By Yuval Ben-David

I’m reading a sleek, cool book right now called The Flamethrowers, by a NYC art critic-turned-LA novelist named Rachel Kushner. The NYTimes did a puff-piece on her a few months ago, about how she rides motorcycles and wears leather jackets. So does the protagonist of her novel, a late 60s filmmaker who accidentally joins the Italian Red Brigades (slick if not sleek, and cool). The slump after finals period also got me re-hooked on Mad Men—plus I’m lying poolside right now listening to the Rolling Stones—so, in classic Yale fashion I’ve transvalued all this consumption into nerdiness and preregistered for a seminar on “The Global 1960s.” I can’t wait to write a paper on hippies.

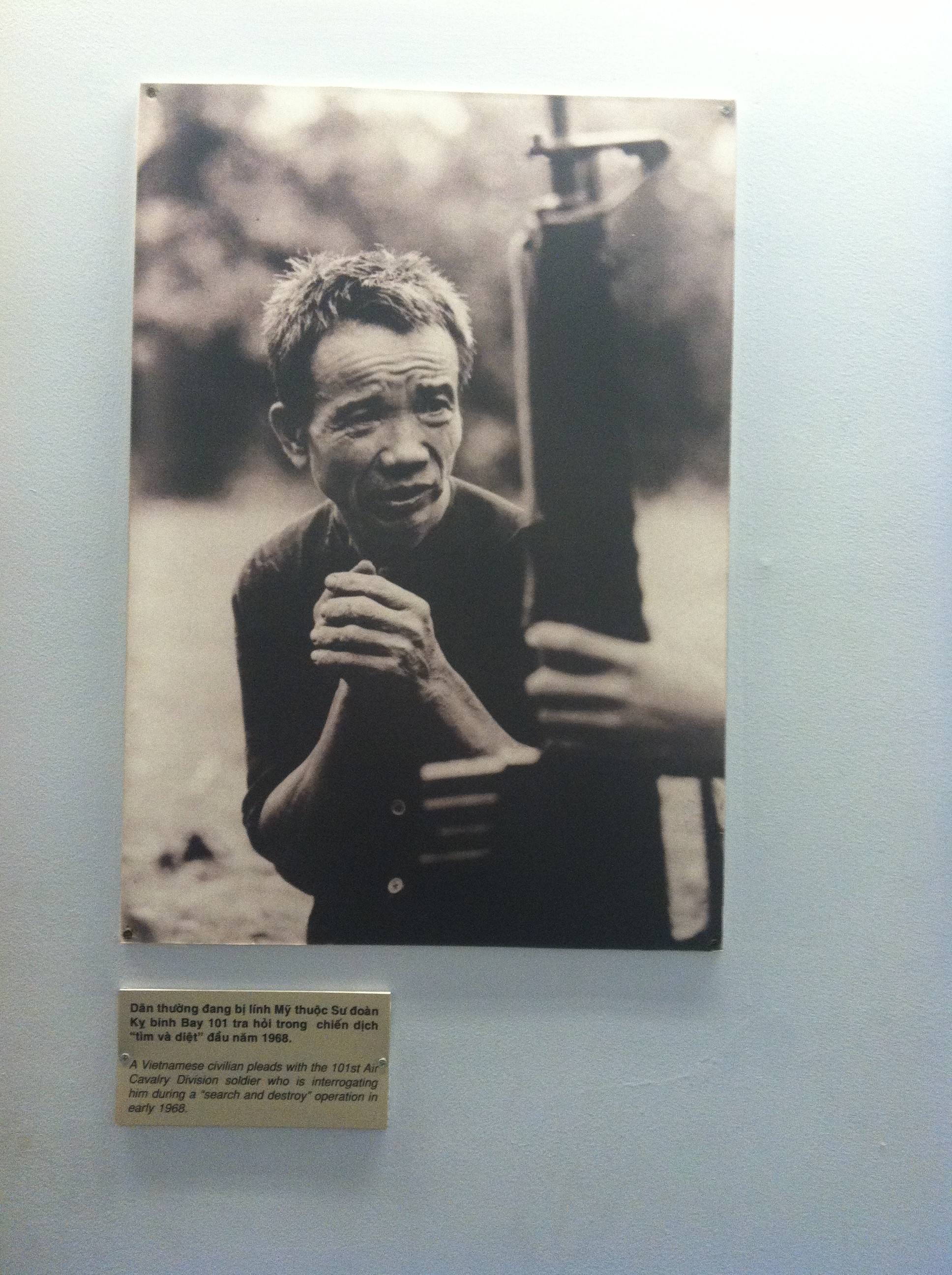

All this is to preface the epiphany I had yesterday about the US invasion of Iraq, about how Bush smuggled it past our collective memory. Bear with me here, okay? I was sitting on a bench outside a display on Agent Orange victims at the War Remnants Museum here in Ho Chi Minh City. Agent Orange was an herbicide cocktail the American military used to deforest Vietnam in order to make bush-cover difficult for the bush-cover-savvy Viet Cong. Decades later, the herbicides’ runoff effects continue to cause birth defects among successive Vietnamese generations—something the War Remnants museum documents with an explicit (and very, very extensive) photo gallery. The local ideologues may believe history is first tragedy, then farce, but the history of Agent Orange is an enduring history of tragedy. Google it. Maybe at first glance the limb-less, tumored victims will strike you as biology’s farce.

I remembered that scene in another of my favorite Sixties historical dramas, The Baader-Meinhof Complex, when a single mother gets radicalized by the TV images of US planes dropping napalm on Vietnam. And I thought about how she stole the history of the Sixties. She became a hippie—and, mind you, a leftie terrorist—because of Vietnam, but all we remember of the Sixties is her and the group sex she had at the hippie commune. The legacy of cool obscures the darker legacy of the Vietnam War.

For my generation, the analogies of the Iraq Invasion to Vietnam said more about the protestors than the war. We thought of them as aging hippies. Our exposure to their caution was secondhand, modulated through the commercialization of the New Left as an Urban Outfitters advertisement. We inherited fewer images of napalm fires or Agent Orange victims. And so, we couldn’t run the algorithm from there to Abu Ghraib. The TV broadcast flickered.

We lost the victims amidst their so-called defenders.

I’ve long held to the view that museums should curate knowledge, not politics. A museum, like a history book, should give the complete and honest account of the world, as opposed to some ideological corrective. Museums and memorials are mutually exclusive, locked in their semantic boxes, I’ve argued. The War Remnants Museum proved me wrong on that point: it’s both. Maybe some would call it propaganda—a one-sided take on the Vietnam War. And maybe I’m just immune to that, because I believe America’s ultimately a force for good in the world; it’ll take more than these photos to change my politics. But the War Remnants Museum sensitized me to the reaches and consequences of American power. It’s a touching memorial and, as a museum, a call to remember. A constellation of truth that pinpricks.

Yuval Ben-David is a junior in Silliman College. You can contact him at yuval.ben-david@yale.edu.