing, which for the first months after the invasion were unclear even to the European Commission itself. In my family of three, I assumed the responsibility of understanding the rules outlined in Paragraph 24, drawing only on my two years of German language classes in high school.

Some people crossed the borders to the nearest countries without much time for consideration, only to realise later that obtaining a residence permit, let alone refugee status, was a daunting challenge in certain countries. While not impossible, the process felt like an enduring struggle with a bureaucratic system, sometimes in plural. The establishment of new norms and regulations persisted even a year after the invasion when the initial efforts to welcome new asylum seekers were taken. Most Ukrainian asylum seekers leaned towards neighboring countries for temporary residence, particularly Poland, Hungary (although with additional complications), Slovakia, and Moldova. Many already had friends or family residing in these countries before the outbreak of the war, providing immediate contacts for navigating urgent safety-related questions. However, a significant number of forcibly displaced Ukrainians faced the pressed decision of leaving some family members behind due to various reasons, such as husbands unable to cross the border due to martial law, elderly parents, or those unwilling or unable to relocate.

Even months after the admission of new regimes of identities-borders-orders (Steven Vertovec, 2011), there were precedents when the host country’s inability to establish and clearly convey its policing measures directly harmed the displaced peoples’ safety. For example, in the summer of 2023, there were numerous instances where Ukrainian nationals, due to the ambiguous terms of Polish-Ukrainian border-crossing laws, lost their temporary protection status after brief visits to relatives in Ukraine. The subsequent procedures to regain these statuses took considerable time to establish. Faced with the distressing and unclear nature of these processes, many individuals opted to remain in war-torn Ukraine rather than undergo the challenges of reclaiming their protection status.

On March 4, the Council of the European Union activated the Temporary Protection Directive, which entails the granting of temporary protection status to individuals from Ukraine. This status differs from refugee status and is intended to afford them rights to access the labor market, education, and healthcare (although, as noted, the actual realization of these rights presents its own set of challenges). However, at least two arguments suggest that this solution ultimately upholds and perpetuates the current status quo and the existing EU border regime.

Firstly, despite the extension of protection status for individuals from Ukraine until March 2024 in response to a full-scale military invasion by Russia, there is an agreement that this protection is temporary and can be revoked almost at any moment, not necessarily contingent on conditions being appropriate for return (Mencütek 2022). Eurostat indicates that 4.1 million Ukrainians are registered for temporary protection in EU countries. The EU Council website further notes that individuals fleeing the war from Ukraine will continue to receive temporary protection until March 4, 2025.

Secondly, processing displaced people from Ukraine through a distinct status and procedural track enabled the EU asylum regime to remain unaffected by the sudden surge in the influx of people. This proactively averted the need for adjustments, let alone significant changes, that might otherwise have been required, leaving the European border regime unchanged.

As of September 27, 2022, the European Commission of Migration and Home Affairs documented 7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), including 3 million children. There were also 11 million entries into the EU from Ukraine and Moldova, with 9.6 million entries attributed to Ukrainian nationals. However, only 4.3 million individuals registered for Temporary Protection in the EU, and a mere 26,200 submitted asylum applications, as reported by the European Commission in 2022.

These numbers reflect the count of formally registered externally or internally displaced people and underscore the notable division between de facto and de jure displaced persons. It adds another layer to the discussion on the complex nature of contemporary displacement from Ukraine and the so-called privileged position, which, in certain perspectives, is rightfully acknowledged among the refugee population. But, as demonstrated above, this position carries terms that are incompatible in nature.

This raises a critical question about accountability. Recognizing that Ukrainians might have more favorable conditions compared to some other at-risk groups seeking asylum globally is one thing. However, placing the responsibility for these disparities on the asylum seekers themselves is misplaced. In reality, the accountability should rest with the system that has perpetuated and continues to permit such inequitable treatment of various refugee groups. However, it is unreasonable to expect the Ukrainian displaced people to rectify the problem themselves. Instead, the responsibility should be placed on European immigration policies enforced by nation-states and coordinated by the European Commission, which initially caused these rifts.

Thus, the perceived relative advantages extended to individuals from Ukraine through their temporary protection status, including certain rights and the opportunity for mobility within Europe, can be characterized, borrowing from Paulo Freire’s terminology, as a form of “false generosity” (Freire 1970). This “false generosity” allows the EU to uphold its current border regime and perpetuate the injustices it imposes on displaced people of other nationalities. This form of generosity is not genuinely humanistic but rather humanitarian (Freire 1970), as it simultaneously serves to sustain the current EU border regime relatively unaltered and the overall state of affairs in its convenient status quo.

Nataliia Shuliakova is a first year in Trumbull College and can be reached at nataliia.shuliakova@yale.edu