By Sung Jung (John) Kim

[divider]

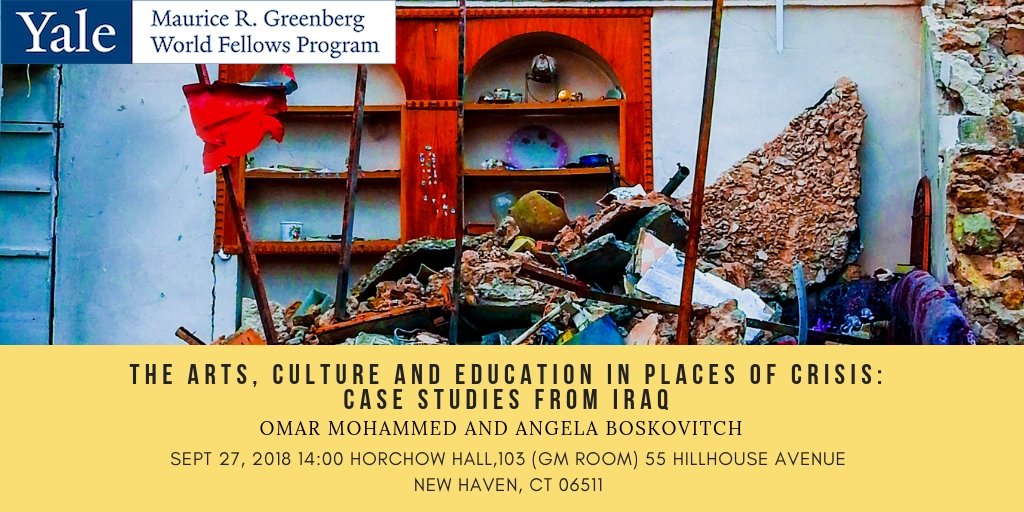

On September 27, 2018, Omar Mohammed, an Iraqi historian and journalist, and 2018 World Fellow, and Angela Boskovitch, art director and freelance journalist reporting on the Mediterranean and the Middle East, both gave a presentation about “Arts, Culture and Education in places of Crisis: Case Studies from Iraq.” Mohammed began the talk by putting the audience in the political and historical context of Iraq. Just that day, an Iraqi social media star and female activist Tara Faris was killed by an unidentified gunmen in Baghdad. Two days before, Soad al-Ali, a young female activist, was shot dead by a masked gunmen for her public demonstration demanding better services in Basra, a Southern city in Iraq. Residents protested the government’s corrupt leadership citing it’s failure to provide basic services, such as clean water.

This violence and conflict in the region, unfortunately, is not new for the Iraqis. Mohammed points out that this tension can be traced back into history, where elements of division in the country are transparent in the history, arts, culture, and education of Iraq. The different ethnic and religious groups in the region – the Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, Turks – all sought power over the regions. The Sunni-Shia conflict further complicated the political sphere of the country. With different demands from different groups, the government was unable to accommodate them led to protests and coups that replaced regimes. From the successful 1958 coup d’état, famously known as the 14 July Revolution, that placed Abd al-Karim Qasim into power, to the unsuccessful protests against Saddam Hussein, Iraq has endured decades of political instability. When the Shia and Kurdish Iraqis led uprisings against Saddam Hussein, they were repressed by the Iraqi security forces and were attacked using chemical weapons leading to civilian deaths.

According to Mohammed, “art in Iraq was politicalized…hijacked by the government.” From 1980 to 2003, art production was “dominated by the government” and used to “serve the government, the regime.” This inevitably led to a lack of diversity in the arts: artists “were always producing the same art, the same conflict.”

Even aspects of the education, such as literature in Iraq, was controlled by the government and used as propaganda. For example, literature at that time focused on the ancient Arab-Persian conflict, often portraying Iran as its enemy.

However, Mohammed noted that after the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iraqis were hopeful that “art would be the heart of new Iraq,” and that the new government would no longer restrain the free expression of artists.

Unfortunately, this was not the case. Artists became the target of “many jihadist groups, extremists on both sides” of Islam. Hundreds of artists were assassinated for creating art because it was seen as a secular tool, which according to jihadists was “an enemy of their beliefs.” In fact, religious paintings were also considered secular and thus in conflict with the beliefs of the jihadists.

In 2003, art was once again politicized. But this time, it was used to illustrate the sectarian conflict between the Shia and Sunni Muslim groups.

These uninviting environments for public art led many artists to leave the public spaces to pursue art in a safe, private place. Art, which was once used as a way of free expression, was now subjected to societal and political guidelines. Thus, artists no longer felt safe to publicly share their artworks.

After Mohammed’s presentation, Boskovitch broached the topic of Iraq’s isolation from the world and expanded to how art has been used to bring different ethnic and religious people together. She explained how young Iraqis are eager to connect with the world, but lack the opportunity to travel outside of their country. Boskovitch also noted that “most young people experience the world through the internet…and they share messages with people all around the world and try to understand what’s happening.”

For these young Iraqis, film festivals were and remain especially crucial in connecting them with other Iraqis and with the world. According to Boskovitch, theater has been the most influential form of art since 2003. Film festivals were also ways to connect with the country’s past history. According to Boskovitch, “Not only were people disconnected from Iraq, but Iraqis inside of Iraq were disconnected even from their own history.” She further noted that “so much has been lost…so much has been burned.” Many historical elements and artifacts of Iraq have been destroyed and unable to be recovered.

Furthermore, in Iraq, it is challenging to hold sustained, annual cultural events. The International Iraq Short Film Festival, the first international film festival in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein, was held in 2005. Eight years later, the third one was held in 2013. “It’s extremely difficult to find venues and to find funds. Sometimes, the government can provide funds, and sometimes, they do not.” Boskovitch also mentions that the country does not have a tradition of corporate funding. Although telecommunication companies and international organizations occasionally help fund the cultural events, it is very difficult to hold major film festivals without the government’s support.

Film festivals have therefore served as avenues for Iraqis to connect with one another as well as connect with their country’s past. But the unpredictable nature of film festivals has left younger generation of Iraqis without faith in the continuance of these creative annual events. Boskovitch remarks that it is imperative to uphold the not just the culture of film festivals but art in all contexts in order to preserve the history of Iraq and foster a welcoming environment for the next generation of artists.

Editor’s Note: Different news sources spell al-Ali’s name differently: Suad, Soad, and Souad.

[hr]

Sung Jung (John) Kim is a first-year in Pauli Murray College. You can contact him at at sungjung.kim@yale.edu.