By Catrin Dowd

On an evening in the outskirts of Paris, 12-year-old Cristina and her siblings are dancing to Romanian superstar Nicolae Guta’s greatest hits. Amid an electric accordion’s choppy trills and a four-on-the-floor dance beat, it is hard to guess the Romani lyrics’ meaning. The setting is equally unsettling; Cristina laughs and experiments with dance moves in a small hotel room that serves as her family’s temporary home. Her parents sit nearby as a bespectacled social worker, Olivier Béthoux, puts Cristina’s favorite songs on a flash drive. When the current track ends, Béthoux asks Cristina to translate, and she becomes serious. “Nicolae Guta misses home,” she discloses. “He says, ‘each time I approach the border, my heart cries a little.’”

Cristina, like Guta, knows borders. Her family are Roma, historically known as gypsies or “bohemians,” an ethnicity associated with statelessness. Roma like Cristina cross and are seen to cross several borders: those separating modernity from the past, France from other countries, and plenty from poverty. Cristina transverses other lines. Each day, with the help of Béthoux’s organization, the Federation of Associations providing Aid and Schooling to Roma Children and Disadvantaged Youth (la FASET ), she shifts between Paris and its suburbs, Romani and French, and childhood and adulthood.

Like many 12-year-olds, Cristina is uninterested in ethnicity. She says, and it is true, that she is “Romanian.” Perhaps this choice recalls her previous home, or perhaps, like many in France, she conflates “Romanian” and “Roma.” A minority in Romania, Roma form the majority of recent immigrants from that nation to France. The words have different linguistic roots and describe distinct identities; many Roma in France are not Romanian. Cristina’s Romania is the territory of stars like Guta, a place filled with colorful houses like the rare pink one she stumbled across in Paris. Like countless immigrants, she wonders when she will revisit her native land. Then again, perhaps she feels the stigma that haunts the Roma.

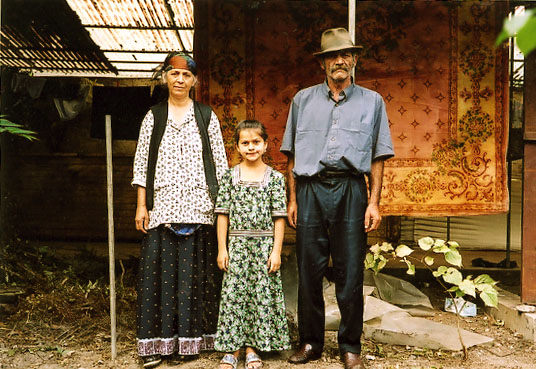

Roma Family, Banlieue, Paris, 2003. (Image courtesy of romeurope.org)

Gypsies have long been unwelcome in France. Linguists trace the origins of Romani to India, but the history of their early migra- tions remains uncertain. Arriving in Europe in the 15th century, they have since been viewed as outsiders, as restless nomads moving across the continent. This idea exploded again in recent international news coverage about the unsanctioned migration of “Roma from Romania” (like Cristina) to France, and their subsequent expulsions by presidents Nicolas Sar- kozy and François Holland. Such expulsions extend a hostile trend that began in 1427 when a troupe of gypsies, circulating around the Parisian outskirts, was barred from the city.

History, however, reveals change. France has, at other moments, embraced real and imaginary gypsies. Many were, in fact, allowed to settle, notably in Alsace-Lorraine. A descendent of these settlers, Django Reinhardt, became the face of 1930s French jazz. In the nineteenth century, Parisian artists, musicians, and writers, often lacking direct contact with Roma, celebrated imagined gypsy transgressions of the norms of work, sexuality, geographic stability, and even musical form. By the century’s end, Parisian artist-types had appropriated the label “Bohemian,” once applied only to Roma. Though Roma faced more exclusion than literature suggests, they gained a mythical place in fiction. In Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, the fictional gypsy Esmeralda inhabits the center of medieval Paris. Had she been real, she would never have been allowed to enter the city. But by Hugo’s day, her people had become a visible Parisian minority.

Over time, the popular image of gypsies, as quintessential Parisian beggars, emphasized poverty. Varieties of people panhandle in Paris, but tourists, influenced by stereotypes, tend to identify all beggars as “gypsies.” A Google search reveals that even in the art world, online galleries have translated the title of François Raffaelli’s painting of a suburban “Chiffonier,” a French rag picker, to “A Gypsy.” The impression that gypsies lived a distinct version of poverty, different from that of other disadvantaged Parisians, produced an ideal of artistic poverty that resists modernity’s demands.

French society generally treats Roma as distinct without recognizing distinctions among them. Roma activists want to change this. Informed by history, they identify the Roma as “a heterogeneous population.” They confront transnationalism and acknowledge the large and largely ignored differences among gypsies who have been dispersed for centuries. Even the Romani language, the most uniting feature, has over 60 dialects. The descendants of the gypsies who came to medieval France might have little in common with today’s Romanian immigrants. But as ethnologist Martin Olivera explained, although there are 500,000 people of Roma origin in France, the media deploys the word “Roma” exclusively to describe the 15,000 recent immigrants from Eastern Europe. From 2008 to 2012, French journalists tended to identify Roma as such in stories rife with suburban shantytowns, juvenile delinquency, underage marriage, and unschooled children. Sociologist Olivier Peyroux affirmed that this “equation of ‘Roma’ with ‘poor’ is a cliché and an obstacle to immigration.”

This has led to a vicious cycle of exclusion leaving Roma immigrants with little choice but to exploit the classic image of the Parisian beggar. In 2007, when Romania and Bulgaria joined the European Union, France established restrictions on hiring their unskilled workers for a seven-year adjustment period. These laws appeared to target Roma, who often lack professional training. Unemployed and unable to apply for jobs, Cristina’s mother found that her most lucrative option was to go begging in Paris, armed with her baby and her most colorful scarf. The vicious cycle may soon be ending. Since January 1st, Romanians and Bulgarians can work in the entire European Union without demanding a visa or work permit.

Cristina, like her mother and many other immigrants, seeks opportunity in France. Upon arriving in Paris about two years ago, they moved into a phone booth near Bastille. Although there was room for the family to lie down, it was cold and difficult. Life was lightened by old friends; Cristina describes Bastille as “little Buzau” because many people from her hometown live there informally. To further combat misery, Cristina threw herself into accomplishing a goal. Romania had provided her only two years of schooling, but living in a great city, even if in a telephone booth, was a chance to start again. Cristina became a figure in the neighborhood, posing a one-word question- “school?”- to passersby. This brought her family into contact with FASET and Béthoux.

Gypsies may lead more sedentary lives than popular lore suggests, but with globalization the entire world has become more nomadic. Béthoux and other Frenchman have visited Romania, and familiarity with gypsies there encouraged activism at home. Ethnologist Olivera, a writer and the founder of the nonprofit Streets and Cities (l’Association Rues et Cités), went to do research for a doctorate; Julien Radenez, a teacher and linguist involved in FASET, investigated the Romani language and circus art. When Béthoux arrived on a volunteer trip, he connected with many Roma. Seeing gadjé (the Romani term for non-Roma) Romanians staring at him, this white-haired Frenchman liked to imagine them thinking, “Who is that bizarre gypsy with the glasses?” With a cheerful personality, a strong faith, and a desire to do good, he became involved in FASET.

An efficient administrator, Béthoux became secretary general and helped coordinate FASET’s main operation: the truck schools (camion-écoles). Radenez and his colleagues drive into Paris’s poorer suburbs, to Pantin, or Bobigny, where Roma live on open plots of land, and FASET’s bright blue vehicles are soon filled with giggling youngsters who get a snack and lessons in everything from French to puppetry. Despite being an integral part of FASET’s work in the Paris region, camion-écoles have limited potential. The mayors of various constituencies may extol the camion-écoles as a clever solution, but FASET organizers like Radenez and Béthoux regard them with frustration, knowing that these classes a few times a week exist partly because governments are not more energetic in providing “real” schools.

Cristina, like Guta, knows borders. Her family are Roma, historically known as gypsies or “bohemians,” an ethnicity associated with statelessness. Roma like Cristina cross and are seen to cross several borders: those separating modernity from the past, France from other countries, and plenty from poverty.

Inspired by Cristina’s motivation, Béthoux is testing a different approach: individual accompaniment. School is complicated, and not only because of homework. Children need addresses, places to sleep, bank accounts, tetanus shots, transportation, technology for homework (and, yes, music-listening), translators if they do not speak French, and hands to hold if they are young. Although schooling is obligatory for everyone between the ages of six and sixteen, immigrant and French children alike slip through the cracks. For Roma, according to Olivera, “there is always a ‘but;’” He means that it is convenient, from an administrative point of view, to just say ‘but they are gypsies!’” This seems like an activist’s exaggeration – the school system, after all, officially ignores ethnicity – but it tallies with Cristina’s experiences. Applications for a lunch scholarship disappeared into the confusion of city hall, and Cristina’s five-and-a-half-year-old sister was refused, for being too young, by an elementary school that accepted an underage American pupil a week later. Béthoux combats this with the help of journalists; FranceCulture and MediaPart have recounted Cristina’s journey.

It takes an army to cross such frontiers, but thanks to perseverance Cristina has been in school for over a year. She started in an UP- E2A- essentially a one-room school house, despite its futuristic name, in which students learn French as a second language, and she is now in middle school. She speaks enthusiastically about endangered species and the school play; less so about technology and English. She has received a practical, immersed language education that is somewhat unusual in the memorization-based French system. She has learned not only to speak French but to imitate classmates’ accents and to translate quickly into Romani. She knows the entire Paris region, its most downtrodden and its most educated people, its schools, subways, phone booths, and hotels. She has made up a song listing the 46 stops on the RER A, a subway line that spans about 70 miles.

The RER crosses under the boulevard périphérique, the famous autoroute that separates the city of Paris from its surroundings. More porous than the medieval walls that barred Cristina’s distant kin in 1427, it goes unnoticed as she glides beneath it on the RER. Yet Cristina has gotten to know the RER making a similar journey to that of the ancient French gypsies. Under the auspices of Paris’s public housing assistance, her family found themselves living in various suburban hotels. The program provides shelter by using space efficiently, but its beneficiaries deal with the uncertainty of not knowing where they will live from week to week. Many of the hotels that volunteer vacancies are essentially truck stops. Smelling of cigarettes and surrounded by 1970s skyscrapers that appear as alien and artificial as an electric accordion sounds, these spaces are intended for still other kinds of nomads, not for residents and especially not for student residents. Cristina would leave her distant hotel room with a FASET volunteer at 6:00 a.m. to start school at 8:00. Her family sometimes considered a caravan or houseboat, but contrary to myths they dream of a “maison stable” (“stable house”). These were some of the first French words they learned, soon after “école” (school). The Paris City Hall was able, after nudging from Béthoux, to procure stable lodging because Cristina was in school. They live in the Essonne, still far from the center city where Cristina studies and her parents spend their days; but with Béthoux’s Sunday visits to accom- plish the important task of “keeping everyone’s spirits high,” Cristina remains motivated.

The end to restrictions on hiring Bulgarian and Romanian workers has further lifted the family’s spirits. But it has worried others; Le Monde recently documented fears that immigrants will “invade a saturated work market and siphon off social assistance.” Cristina’s family has indeed benefited from French assistance programs, but their greatest asset has been their daughter’s determination. Béthoux comments that Cristina is “becoming a young French woman,” reflecting a central goal of the French school system. While Cristina has made the French language her own, she has also adapted its many flavors in a manner that echoes the evolution of the Romani language, developing as the gypsies traveled and gathered words from Sanskrit, Armenian, and many Latin languages. Her story fits the newspaper descriptions, deplored by activists, of a gypsy family begging, living in precarious conditions, and mostly sticking to themselves. It also exemplifies the sacrifice of families and their desire, if given the chance, to find a physical and social place in France. Béthoux does not know to what extent this desire will supersede old customs; “Cristina might get married when she is 17.” But standing on an RER platform on the way home from Cristina’s family’s hotel, he acknowledges that it is the action of crossing a boundary, rather than the destination, which lightens the process: “even if that happens, she and France will have learned from her experience in school.”

Catrin Dowd ‘15 is a French major in Branford College. She can be reached at catrin.dowd@yale.edu.