Featured image: browsing books in the Mbabane Library Association Book Exchange (Photo: Kellen Silver).

By Kellen Silver

The main road unfurls like a red carpet from the foothills of mountains streaked with forest fire ash to the bustling city center below. At the bottom of the hill lies Mbabane, the capital of Eswatini, formerly called Swaziland. Fruit vendors line the street overlooking the city’s transportation hub, where kombi drivers in their Volkswagen vans shout their destinations. “Manzini! Manzini! Manzini! Manzini! Manzini!” one rattles off like an auctioneer. Car horns honk as they depart.

A few blocks away, on a side road filled with fabric stores and bank branches, everything slows to a more leisurely pace. Amid the lull of weekend errands, the Mbabane Library Association sits quietly, a small square building painted a muted olive green. The neat white grids on the windows call to mind a pre-1968 British outpost, a ghost of colonial design. A black wrought iron gate spans the archway that leads to two doors inside.

The door on the right opens to a small room of no more than two hundred square feet, filled with neatly organized library books covered in plastic. The door on the left opens to an even smaller room, covered floor to ceiling with secondhand books for sale. Packed wooden shelves of books, aging cardboard boxes of books, haphazard leaning towers of books. There is hardly a cubic inch left unbooked.

As I sit on the floor of this beautifully chaotic room, combing through Shakespearean sonnet collections and pulp fiction paperbacks lying side-by-side, my eyes fall on a weathered hardback. Its cover is scratched and worn, the plastic peeling like dead skin in places, but its interior is intact. In a bubbled green serif, the title reads: “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.” The name sounds vaguely familiar, a teacher’s recommendation floating into my head. I pick it up and turn it over in my hands.

Inside the front cover of the book is a purple stamp, marking a return address, “St. Mark’s High School, P.O. Box 31, Mbabane,” and a date, “1992-01-15”. At the top of the page are the names of two students to whom the book was issued, one neatly printed and one hastily scrawled. I bring the book to the small plastic folding table that blocked half the doorway. “Twenty rand,” the woman says, using the South African currency which is used interchangeably with the local emalangeni in Eswatini. I hand her a twenty, about 1.50 USD, and walk up the hillback toward home.

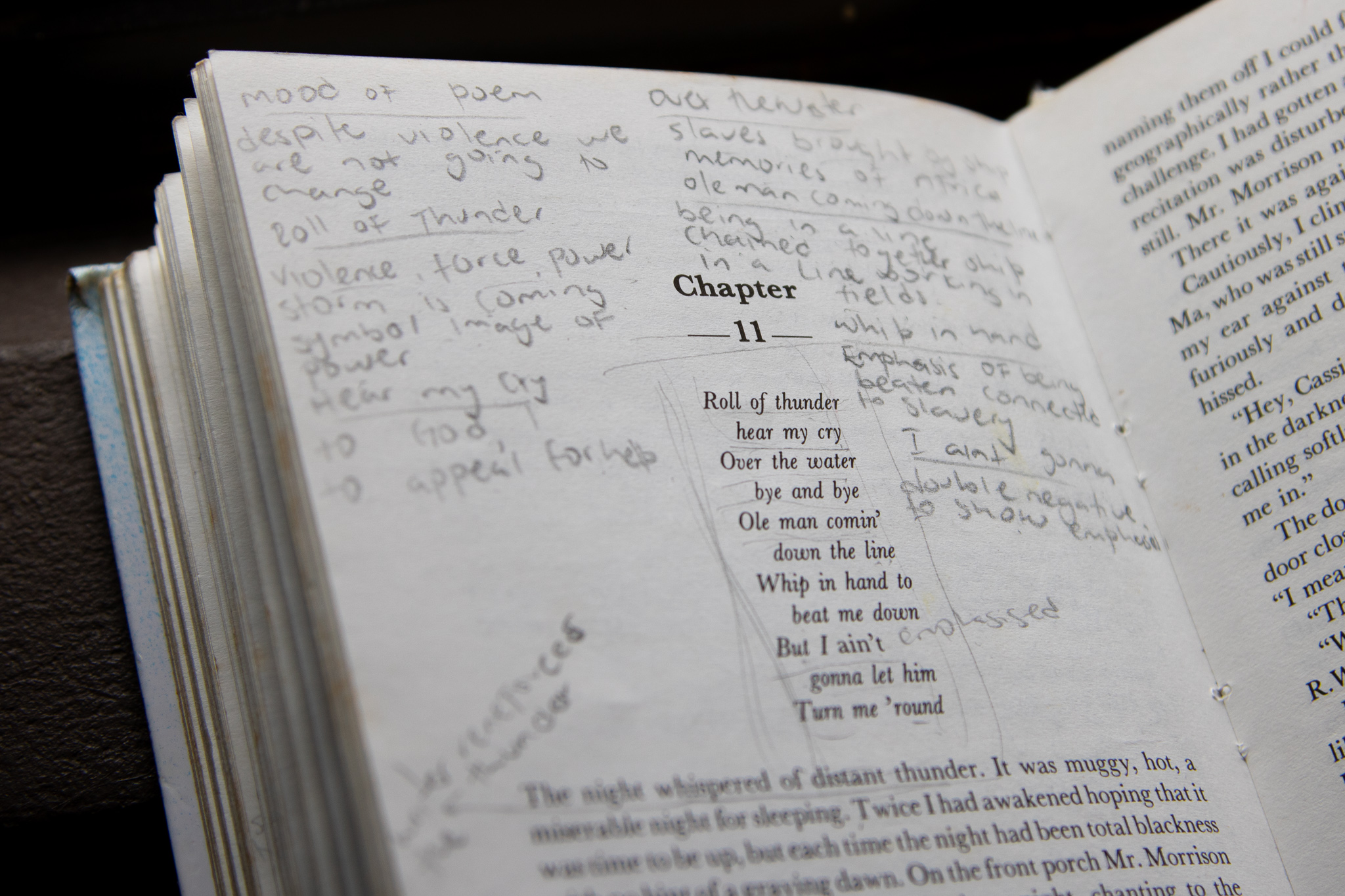

I would start reading on the plane back to the United States, and as I read, I noticed pencil marks in the margins, which had smudged and faded over the years. They started slowly, none on the first page, one on the second, two on the third. But by the end, the notes spilled across the pages, arching over and around paragraph breaks, little arrows snaking around important points.

Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry follows Cassie, a young Black girl in 1930s Mississippi, the middle child of a family of independent farmers living in the long shadow of racism in the South. In the first chapter, the author, Mildred D. Taylor, provides a look into Cassie’s classroom on the first day of school, in which each student receives a copy of the class reading book. The children open their new books excitedly, only to find out that they have been given secondhand books from the white school down the road.

A table in the front of Cassie’s book lists the book’s previous issuances in a two-page spread. Eleven lines list the white students who owned the book before Cassie, the years growing larger and the condition deteriorating with each entry. The last line of the table in Cassie’s book reads issuance: “12,” date: “September 1933,” condition of book: “Very Poor,” race of student: “nigra.” Cassie and her brother storm out of the room to the classroom where their mother teaches, and their mother pastes over the table with a blank sheet of paper. She later loses her job for it.

Despite vast differences in time and place, the similarities between the real world and the world of Taylor’s novel are striking. This school-issued, secondhand copy of Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry found itself in the hands of a young Black girl at a critical time of racial tension, and her notes in the book tell a story of their own.

By 1992, when Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was being taught at St. Mark’s High School, racial tensions in South Africa were coming to a head. Two years later, amid mass demonstrations and global pressure, the apartheid regime would fall. In the decades prior, freedom fighters fled to Swaziland to escape persecution by the South African government, and many sent their children to Swazi schools. Some of these children may have found themselves at St. Mark’s High School, a few seats away, reading a similar copy of Taylor’s novel, taking their own notes. The owner of this book may have been one such child herself.

At the end of the first chapter of Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, and at the end of every chapter thereafter, the student has written a list of notes, streaming in neat lines, covering every inch of the page left where the last paragraph ends:

“Writer is portrail’s [sic] that black families are poor in contrast to the whites.”

“The black school is neglected.”

“Whites are unfairly privileged.”

The student’s notes continue throughout the book. Some are notes about vocabulary: the word “haughtily” gets defined as “full of pride”, and “weather-beaten” as “not in good condition, neglected.” Some distill the finer details of the plot: the student notes that Papa’s instructions to the kids about not going to the bigoted Wallace family’s store “develop a background of racial tension.” Still others note historical context for America in the 1930s, the “time when the trade union started. When a lot of exploited groups stood up for their rights.” Most of the early notes have an air of adulthood, as if the teacher wrote them on a chalkboard, and this student copied them dutifully into her book. I can almost hear the student ask, “Will this be on the test?”

But as the book continues, the notes begin to feel more natural and age-appropriate. The line blurs, and it becomes harder and harder to tell which are the teacher’s words and which are the student’s. On one particularly slow school day, the student writes, “Boring!! Slept for two periods…feel very sleepy, hungry.” Notes like these mix with notes about the text and its commentary as the student engages more and more with the book.

On the last page of the novel, the student has written two notes that are particularly striking. First, she writes, “Segregation – keeping two groups separate; apartheid – separateness,” explicitly noting the similarities in the injustices of the United States and South Africa. And second, at the very bottom of the page, “Whites in SA have very high standard of living/Wallaces are strong coz of the economic position.” Something about these final notes doesn’t read the same way as the earlier ones. They seem to to show the student coming to her own conclusions, drawing connections she may not have seen before. Instead of trying to remember details for an upcoming exam, the student here seems to be writing for posterity, understanding that these lessons just might be more important than they seemed at first.

I don’t think Mildred D. Taylor, writing in the 1970s, expected that her book about the American South in the 1930s might end up in the hands of a Swazi high school student in 1992. Even if she did, I can’t imagine that she would have thought that same book might end up in my hands, a Yale student in 2019, spending a summer in Mbabane. But someone at St. Mark’s High School decided that the lessons of interwar Mississippi could cross the borders of time and space and infuse the lives of young Swazi students, who just might have been sharing a school with freedom fighters. And here I sit, five decades and five thousand miles away, learning from Cassie and from this anonymous student alike, learning about the world as it is, and as it can be, if we’re willing to fight for it.

Kellen Silver is a senior in Pierson College majoring in Global Affairs. He can be contacted at kellen.silver@yale.edu.