Catfished by Carbon Credits and Nuns: Exploring the Implications of International Misinformation on Forest Carbon Sequestration Potential

by Camila Young

Last summer, I attempted to live the life of a nun. Just for a month. After finding a job posting for a gardener position at a convent in Sardinia, I was enthralled. They promised a place to sleep in a church dating back to between 1065 and 1082. While I personally have never considered entering into an order, I thought it would be fascinating to be cloistered for a few weeks in a building breathing history. All the while, I’d be able to assist in the upkeep of their olive groves. When I landed in Sardinia, I was greeted by a grinning Argentinian volunteer, who ushered me inside and gave me the keys to the front gate.

The grounds were overrun with cats, and religious statues dotted the halls. The convent was structured around an internal garden, with a statue of—presumably the Virgin Mary—at the center. Citrus trees enveloped her, and flower bushes crowded the ground. Looking at the facade of the building, its old age was unmistakable. The paint was peeling, the stone crumbling in some places, and there were most certainly bats in the hallways. Nonetheless, it emanated charm.

That charm made up for the absence of clean running water, enlisting a walk to the well every morning.

That charm made up for the lack of air conditioning, prompting reliance on the cool breezes

That charm made up for my inability to communicate until I learned some Italian (however, I got by, for the most part, with Spanish)

That charm didn’t make up for the lack of nuns.

What kind of convent doesn’t have nuns? You can imagine my disappointment. Instead of the building being taken care of by an order, it was simply a team of nomadic volunteers and locals in charge of the church’s upkeep. It was quite a vibrant group of people, from the aspiring nudist to the spiritual counselor who practiced stick-and-poke tattooing as a form of healing. As for nationalities, there was Italian, Argentinian, New Zealand, German, Spanish, Egyptian, and American representation.

Considering we were living in a heat wave, the prospect of climate change crept into the conversation. Reflecting on it now, it was quite naive of me to think that climate change was a universally accepted fact. It most certainly is not. Although I don’t speak very much Italian, five Sard men laughing at you and calling you ‘pazza’ leaves quite an impression.

On the other hand, the Argentinian volunteers I spoke with agreed wholeheartedly that climate change was real, proceeding to provide personal anecdotes about their mountain’s glaciers melting and the dwindling fresh water supply in their home country. The Spaniards’ ambivalent response implied that climate change was irrelevant to their lives. An American-turned-Italian went as far as to claim that climate change cannot possibly be happening since there are so many trees doing photosynthesis, and it’s obviously science that they take in carbon dioxide.

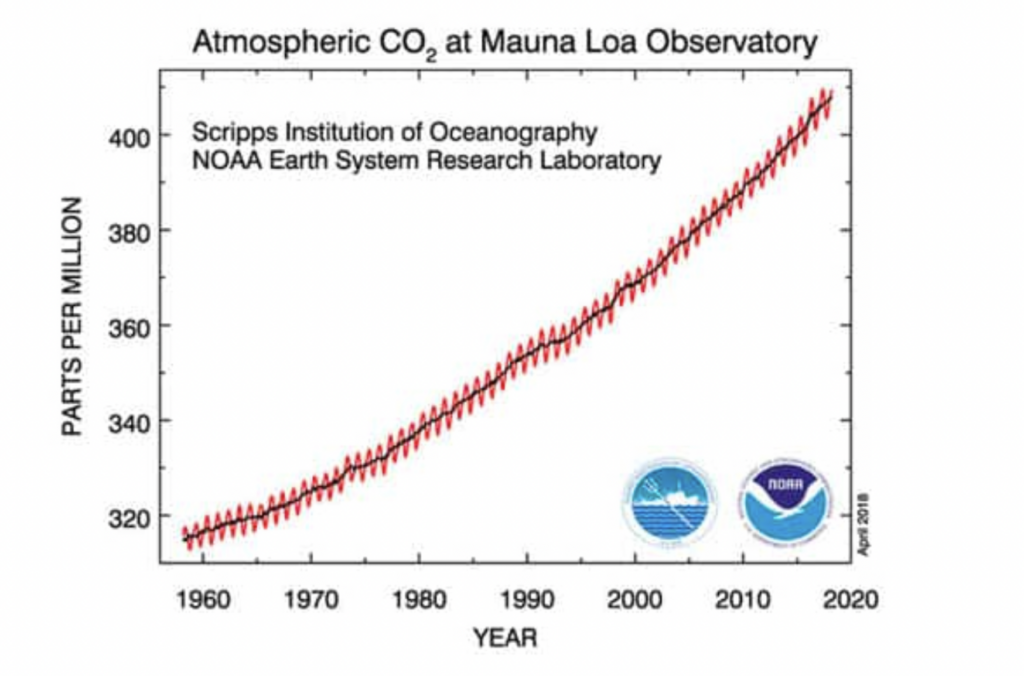

This experience should not be taken as a generalization about how an entire culture views climate change. On the other hand, the convent serves as a sampling of a few climate misconceptions circulating internationally. The most astonishing was an utter refusal of climate change’s reality. However, arguing with complete denial I found to be quite unproductive. I could show them the Keeling Curve (a record of the drastically increasing atmospheric CO2 from 1958 to the present day), introduce the science behind the heat-capturing ability of greenhouse gases, or explain our exorbitant release of carbon dioxide as a result of industrialization. However, it still would be threadbare and unmoving for some groups.

A year ago, I had a conversation with the co-founder of Weather Underground who explained how in the United States there are six climate thought bubbles, or “6 Americas.” An individual can be alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful, or dismissive when it comes to their climate change sentiment. The distribution of these six audiences has changed drastically throughout the years. There has been a recent uptick in ‘alarmed,’ meaning the American public has become increasingly aware of the immediate threat of climate change and supports the implementation of climate-based policy. However, the studies he referenced approach the issue solely within United States borders. On the scale of the international volunteers at the convent, I found there to be four pools of thought: traditional, unbothered, misinformed, and accepting.

The Traditional

These are the individuals who find comfort in what they know and have been told in the past. Unless the climate becomes of direct relevance to them, it is in the periphery and therefore insignificant. They deny climate change because it would mean a divergence from their preferred life mindset. A ‘live in the moment’ mindset, for example, can foster this sentiment if it is practiced without regard to coming generations. Alternatively, someone who is reminiscent of preserving tradition and generational knowledge would fall into this category.

The Unbothered

These are the individuals who may know climate change is happening, and may accept its consequences, yet do not recognize the need for urgency. The volunteers who fell into this category tended to be younger (18–30 years old). It seemed like the dissonance of too many climate opinions made these people just lose interest in having an opinion.

The Misinformed

These are the individuals who rely on fragmented science to assert a point of view that climate change will fix itself ‘naturally.’ Similarly, it could be the ones who claim climate change as a whole is natural. Particularly, there was an overwhelming sentiment that trees would save us by taking in all excess carbon.

The Accepting

These are the individuals who believe climate change is happening and that we need to do our part to help. These tended to be the ones who experienced such stark climate changes within their daily lives that they were forced to believe in climate change.

Addressing Misinformation

Out of all these mindsets, I found the most destructive to be the ‘misinformed’ because they tended to be the most outspoken and had the greatest potential to lead other individuals to believe climate change is insignificant. This is where the Italian-American volunteer fell, and he was able to turn many of the unbothered younger people to become blatantly climate-opposed. His greatest defense lies in the ability of trees to hold carbon.

While it is true that through photosynthetic processes trees take in carbon dioxide and store it in their biomass, and this process does exceptionally well to help reduce the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, we should not rely on forestry to save us. Interestingly, it is the oceans that absorb the most carbon dioxide comparatively. Nonetheless, we are expelling carbon dioxide at such a high rate and quantity that an unnatural amount of it will stay in the atmosphere. This is not to say trees do not help, in fact, there has been an industry propped up around using forests to curb our atmospheric carbon. In order to better explore the validity of this volunteer’s claim that forests will save us, I spoke with Ph.D. student Reid Lewis at Yale’s School of the Environment. Lewis studies forest carbon dynamics and has experience assessing forests for their carbon-offsetting potential, and he helped me explore the possibilities and drawbacks of these carbon-based markets.

Lewis’s not-so-hot takes

“There are portions of forest carbon finance which are very exciting, particularly jurisdictional-scale crediting in REDD+ nations…but [this excitement is not held with] project scale forest credits, particularly in the US.”

While Lewis entered the field hopeful that forest carbon credits could be a great way to confront climate change, he became increasingly skeptical as he looked into projects that supposedly generated lots of offset credits. He noticed many projects “exploited” the protocols in place that led to offset creation, overpromising the actual carbon impact they could provide. He conceited a lot of complexity with the topic of quantifying the carbon sequestration potential of a certain forest. However, in general, he sees support for the resonating backlash against many of the forest carbon offset credits made in the past.

Lewis broke down the two different scales of carbon credits and gave his opinion:

1. There is a country-wide or jurisdictional scale where financing would go directly to the governments and Indigenous communities who control that land. This would involve measuring deforestation reduction across very large areas, like states or countries. The benefits of this model lie in financing more established governments and communities with greater power to do something comprehensive, and these models likely provide a more accurate estimation of true carbon sequestration. With large swaths of land, the abnormalities in certain pockets of trees would be better accounted for, and you better capture timber harvests spilling over into a neighboring forest (a process we call leakage).

“You are directing finance to the people who can do a lot about deforestation.” -Lewis

2. There is also the project-level scale, where a given property is paid carbon credits to be preserved. Rather than thinking about the country as a whole, you look at a particular property and think: what would happen to this particular strip of land if you did not finance it with forest carbon credits? This is the model taken on in the United States, and Lewis expressed a greater hesitation with this scale of carbon crediting. His hesitations mostly lie in the realm of additionality described above: there is a greater chance of “creative accounting” of the smaller spaces where actors can more easily “game the system.”

Here is a thought experiment to consider: if a company owns a swath of land and says “I will slash and burn all of this if I do not receive carbon credit funding,” the credits they sell are based on the counterfactual gain from not cutting that forest. This business model is largely built on theoretical gains, instead of a tangible, sellable commodity. The company would be incentivized to account for the ‘forest saved’ in the most exhaustive and carbon-heavy way they can get away with. The key question is about additionality: would they have actually slashed and burned their forest? He admits ‘additionality’ is “incredibly hard to [asses], to the realm of impossible” in these situations. Lewis described an instance where he saw a company grossly exaggerate how much of the forest they would have cut without the carbon credit funding.

Given we do begin the implementation of jurisdictional level carbon credit schemes, Lewis thinks we should choose equatorial regions. Each unit lost of the highly productive equatorial forests would mean massive losses in biodiversity, making them prime to be conserved. And when we do support these projects, we should strive to uphold REDD+ goals – providing financial support to developing nations so they can be empowered to develop as they choose without losing their incredible forests.

The Bigger Carbon Context

While there are certainly ‘correct’ ways to go about forest solutions to climate change, much of the current system is based upon commodifying forests. Essentially, people are trying to profit from trees just being there, doing things they would have done otherwise. Rather than preserving a forest for the sake of its intrinsic, more nuanced and wholistic value, we try to quantify its importance through our carbon standards. It seems like an environmental cash grab.

On the logistical level, we are trying to retrace our steps when we shouldn’t have been walking forward in the first place. Why try to press the ‘undo’ on our carbon dioxide release after the fact, when we could be halting the process outright? To see legitimate progress in our climate goals outlined in the Paris Agreement, we must divert the way we industrialize so that production releases minimal carbon dioxide. As for the energy sector, switching to renewables which don’t release greenhouse gases is optimal.

Why haven’t we seen this happen? Money.

Although this is a much more effective solution, it would require an overhaul of the way many industries operate. Of course, large-scale change is not in the vocabulary of a company operating on great profit margins. The transition to renewables would concern major upfront investments and years-delayed benefits. Not to mention, companies are still milking returns of previous investments in ‘brown’ energy. These major transitions most likely won’t take place until it is financially favorable for them to.

However, this is operating under the assumption that we continue business as usual. There are political maneuvers that could spurn this change, such as a carbon pricing scheme along with a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Measures like these have already been implemented in the EU. Working on such solutions in more inclusive frameworks like within the World Trade Organization (WTO) has great potential. In fact, after interviewing a secretariat of the WTO this summer, I was told that there is potential for environmental carbon pricing on the international level given proper attention is allocated to it and compromises are made. However, this would require a substantial investment and proper aid to countries that do not have the means to achieve the climate transitions themselves.

While the Italian-American volunteer’s idea that trees will be the ultimate savior of all climate change has some truth, relying on tree-based carbon offsetting is a flawed system in many instances. Hope has its place when confronted with the prospects of rising temperatures, but that hope shouldn’t serve as rosy glasses. Just like naivety will be met with bitter truth in any other upcoming industry, the green industry has the potential to be exploitative. Treading with vigilance is necessary in these new markets. At the same time, many genuine efforts are in progress, and this is no time to fall to complete nihilism.

I may have been catfished by the potential existence of nuns, but the same doesn’t need to happen with carbon credits. As the climate pendulum is swinging towards more bitter ends, we are tasked with halting its momentum with valid means.

Author’s Note: Any forest allocation to carbon credit schemes should account for the indigenous communities that may have previously safeguarded those areas. The negotiations involving the land of indigenous peoples should be made with these communities involved.

Camila Young is a sophomore in Ezra Stiles College and can be reached at camila.young@yale.edu.