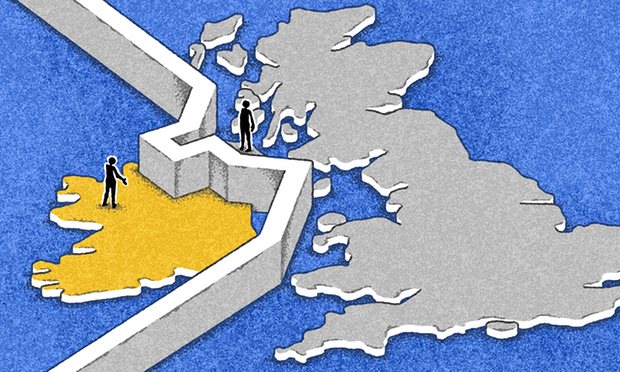

Featured image: the prospect of Brexit is causing stress in Northern Ireland.

By Claire Donnellan

The prospect of Brexit is causing stress throughout the United Kingdom, particularly in Northern Ireland. Brexit would cause Northern Ireland, a part of the UK, to leave the European Union, while the Republic of Ireland would remain in the EU, shattering decades of work to create peace along the border. Ireland was partitioned in 1921, with the southern part of Ireland gaining independence and Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK. The partitioning has led to conflict between Republicans who wish to reunite the island and Unionists who wish to remain in the UK. Physical violence instigated by paramilitary groups reached its peak at the end of the 20th century. This violence was brought to an end in 1998 by the Good Friday Agreement, and the two have since shared an open border, but Brexit could disrupt this by reinstating a physical border.

According to Yale political scientist Bonnie Weir, who focuses on Northern Ireland, there are three main effects of a post-Brexit physical border. First, a sense of identity for people on both sides of the border could be threatened. One accomplishment of the Good Friday Agreement was parity of esteem for Irish and British cultures. Citizens can identify as Irish, British, or both, and since there is little indication that one has crossed the border, it is easy to claim whichever national identity one wants. For many people, this fluidity of identity may be challenged if a physical border is reinstated, as it will provide a clear delineation between British and Irish identity that people living along the border may not conform to. Secondly, a physical border would complicate daily life for thousands by creating slowdowns and annoyances for ordinary people. Lastly, a physical border would provide an easy target for paramilitary violence, reinstigating the violence that Ireland and the UK have worked so hard to end. Professor Weir states that if there is physical infrastructure at the border, the patterns that paramilitary groups have used in the past suggest there will again be violence.

One proposed solution to the issue is a so-called ‘Irish backstop,’ in which Northern Ireland could retain some of the EU’s benefits while the rest of the UK leaves and an open border is included between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Due to the need to avoid physical infrastructure at the border, Professor Weir and others see it as the only viable solution to avoid violence following Brexit. There has also been talk of a vote for reunification of the island, especially following a no-deal Brexit. Professor Weir noted a growing sense of all-island identity, but stressed that there is not enough clarity and too much political anxiety to call for a vote at the moment.

Claire Donnellan is a first-year in Saybrook College. She can be contacted at claire.donnellan@yale.edu.