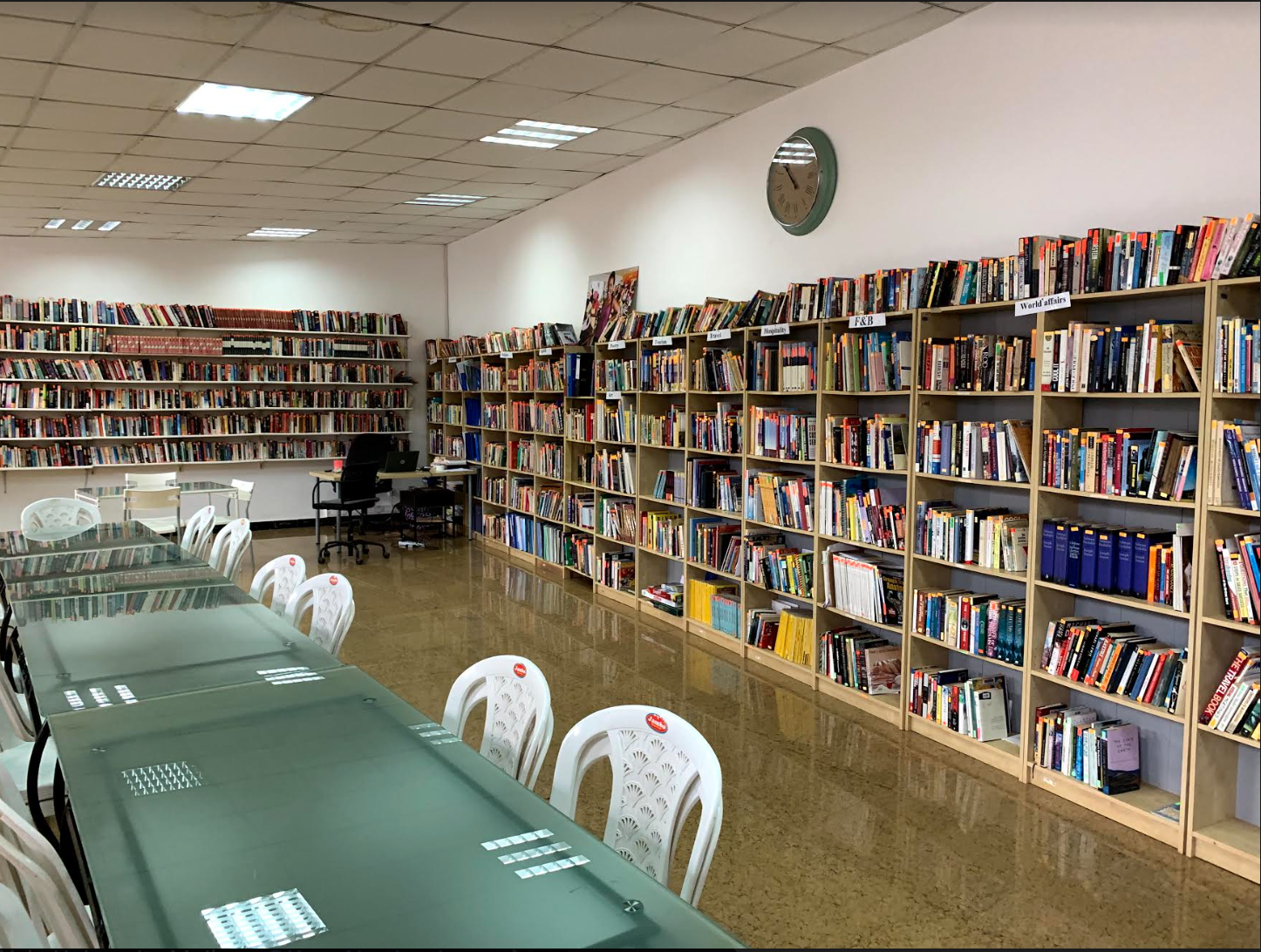

Featured image: The library of Akilah Institute.

By Grace Chen

The walls of Akilah Institute are plastered with signs reminding their students to use English. The acclaimed women’s school aims to address the gap between Rwanda’s current university curricula and private sector hiring criteria; through programs in Information Systems, Hospitality Management, and Business Management & Entrepreneurship, graduates are led to unparalleled success in career placement, especially in industries where they are currently underrepresented. “The pain you feel today will be the strength you feel tomorrow,” one sign reads, “Please speak English on campus.”

The cafeteria is a sunlit room with long wooden tables. White fabric lamps, hung from the ceiling, adorn each corner. Neat brick paths lead the way to Akilah’s classrooms and library, a single rectangular room bordered by bookcases labeled with laminated paper, from Poetry to Food & Beverage and World Affairs. Three students in the Hospitality Management program have agreed to meet with us there between classes. Divine, in a deep blue dress with pleated trumpet sleeves, tells us about the tour company she founded and now leads with five other students. Fida, whose hair is pulled into a tight ponytail, lists club after club when we ask about her extracurricular commitments. She exudes youthfulness, and she struggles to remember everything as she counts on her fingers, ticking off book club, debate, then dance. Yassina tells us about how she sleeps from one to five in the morning to balance school with her responsibilities of caring for her younger siblings.

What they share is their energy for life and learning. Clearly comfortable with English, they share freely with us their experiences as young Rwandan women in school. In return, we offer similarities and differences in what we enjoy and grieve as students ourselves.

“If you are caught using your phone in class, they take it for week,” Yassina tells us.

“A week?” we respond, not able to fathom the outcry that would ensue if the same practice were to be implemented on our own campus. We all shake our heads, Rwandans and Americans alike, for a moment imagining a week without social media.

Our conversation with Divine, Fida and Yassina stands in stark contrast to the interview I attend later that afternoon. Another Globalist journalist and I head to the College of Science and Technology at the University of Rwanda to interview Selman, a third-year math student. Our walk from Akilah to the College is messy; instructions in broken English through WhatsApp lead us from one side of campus to the other, but we eventually find ourselves in the right place. Selman guides us up a wide flight of stairs into a classroom where other students have gathered between classes as well. For a moment I feel like a caged animal in a zoo—all eyes turn to us, this odd trio, and I am reminded of the last time I felt this way a few days prior when I stepped off a bus in rural Butaro, three hours north from the city center of Kigali.

The College of Science and Technology at the University of Rwanda.

Wordlessly, Selman moves three desks together near the back of the classroom and we begin our conversation. It does not take long for us to realize the difficulty in our verbal communication. We turn to writing questions out on paper for Selman to read and respond to, sometimes in written, sometimes in a soft voice I strain to hear.

What classes are you taking?, my colleague scrawls in a notebook.

Stochastic processes, Selman responds, partial differential equations, inferential statistics.

Later, I reflect on how Akilah, a highly selective private institution that seems to serve a much different demographic than the University of Rwanda, the only public university in the country, requires students to pass an English proficiency exam before matriculation. In recent decades, Rwanda’s national language of Kinyarwanda has been joined by French and English. Proficiency in these Western languages have become an indication of socioeconomic status and education level, and while the official medium of education became English in 2008, it seems that implementation has been inconsistent.

Our last evening in Kigali, the team stops by Pili Pili, a restaurant named after an African chili pepper. The sun had already set, but the restaurant, outdoors on a hill overlooking Kigali, is illuminated gently by colored lamps and a pool with underwater lights that change color by the second. Two luminescent beach balls transition between deep magenta and cool turquoise, and a live band plays from the pool deck. A couple of us discover a soccer pitch at the opposite end of the seating area, and a trio of young men welcome us with smiles. They gesture for us to enter through the netted gate in the corner, which we dip our heads to pass under. Pointing to their chests, then to ours, then back and forth, they indicate—let’s scrimmage! Not a soccer player myself, my reflexes are slow, and I stumble over both my feet and theirs. But, through emphatic gestures and hearty laughs that forgo the need for a common language, we enjoy each other’s company, stomachs anticipating our imminent meal.

Grace Chen is a junior in Berkeley College. You can contact her at grace.chen@yale.edu.