Today’s challenges to humanitarian work, from a former president of Médecins Sans Frontières

By Selena Anjur-Dietrich

[divider]

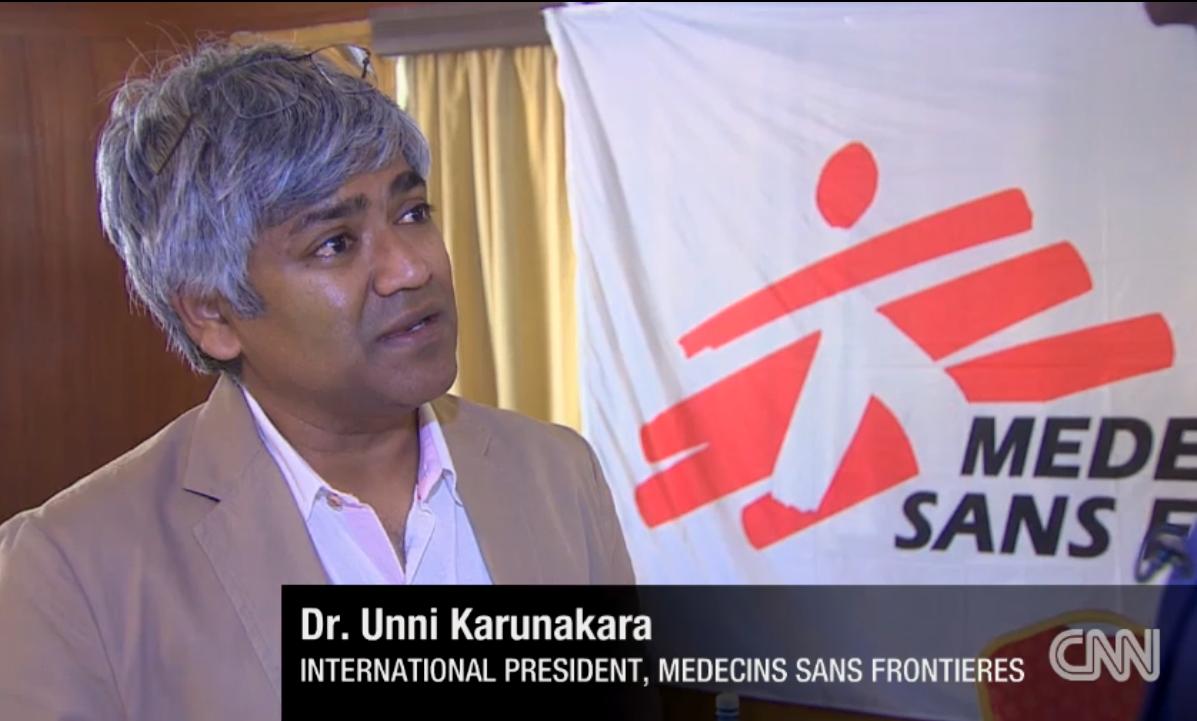

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n October 3rd, 2015, US military forces bombed a hospital in Kunduz, Afghanstan, killing 42 staff and patients and injuring many more. While Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) or Doctors Without Borders, the humanitarian organization operating the hospital, condemned the attack as a war crime, the subsequent US military report cited errors related not to the Geneva Conventions, but to its US Special Forces Rules of Engagement (which are classified and not available for public scrutiny). According to Dr. Unni Karunakara, former president of MSF, the attack represents a blatant disregard of international conventions that dictate rights of civilians, prisoners of war, and soldiers otherwise incapable of fighting, with impunity.

“Just because it was an error doesn’t make it any less of a war crime,” he noted at a small dinner of 20 students in Pierson Fellow’s Lounge on Monday, February 1st. At the same time, Karunakara conceded that the United States is not alone. It is not the case that every country considers itself to be bound by every international law – to take one example, India is not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention – but even some signatories of the Geneva Conventions state or demonstrate that the Conventions do not bind their actions. Karunakara cited Denmark’s hotly debated refugee asset seizure law as a recent example of the country’s ongoing diversion from UN conventions, as well as various actions by Russia and other countries that endanger refugees’ protected status. International Humanitarian Law forms the foundation for humanitarian action, and any inconsistency of attitudes and its application has very real consequences for their continued operation, compounded by the fact that hospitals are, in practice, no longer guaranteed safe zones. “In the last 10 years, we have seen a 250% increase in deaths of humanitarian workers and also journalists,” Karunakara explained, adding, “If the Geneva Conventions are dead, what do we have left?”

MSFs neutral stance further compounds the challenges it faces as a humanitarian organization. While other organizations might turn to government assistance in ensuring the security of staff and patients, MSF’s dedication to independence and neutrality precludes that option. MSF currently provides medical care and supplies to over 10 million people in 70 countries, supported exclusively by individual and corporate donors, with individuals’ contributions amounting to 90% of funding. Emphasis on impartiality and on continual communications with whatever authorities may be present on both sides is essential for maximizing access to conflict zones, protecting recipients of care from retribution for disproportionate care, and for creating potentially sustainable models for medical care. This especially applies in cases with an international consensus on aggressor and victim parties, such as was the case for MSF’s engagement during the Rwandan genocide. In responding to critics of this stance, Karunakara often reaffirms that the mandate of MSF is “people to people; it is not meant to be government action. We are not a human rights organization. We privilege human lives over human freedoms”.

MSF currently faces two other categories of challenges to its mission: obstacles to patient access (increasingly difficult in conflict regions such as Syria and Somalia), and ensuring that upon arrival, the medical care is appropriate and viable for those patients. “Fridges are first world technology,” Karunakara explained, referring to the need for heat-resistant vaccines in areas lacking electricity, for example. He also warned of rampant profiteering in the pharmaceutical industry, which renders vital treatments inaccessible to poor countries, such as expensive HIV drugs in the ‘90s.

Anthropologists and lawyers form an important part of MSF staff, identifying issues such as differences in health-seeking behavior – “People don’t feel empowered enough to ask for healthcare”, Karunakara mentioned, referring to societies with strong social or ethnic hierarchies – and alternative medical theories. MSF staff comprises approximately 10 local members for every non-local, providing the necessary expertise in cultural competency. Taking the Ebola epidemic as an example, Karunakara said, “People have a very different understanding of how disease is transmitted so the language has to be articulated differently. We cannot be snobbish about western ways of looking at disease if you want people to be healthy.”

As the reality of on-the-ground adherence to International Humanitarian Law changes, organizations such as MSF must find new ways to maintain the security that impartiality previously guaranteed, in order to continue providing essential aid where it is most lacking.

[hr]

Selena Anjur-Dietrich is a junior Cognitive Science major at Ezra Stiles. Contact her at selena.anjur-dietrich@yale.edu