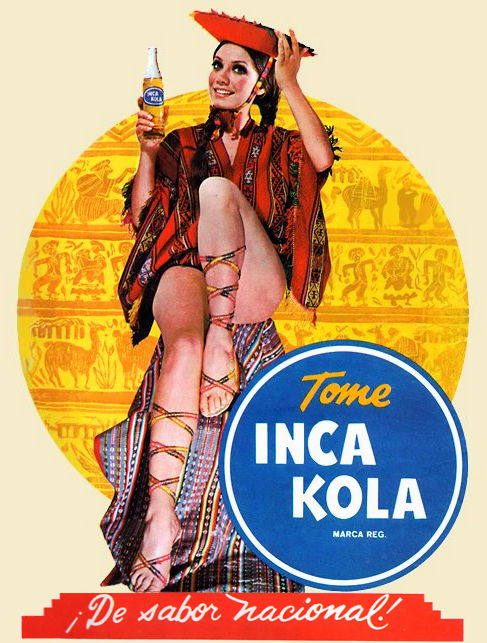

[aesop_image img=”https://live-tyglobalist.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/wikimediacommons2.png” credit=”Wikimedia Commons” align=”left” lightbox=”off” caption=”Peru’s most venerated soda company, Inca Kola, markets its product line as an essential element of Peruvian national identity.” captionposition=”left”]

Soda pop and local religion in Latin America

If Catholicism, witchcraft, and mercantilism were to have a love child, it would look something like the church of San José Bautista in Chamula, a town in the Mexican highlands of Chiapas. The church, built in the simple curves of the Spanish colonial style, overlooks the main plaza of the small town, a pretty but uninteresting landmark. Inside the church’s whitewashed walls, though, hides one of the most fascinating examples of syncretic fervor in Latin America.

Tourists may enter the nave for only fifteen pesos (a little less than a dollar). The single, large, dimly-lit room smells strongly of the pine needles and copal resin holders that cover the floors and burn in niches on the walls. The dozens of figures of saints all grimace, perhaps attempting to embody the essence of martyrdom, or disapproving of the gaudily colorful robes they have been clad in. It is likely that they would also decry the rituals taking place in the middle of the room, where local medicine men attempt miraculous healings through the sacrifice of brown chickens and the drinking of homemade spirits. As is common in provincial Mexico, locals have intertwined indigenous Mayan tradition with the rigors of Catholic dogma. At Chamula, a third set of beliefs has joined the fray: capitalism.

Right next to the pine needles and copal resin burners, hundreds of empty bottles of soda litter the floor. Some of them belong to local brands, and others are labeled Pepsi, but the overwhelming majority of bottles are branded with the red and white calligraphy of the Coca-Cola Company. Everyone inside the church—the chicken-wielding shamans, the ill children, and the chanting followers—is drinking Coke.

The town’s bizarre obsession with America’s favorite soft beverage began when distributor Javier Lopez Perez introduced the drink to Chamula in 1962. Shortly after, some shamans started to believe that pox, a homemade sugarcane rum and a vital part of sacred rituals, should be drunk together with Coke. The idea seems to have spread by way of religious diffusion, so that the local Tzotzil faith now claims that drinking Coke allows the consumption of greater quantities of pox, increasing the purifying effects of the liquor. The gassy beverage also induces burping, which supposedly releases a person’s spirit, allowing it to rise up and carry messages to the heavens. In Chamula, drinking Coca-Cola literally allows you to commune with God.

In last half-century, Chamula’s Coke craze, seemingly a result of local superstition, has had very real consequences for the town’s inhabitants. A can of Coke costs fifty cents in Mexico, approximately the daily income of the average resident of Chiapas. Yet, as shamans push for the drink’s use in ritual purifications, healing processes and prayer circles, Chiapas’ daily per-capita consumption of Coca-Cola products has climbed to a staggering 2.25 liters, more than five times the 0.4 liter national average. Chiapas also has one of the highest rates of malnourishment in Mexico.

The monopoly over the establishment of local traditions commonly enjoyed by spiritual leaders in impoverished areas has granted shamans immense religious power, power that they are using for economic gain. In Mexico, the position of shaman has become virtually interchangeable with that of the cacique, or party strongman, meaning these leaders hold influence over both the religious and the political spheres. Representatives of the Coca-Cola Company are perfectly aware of this, as well as of their product’s popularity in Chiapas, where they offer a bigger, half-liter bottle size unavailable in the rest of the country. Within Chamula, the appearance of a competing group of store owners hints that Pepsi representatives have also been drawn in by the high-profit promises of local religion. Both companies are now trying to establish contracts with the caciques who, in exchange for political representation or hefty allowances, help convince their followers of the superior purifying powers of one drink or the other. Patronized shamans also provide shopkeepers with free soda products before regional elections if the merchants agree to endorse certain candidates, thereby helping caciques maintain their status.

The town’s first Coca-Cola distributor, Javier Lopez Perez, doubled as an extremely powerful cacique, having come from a long line of politically connected shamans. Although the details are unclear, it seems that it was Lopez Perez who started the rumors about the mystical effects of Coke. As the belief spread, locals would walk many miles to buy the dark drink, and Lopez Perez became immensely wealthy. In 1981, he used half a million pesos of his newfound riches to fund the brutal torture and assassination of Miguel Gómez Hernández, a leader of the Totzil Evangelic Church. This effectively banished Christian priests from Chamula, allowing Lopez Perez’ own brand of profitable religion to run rampant. His descendants continue to be Chamula’s Coke distributors and are the wealthiest residents of the town.

More than 30 years later, similar rackets continue to mix Coke with blood. In Chiapas’ town of Mitzitón, for instance, the combination of religion, politics and Coke unleashed a deadly conflict after José Santiz, the town’s shaman, local party leader and sole store owner of the town, struck a deal with Coca-Cola representatives. In exchange for free refrigerators, chairs, advertisements, and other store paraphernalia, Santiz agreed to sell twenty packs of Coke a month. He attempted to achieve the quota by forcing the town’s inhabitants to buy certain quantities of the product, wielding over them the threat of store closure. The conflict turned violent when thugs were hired to intimidate challengers, and many families left Mitzitón.

Yet not every resident of Chiapas has responded compliantly to the Coke rackets. Outraged by the vicious impunity of the caciques, a small number of neighboring towns, such as the village of Xoxoxotla, have decided to completely banish Coca-Cola products from the local stores. Yet in most of Chiapas, the bizarre partnership between shamans and beverage companies has hooked the population. In Chamula, especially, the thirst for cola remains unquenched. Coke is used as medicine and is gifted to celebrate baptisms, marriages and funerals. Six-packs are offered as payment to settle simple claims in court. An enormous Coca-Cola billboard now welcomes tourists to the town. Injected slowly and surely by caciques into the heart of local tradition, the dark drink now runs within the veins of Chiapas.

***

More than 2500 miles away from the church of San José Bautista, on a field in the Sacred Valley of Urubamba, in Cusco, Peru, Jesús Orozco prepares a time-honored ritual. Dressed in the colorful woolen hat and long poncho of the Peruvian shaman, he exhaled long droughts of tobacco smoke and directed his eyesight mystically towards the peaks of a snow-capped line of mountains. A large group of tourists, wide-eyed and expectant, surrounded him. Orozco was delivering a “Payment to the Earth,” an ancient Andean ceremony popularized somewhere around 5000 A.D, millennia before the rise of the Incas. Reciting soft Quechua in between breaths of smoke, Orozco made his offering to the Pachamama, or Mother Earth, so that she might quell the spirits of the mountains and bring good fortune to those present. One after the other, he packed his gifts in a bundle to be burned and buried later: coca leaves, gold thread, potatoes, confetti, a woven alpaca shawl, cigarettes, a colorfully painted pot. Then, amidst the whispers of the visitors and the clicking of camera shutters, Orozco made his final offering, climatically spilling onto the dirt a jar of corn beer and a liter-bottle of Inca Kola.

Invented by British immigrant Joseph Robinson Lindley in 1935, Inca Kola is Peru’s leading soft drink, capturing close to a third of the country’s soda market. Fiercely yellow and with a taste described by most foreigners as akin to that of Bazooka Bubblegum (though lemongrass is one of the primary ingredients of its mysterious recipe), the quirky beverage’s success might seem improbable. Yet, Inca Kola is as venerated in Peru as Coke is in Chiapas. In many ways, the unlikely success of a soda that looks like urine and tastes like chewing gum owes much to the phenomena of nationalistic mysticism, represented by people such as Jesús Orozco.

Orozco’s modernized version of the “Payment to Earth” could very well have belonged to an Inca Kola commercial. Throughout its history, Inca Kola has pursued a marketing strategy that aims to position the beverage as an essential component of Peruvian identity. Ever since its founding, the company has used slogans such as “the taste of Peru,” “the drink of our country” or “the national flavor.” Geometric designs typical of ancient Peruvian pottery decorate Inca Kola bottle labels. The company’s commercials attempt to highlight Peruvian creativity and folklore, combining local slang, breathtaking landscapes and historical sites. Inca Kola’s attempts to link its product with Peruvian heritage have been so successful that the sale of a considerable proportion of shares to Coca-Cola, who aimed to control a larger slice of the Peruvian beverage market, prompted a decrease in Inca Kola sales, accompanied by a boost in the popularity of copycat yellow sodas. The general consensus, as detailed in Peruvian newspaper articles, was that the sale had de-nationalized a beloved brand.

[aesop_image img=”https://live-tyglobalist.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ceremony-2.jpg” credit=”Micaela Bullard/TYG” align=”right” lightbox=”on” caption=”Orozco packs a liter-bottle of Inca Kola among a bundle of gifts to be burned and buried later, so that Pachamama may bring good fortune.

” captionposition=”right”]

Orozco’s pouring of Inca Kola onto the floor of sacred sites speaks of a similar story of branding success, of the intertwining of local religion and corporate goals. Just like its gastronomy, its biodiversity and its archeological sites, Peru’s religious syncretism has played a vital role in the development of the country’s identity, combining indigenous heritage with Spanish tradition and African influences. This reality has not been ignored by Inca Kola’s marketing team; one of the brand’s most iconic billboards involved a “retablo,” a local interpretation of the nativity scene where herds of llamas and Andean deities bring offerings to the baby Jesus. Shamans commonly feature in Inca Kola commercials, uncapping bottles of soda and partaking in rituals. They share the essence of Peru with visiting tourists, both ritually, through chanting and smoking, and tangibly, by passing around glasses of the familiar golden liquid.

Orozco says that his use of soda in traditional rituals has a lot to do with the role of shamans in modern society. The position of cacique, he argues, was born out of a need to represent the people, the “communal aura,” in both the spiritual and the physical world. Embracing new Peruvian traditions, he feels, is necessary to maintain the popularity of local religious leaders in the midst of societal change. Orozco believes Inca Kola has overtaken chicha, fermented corn beer, as the national drink, and he is thankful for it; Inca Kola’s representations of shamanic rituals are good for business, and the unusual drink is attractive to the visiting tourists who supply the majority of his income. Like coca leaves, alpaca wool, and potatoes, Inca Kola is “cheap, good and Peruvian. What’s not to love?” In Cusco as in Chiapas, the taste of superstition seems to be changing, and it can either be dark brown and woefully dense, or bright yellow and artificially sweet.

Micaela Bullard ’18 is a tentative Latin American Studies major in Calhoun College. You can contact her at micaela.bullard@yale.edu.