Featured Image: Adult education students listen at Centro Latino in Chelsea, MA a suburb where the Latino population has boomed. (Photo by David L Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

By Victory Lee

In my previous two articles, I have discussed the dire conditions that drive Central American migrants out of their homes and the threats that they face––uncertainty, abuse, and even death––in their desperate escape. However, even those who survive these tribulations are not guaranteed a new, happy life that they dream of. For many migrants, the American dream is often shattered by the bitter reality they face as they resettle into a foreign world.

In high school, I had the opportunity to teach ESL (English as a Second Language) to a group of adults at the Hispanic Center. When I would greet the class asking, “How is everyone?” the most frequent answer I received was “very tired.” They would often tell me about how they came straight from a night shift or working overtime on a Saturday overtime. After a full week of exhausting work, they still brought themselves into the classroom to learn English. Unlike for us to whom a second language is a useful talent or an impressive addition to the résumé, English is a matter of survival to them. Anxiously filling out important documents in fear that something might go wrong, frustratingly trying to understand their boss in the workplace, figuring out how to communicate with their U.S. born children. Every step of their new life confronts the barrier of this new and foreign language.

Having crossed the physical border, they face yet even more walls in finding their place in the foreign country. The Pew Research reported in 2018 that four-in-ten Latinos say they have experienced discrimination in the past year. Three-fourths of these incidents were reported by migrants and second-generation Hispanics. They include most notably being criticized for speaking Spanish and being told to go back to their home country. Those who label their migration “an invasion” find their broken English to be an easy target. Migrants are often degraded for their lack of fluency in English and insulted for their language and culture.

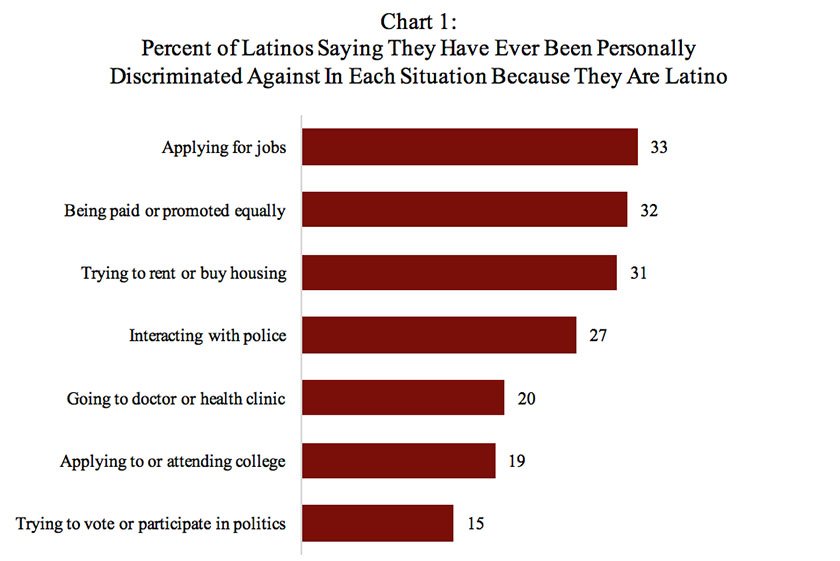

Discriminatory practices are especially commonplace in the workplace. A poll by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that over thirty percent of Latinos have been personally discriminated against in applying for jobs because of being Latino as well as in their payment and promotion at work. Paradoxically, many face barriers to stable employment, the very reason they came to the U.S. in the first place. Due to the difficulty of communicating in English, they often serve in physical jobs which require minimal use of the language and, correspondingly, have low pay. These low-paying jobs also mean that the remittance payments (the money migrant workers send to their families back home, which is a key factor of economic growth in Central American countries) are restrained, resulting in less economic return for the Central American nations and ultimately more economic depravity and increased urgency to seek economic opportunities through migration. In this way, then, discrimination against Latinos and the reluctance to accept them contributes to what necessitates their initial economic escape to the U.S.

Source: NPR/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views of Latinos, January 26 – April 9, 2017.

There are so many more challenges that migrants face as they proceed through resettlement, but we already see a common theme: lack of education, especially that of the English language. Therefore, support for more well-designed education and English lessons for Spanish-speaking migrants seems to be an intuitive solution; this is beneficial not only to the migrants themselves but to the American society as a whole. David Campos, professor of Education at the University of Incarnate Word, details that improving Latino education will invigorate the economy, as well as encourage migrants towards greater civic engagement and social contributions.

Education can be the structural solution to the fundamental root causes of migration I had identified in the first article. For instance, rather than a one-time aid package, increasing state support for GED and English education for migrants may pave the way to more stable jobs, which will raise remittance payments sent back to support their families back home and contribute greatly to more permanent relief of poverty, the major migration factor in the Northern Triangle. In the organizational level, replacing the disconnected or repetitive lessons using handouts with a standardized ESL curriculum may help students learn and review the material more efficiently as well as save balance the work schedule with English learning.

On the other hand, while education can be a crucial systematic reform, it cannot be a magic bullet. Even after a productive ESL curriculum and state support for migrant education are implemented, the inherent xenophobia in our society will not be automatically eliminated. Someone fully proficient in English is often discriminated against because of their accent, race, etc. Therefore, we must not simply aim to change the “undereducated state of migrants” but more importantly our own attitudes toward them. When a job applicant is rejected because of their accent, it is not their pronunciation but the mindset of the interviewer that must be addressed. Education can only effect significant improvement in migrant status once it is accompanied by change from within the American society.

Victory Lee is a first-year in Ezra Stiles College. You can contact her at victory.lee@yale.edu.