Exceptionally Promising Students: A Look At Education Programs In Prisons

Featured image: Students learning during a class offered by YPEI at the MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institute in Suffield, CT (Source: Bard Prison Institute)

By Sarah McKinnis

Read the pdf of the article here

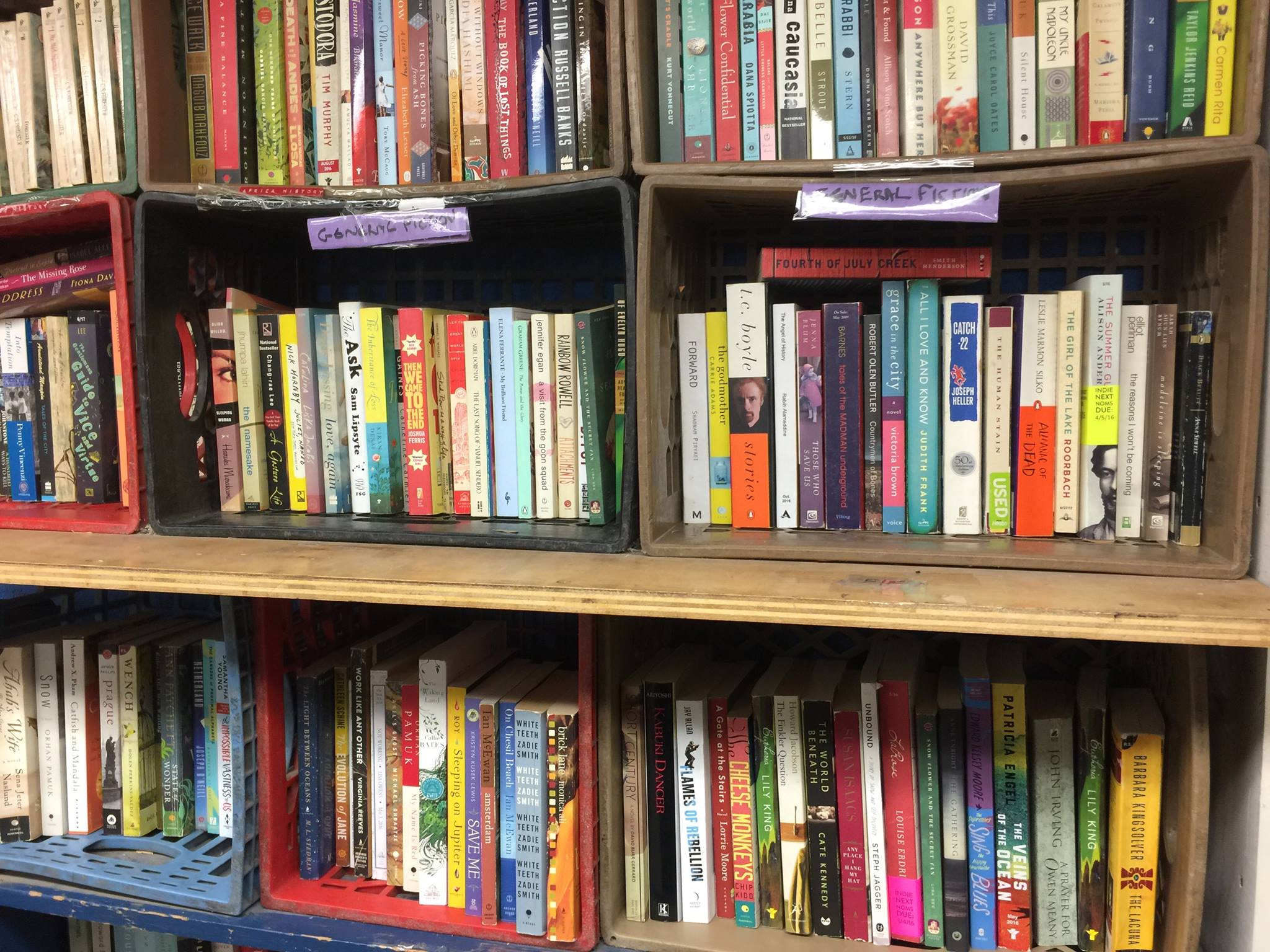

The whiteboard at the back of the room details the class schedule for the week, which includes an Ethnicity, Race & Migration course and a Physics course. Previous offerings included English classes such as “Readings in American Literature,” a Philosophy course, and an introductory Latin course taught five days a week over the summer. These are rigorous Yale classes taught by esteemed professors to a select group of engaged learners. However, this was not taking place in a lecture hall in New Haven, but instead in Suffield, Connecticut, where the Yale Prison Education Initiative offers courses at the MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institute.

Founded and directed by Zelda Roland (BR ‘08 & PhD ‘16), the Yale Prison Education Initiative (YPEI) offered its first courses in the summer of 2018 through Yale Summer Session, marking the first time an incarcerated student was enrolled in Yale College. YPEI also offers not-for-credit courses five days a week during the fall and spring semesters; Roland hopes to offer B.A. courses for credit soon. Enrolled students go through a competitive admissions process and they are connected with Yale resources such as graduate and undergraduate peer tutors and editors. Roland explains, “Every time we put up flyers [advertising the courses] we get 600 applicants.” They only admit ten to twelve students, making YPEI statistically more selective than Yale College itself.

Similar programs aiming to bring higher education opportunities to incarcerated individuals exist at other universities—including nearby at Bard, Wesleyan, Cornell, and Princeton—and are changing the lives of their students by acknowledging their dignity and giving them an opportunity to exert more control over their lives, something often denied to people in prison. One student at MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institute writes in a testimonial posted on YPEI’s website that “For the first time in 12 years I have had a real positive change in the quality of my day to day life. Thank you so much for being the spark of that change, I have it because of you and it makes me work harder knowing that it’s a responsibility not a gift.” The drive and passion exhibited by these students were also evident when I spoke with Jenny Greene—the Co-Founder and Academic Director—and Jill Stockwell—the Program Director—at the Prison Teaching Initiative (PTI) at Princeton, which currently offers courses to fulfill an Associate’s degree and a small number of courses that count towards a four-year Bachelor’s degree. “They’re just the most engaged learners I’ve ever worked with… It’s a wonderful environment to teach in,” Greene told the Globalist.

From my conversations with those involved in both PTI and YPEI, support from other educators and faculty has been just as positive. Roland described widespread support throughout different departments at Yale, among both faculty and students. This semester, Paul Tipton—the former Physics Department chair—is teaching a course, and Professors Roderick Ferguson, Daniel HoSang, Lisa Lowe, and Leah Mirakhor are co-teaching a seminar through the Ethnicity, Race, & Migration department. Two graduate students are implementing a Latin curriculum, another is serving as a Teaching Fellow for Professor Tipton’s course, and one is serving as a Graduate Professional Development Fellow. Undergraduates also volunteer in prison as peer tutors and on-campus as research partners. Similarly, at Princeton, there’s strong support from the faculty, with about 100 volunteers—professors, graduate students, and postdocs—teaching each semester. PTI is “one of the largest volunteer opportunities for graduate students,” Greene tells me. Stockwell herself got involved with the program initially by teaching literature classes as a graduate student.

Despite the success of these initiatives and the incredible faculty support, YPEI finds itself clashing with administration on several levels. Yale is currently deliberating if YPEI can offer classes for credit year-round, and there are political challenges inherent in the organization’s work. There has long been a sentiment in some areas of government and specifically from those with a more conservative political ideology that incarcerated individuals do not deserve an education, and that resources are better spent on people who are not in prison. This outlook is not uncommon—as former New York State Senator George Mziarz has been quoted saying, “‘Do the crime, do the time,’ not ‘do the crime, earn a degree.’” As such, support for these programs can fluctuate based on which local and state government officials are in charge.

Nonetheless, these women and their programs are revolutionizing access to higher education, one student at a time. At one point in our conversation, Roland reaches for one of YPEI’s informational pamphlets on the table and begins to read the mission statement of Yale College: “to seek exceptionally promising students of all backgrounds from across the nation and around the world and to educate them, through mental discipline and social experience, to develop their intellectual, moral, civic, and creative capacities to the fullest.” It’s clear that YPEI is wholly fulfilling this mission. Stockwell echoed this sentiment in explaining her desire as an educator to expand access to higher education to all people.

There have been around three or four courses offered through Princeton’s Prison Teaching Initiative that aim to develop the intellectual and moral capacities of two groups of students simultaneously. ‘Combined courses’ are taught at the prison facility, with students from Princeton’s official campus learning alongside their incarcerated classmates. Greene described how Princeton students interested in criminal justice reform were really pushing for courses like these to happen and that “the Princeton students who have participated in these classes [are] uniformly… humbled by the experience.” She added that students are carefully vetted and “are really invested in making sure all the learning happens in the classroom so that everyone can be on an equal footing.” In addition, Greene added, “just having a larger cohort of people to bounce ideas off of is powerful for [the incarcerated students].” PTI hopes to expand in the future to offer more B.A. courses for credit, much like YPEI does. One key difference between the programs as they currently stand is that YPEI offers Yale credit to their students for summer courses, while PTI classes are taught by Princeton staff and faculty but are all accredited through local community colleges.

The problems of mass incarceration and the disproportionate impact it has on people of color are already intertwined with unequal access to education in communities of color. The War On Drugs, racial profiling, and other discriminatory policies have led to a one-in-three probability that a black man in the U.S. will be incarcerated in his lifetime, compared to one-in-seventeen likelihood of imprisonment for white men in the U.S.; the U.S. also has the highest incarceration rate in the world, according to data compiled by The Sentencing Project. In my conversation with Roland, she touched upon the fact that those in prisons are disproportionately black and brown people. In the prisons in which her program operates, incarcerated people are also disproportionately from the city of New Haven, which in itself has been disenfranchised by Yale. Greene explained how mass incarceration and education are entangled, saying, “People who are incarcerated… have been systematically excluded from education in their past, and so they really didn’t have the tools to survive in the world.” She adds, “giving people those tools and the hope that they can live full productive lives and make it out in the world is a wonderful thing to be able to do.” Indeed, the Yale Prison Education Initiative notes on their website that only 22% of people in state prison have had some form of postsecondary education.

A country failing to provide equally for its citizens will necessarily have problems with the strength of its democracy, and this troubled relationship between incarceration and democracy in the United States is the focus of some of Stockwell’s research and scholarship. She explains, “The U.S. disproportionately incarcerates people who have had fewer educational opportunities than the general population,” which further emphasizes the entanglement of these matters. In part, this is because incarceration disproportionately impacts people of a lower socioeconomic status, and these individuals also have fewer high-quality educational opportunities pre-incarceration. With a Bachelor’s degree becoming the new high school diploma, it becomes difficult to find a steady, well-paying job. Furthermore, the policies mentioned above essentially criminalize homelessness and poverty, creating a direct pipeline to prison for economically disadvantaged communities.

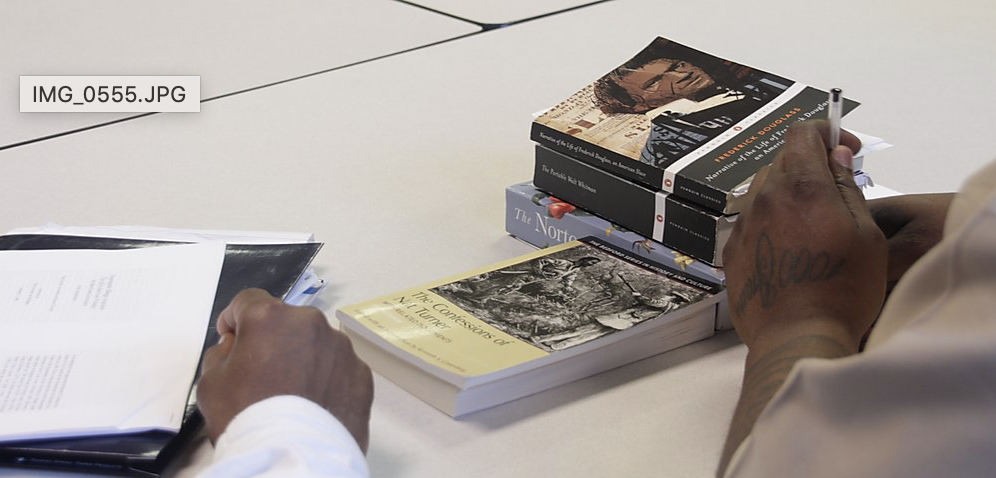

Generally, access to education programs and books serves to build dignity in a system that has become brutal and that cultivates dehumanization. Besides educational and rehabilitation programs in prisons, there are a number of nonprofits across the country focused on expanding access to books and other educational resources. Books Through Bars NYC is one of these groups. Completely volunteer-run, they work to match requests mailed in from people in prison to the books they have collected through donations. They then package and send books directly to individuals. On their website, they state, “We believe literacy and access to reading material is a human right.” This is a right that the U.S. government has continually taken away, cutting funding for education programs in prisons and excluding incarcerated individuals from the federal Pell Grant program. Despite the existence of prison libraries, they are often severely understocked. Author and activist Rachel Kushner expressed her frustration with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) when she responded to questions from the Globalist. She wrote “20 times” to the state librarian, Brandy Buenafe, to try to donate books from Scribner—her publisher—that “the state might find useful for people in prison,” including Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and other acclaimed writers. Buenafe replied in June of 2018 saying she would “review [her] request” and get back to her, but Kushner never heard from her again. She gave this anecdote as an illustration of how the CDCR “has absolutely no concern with providing books or educational materials.”

When it comes to financing for formal education, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 banned incarcerated students from receiving Pell Grants, which are need-based grants awarded to low-income undergraduate students to be used for postsecondary education. Ending the ban on incarcerated individuals would make millions of dollars available to them through these grants. In 2015, the Department of Education began a pilot program called the Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative, which allowed about 12,000 incarcerated individuals to be eligible for Pell Grants. However, this is only a sliver of the incarcerated population. Those who want to pursue an education while behind bars are often unable to, simply because they cannot afford it.

The value of educational access goes beyond a person’s time in prison. Educational rehabilitation programs like PTI and YPEI are shown to greatly improve reintegration outcomes for formerly incarcerated individuals. Now that so many jobs in the U.S. require a college degree or higher, education in prison can make a huge difference in the options people have once completing their sentence. Erin Flowers, the graduate student Math Chair for PTI, wrote to the Globalist, “The most impactful part for me has been seeing how the classes we offer can change the lives of our students while they are in prison, and how it can potentially change their lives for the better once they complete their sentences.” A report released by the Prison Studies Project backed this up with statistics from studies that show nearly unanimously that higher education in prison reduces recidivism, which translates into numerous benefits not only for formerly incarcerated individuals and their families and communities, but also society as a whole.

Nobody should be reduced to a dollar value, though a comparison between the cost of incarceration and the cost of education works to refute the claims of anyone who opposes educational access in prison because of the cost. The cost of educating an incarcerated person is significantly less than the cost of traditional incarceration. On their website, YPEI outlines the high cost of incarceration and compares it with the cost of books for a student—notably much lower: the books and supplies for one incarcerated student during the pilot of YPEI cost $165, versus the $60,000 cost to taxpayers for the incarceration of a person for one year. Additionally, the opportunity to save money on incarceration allows for increased investment in our public education system and in expanding access to higher education—a move that would decrease the number of children disenfranchised by the system and eventually incarcerated.

There are numerous examples of the graduates of prison education initiatives going down impressive paths. George Chocos (‘16 M.Div ‘17 STM) currently works for Georgetown’s Prisons and Justice Initiative; he earned his own B.A. while incarcerated through the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) before graduating from Yale Divinity School. Graduates of the PTI program have returned to Princeton to do summer research with faculty, and Greene described the “tremendously impactful” experience of one formerly incarcerated student who traveled to the Czech Republic for a study abroad research experience, and is now enrolled in a two-year Masters of Social Work program. For these men and hundreds like them, access to education while in prison created the opportunity for them to pursue careers, find jobs, and reintegrate in society. Right now, programs like BPI, YPEI, and PTI are at the forefront of providing this access. However, Jill Stockwell is quick to note that PTI is a program you “don’t want to be around forever.” There is a hope that widespread access to higher education is eventually implemented throughout the country and that issues of disenfranchisement surrounding education and incarceration are addressed through policy and reform.

The debate surrounding access to education and books in prison gets at a bigger question: what are prisons for? Some Republican senators refuse to give up their “tough-on-crime” ideology, but decades of statistics have shown that this is not successful. Though prisons have traditionally been viewed as being a place for punishment, there is reason to believe that the current measures go too far. It may be that taking away someone’s freedom is punishment enough. High recidivism rates across the U.S. demonstrate both that these measures are not acting as a deterrent and also that what is being done in prison does not go far enough in the way of rehabilitation. If the goal of the penal system is to improve the wellbeing of society, then it is clear that rehabilitation programs, including prison education initiatives, should take the place of traditional incarceration.

The United States only needs to look abroad to see the efficacy of implementing higher education programs and other comprehensive rehabilitation programs in prisons. Norway’s system of incarceration has garnered global attention and has proven to be so effective that other countries are beginning to use it as a model. The key is that they focus on rehabilitation and emphasize access to education and health services. As a result, they boast one of the lowest recidivism rates in the world, with 20% of those released from prison being arrested within two years, and their incarceration rate is less than a tenth of the U.S. ‘s. In comparison, 68% of people who are released in the U.S. are arrested again within three years.

Educational rehabilitation programs are just the beginning for the prison abolition movement in the U.S., which embraces these types of reforms and pushes further. As Rachel Kushner noted, “people who are incarcerated also do not have access to their families, to privacy, to dignity, to the right to work, to the ability to make amends for acts of harm.” The groups and activists supporting this movement believe in addressing these issues by reducing or eliminating prisons and the penal system and replacing them with systems of rehabilitation. U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has supported this idea, explaining on Twitter, “We have more than enough room to close many of our prisons and explore just alternatives to incarceration.” These alternatives would work to improve society as a whole by making way for true rehabilitation. Serious prison reforms and shifts in the way we conceptualize punishment and imprisonment in this country are required before the cycle of incarceration begins to break.

Sarah McKinnis is a sophomore in Trumbull College. You can contact her at sarah.mckinnis@yale.edu.