Japan’s Invisible Minority: Fighting Discrimination through Ignorance

By Kelsey Larson

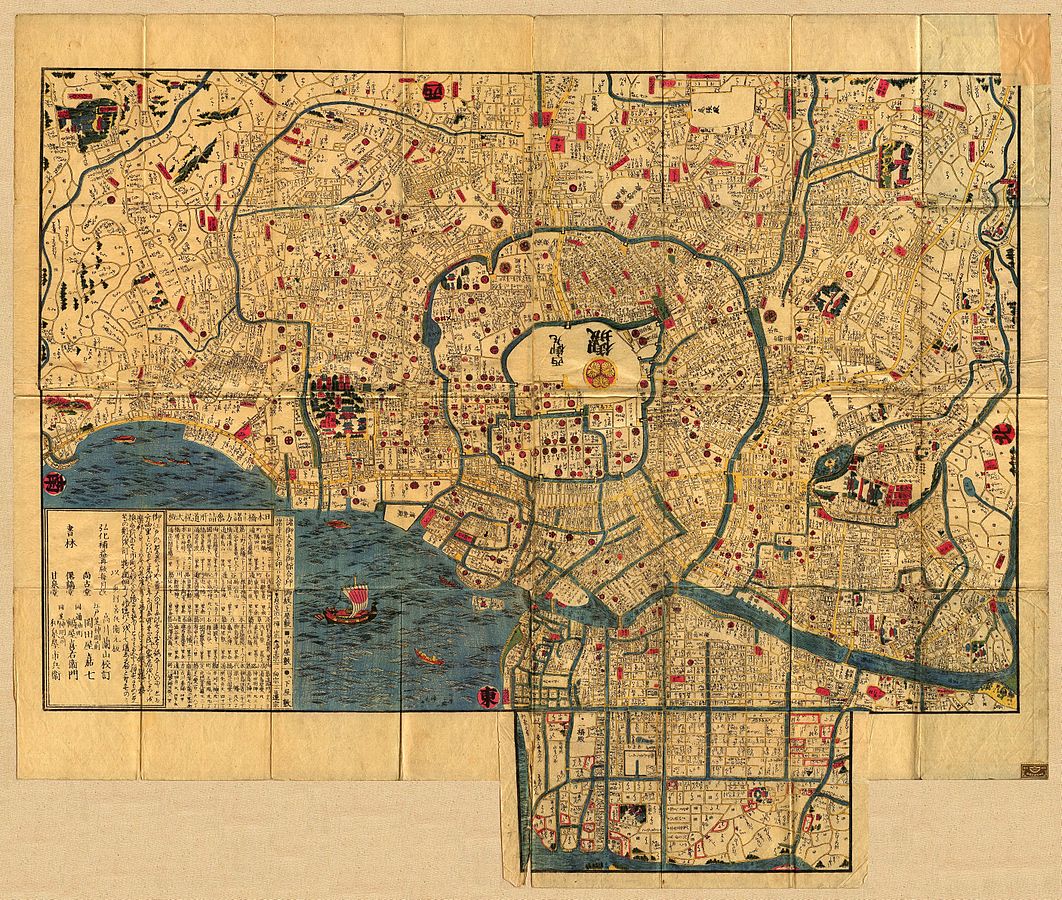

Google thought it was posting an interesting map of historical Japan— until the image on Google Earth was attacked as a “tool of discrimination.”

The optional overlay of Tokyo seemed harmless enough, letting users compare the locations of old samurai residences and merchant districts in the 1800s with the city today. However, it also redrew something that Japanese Buraku activists have spent the last hundred years trying to erase: the lines marking out neighborhoods formerly designated as exclusively for the Burakumin, the “untouchables” who made their livelihoods in jobs—like leatherworking or police work— that were seen as “unclean” because of their association with death or crime. Since many of these districts still have majority Buraku populations, Buraku-rights groups attacked the map as a potential way for employers to identify and discriminate against the modern Buraku. Google took it down within days.

Walking across the lines on the map today, a visitor to a Buraku neighborhood would see the same apartment buildings as in the rest of Japan, filled with people eating the same foods and wearing the same clothes as the non-Buraku nearby. The only difference between these neighbors is the work their ancestors did during the Edo Period, before the caste system locking individuals into social positions and areas of residence was eliminated in the 1860s.

Map of Japan Tokyo during the Edo period, 1844- 1848. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

But abolishing the caste system didn’t abolish old stigmas; the Buraku kept their untouchable status, but lost their legal monopoly on profitable trades like leatherworking, as some other Japanese proved willing to trade traditional notions of “clean” work in exchange for profits. Throughout much of the twentieth century, employers routinely hired private investigators to screen out Buraku job candidates, and parents would forbid their children from marrying Burakumin.

An activist movement arose to challenge these practices in the 1960s—with only limited success. Even today, about 30 percent of Japanese stated in a 2009 survey by the Buraku Liberation League, a Buraku rights group, that they would not support their children marrying a Burakumin.

Few Japanese today genuinely believe the Buraku are inferior or unclean. Rather, as Buraku history expert Professor Jeffrey Bayliss of Trinity College explains, discrimination mostly stems from a “fear of doing anything that makes one seem different.” In one dramatic example, a family interrupted a wedding to beg their son’s Buraku fiancé to call off the marriage because his younger siblings were still unmarried, and the parents feared they’d become unmarriageable with a Burakumin sister-in-law.

To fight this persistent prejudice, the Buraku Liberation League has pushed for laws to lock up the information used to discriminate in the first place. The Japanese government accepted these demands, sharply restricting access to official government ancestry records written in the 1870s—the documents that private investigators used for a century to sniff out Buraku lineage in job applicants and marriage prospects. Even academic researchers have trouble acquiring access.

Beyond concealing birth records, the Japanese government and the Buraku rights movement also use the education system to keep discrimination out of the public eye. Most Japanese schools only briefly mention the Buraku while discussing eighteenth-century Japanese society. Some young Japanese aren’t even aware of who the Burakumin are; in a generation or two, discrimination could be vanquished by the lethal weapon of amnesia.

Since few cultural differences exist between the Buraku and the rest of the Japanese—some traditional crafts and foods, nothing more— many Buraku see the erasure of history as a small price to pay for their total acceptance into mainstream Japanese society. According to Japan-based reporter Philip Brasor, “there’s nothing tying the Buraku together except some vague connection to a community in the distant past.” The gradual erosion of this meager identity is only natural. A few Buraku-majority school districts choose to offer Buraku history classes to help students develop pride in their identities and learn to fight discrimination, but most Buraku have chosen to simply blend in with the crowd.

On Google Earth today, a Buraku neighborhood looks no different than any other. What marks Buraku neighborhoods as different is instead written in the history of the people who lived there and the cultural stigmas they’ve worked to cast aside. Now, to eliminate the last remnants of this old discrimination, many Buraku are choosing to hide their connection to their ancestors’ struggles. In a conservative society—one that fears any hint of deviance—historical distinction is a small price to pay for the prize of acceptance.

Kelsey Larson ’16 is an Economics major in Silliman College. She can be reached at kelsey.larson@yale.edu.